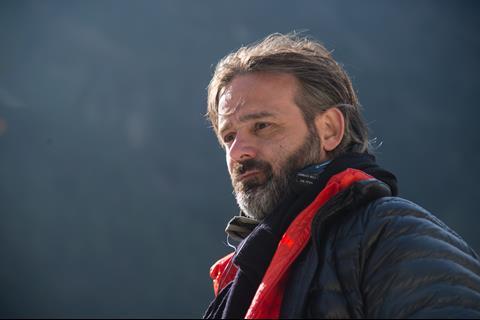

Director Baltasar Kormakur and Working Title co-chair Tim Bevan reveal the remarkable journey behind the Venice-opener.

During the Atlantic Ocean shoot of acclaimed 2012 survival story The Deep, director Baltasar Kormakur contended with treacherous waves, capsizes and underwater shoots in freezing conditions. He even performed stunts.

“That was only half the challenge of this,” laughs Kormakur in reference to Everest, which opens the Venice Film Festival today (Sept 2).

Working Title’s $60m adventure-thriller, written by Gladiator and Les Miserables screenwriter Bill Nicholson and backed by Universal, Cross Creek and Walden Media, was 15 years in the making and posed unprecedented challenges to director, cast and producers alike.

Jake Gyllenhaal, Jason Clarke, Josh Brolin, John Hawkes, Robin Wright, Michael Kelly, Sam Worthington, Keira Knightley and Emily Watson star in the 3D feature based on the real events surrounding the 1996 Mount Everest disaster, in which two expedition groups were caught in a deadly storm on the world’s highest mountain.

Foothold

Development on Everest began soon after the 1996 tragedy.

“Shortly after the incident I discovered that Universal had bought up various rights, and they’d actually developed scripts,” says Working Title co-chair Tim Bevan.

“But then they didn’t want to pursue it. So Working Title, being part of Universal, took that script and those rights over.”

In something of a surprise attachment, Billy Elliott director Stephen Daldry was set to direct the blockbuster in the mid-2000s, even taking a team to Everest Base Camp to shoot footage.

However, when Daldry moved on the project went dormant.

The film’s future became uncertain until four years ago when it found new life in the shape of Icelander Kormakur, with whom Working Title collaborated on 2012 action-thriller Contraband.

In many ways Kormakur was a natural fit. Beyond his impressive body of work, including sharply observed family dramas and survival story The Deep, the director is known for testing himself in the wilds.

Kormakur’s extra-curricular adventures include spartan horseback treks across the highlands and volcanoes of his native Iceland.

“Traveling for three weeks, sometimes fourteen hours a day, unravels you,” says the director of his Nordic expeditions.

“It gives you a chance to better understand who you are. There is a similarity to what some of the mountaineers do. People think you’re crazy for spending your vacation doing it but it’s about getting to your core, seeing what you’re made of and better understanding those you are traveling with.”

Rival

Yet while Everest had seemingly found its perfect match in Kormakur, in 2013 the production’s biggest hurdles lay ahead.

Working Title and Universal were at the time locked in a race with a rival Everest production set up at Sony, which had The Bourne Identity’s Doug Liman on board to direct.

“We knew the Doug Liman script was out there,” says Bevan. “We also pretty much knew what its content was but I always felt confident that the films were quite different.

“Of course I was relieved that their film didn’t get started,” he admits. “You knew that whoever got started first was going to be the one who stood the best chance of getting made.”

Everest was nudging ahead of its rival but was still proving difficult to finance at a budget of $100m+.

“It was hard to finance because it was dramatic, real and didn’t necessarily have a happy ending,” admits Kormakur.

In the current studio climate where sequels and superhero movies rule, mid-range studio films about tragic real life events aren’t necessarily top of the agenda.

“It’s difficult to get a more artistic, for want of a better word, film made inside the studio system,” explains Bevan. “You always have to cobble them together a bit. And we cobbled this one”.

Talent was seemingly never an issue with an impressive number of top actors keen to work on the project.

But changes to the budget meant that co-financier Emmett/Furla Films exited the project in 2013.

Suitors weren’t far away, however. Brian Oliver’s Cross Creek Pictures and Frank Smith’s Walden Media swooped in to save the picture at a budget of around $60m, with Universal remaining the film’s cornerstone.

“Universal were very supportive,” explains Bevan. “They pre-bought all the foreign rights and also guaranteed distribution in America, so we just needed to find the money to fill the gap.”

After “many adventures along the way”, during which time Working Title “got itself into some risky places” [the amount invested in development proved a particular concern, admits Bevan], the money was finally in place.

All that remained now was to make the film…

Recording tragedy

Kormakur and Bevan are both keen to impress the importance of the emotional journey at the heart of their visual spectacular.

For them, the films is as much about personal tragedy, heroism and the results of hubris and human error as it is about spectacle.

With that in mind, the time spent with the families of those implicated in the fateful 1996 expeditions was crucial in powering the film’s heart.

During pre-production Baltasar flew to New Zealand to meet the wife of guide Rob Hall and listen to original radio conversations between the two as he was dying on the top of the mountain.

“Some of those people with whom we listened to the recordings hadn’t listened to them for 18 years,” says the director.

“It was incredibly moving and revealing.”

Kormakur was accompanied by New Zealand actor Jason Clarke, who plays Hall in the film.

“It’s such a powerful thing to have a true story in your hands,” admits Kormakur. “There was a lot of confusion up on the mountain on those days. Errors were made.”

The competing narratives about what happened on the mountain – multiple books have been written about the climb - meant close collaboration with the production’s legal team was paramount.

Cliffhanger

The shoot itself represented the biggest minefield, encompassing Everest, the Dolomites in Italy, Pinewood in the UK and Rome’s Cinecitta Studios.

The nerve-wracking arrival at notorious Tenzing-Hillary Airport in Nepal set the tone.

Known as the world’s most dangerous airport, ‘Lukla’ has no control tower, radar or navigation, and a 9,000 foot drop at the end of an uneven runway a tenth of standard length.

“It’s a cliffhanger,” says Kormakur. “A helicopter crashed there while we were doing our scout.”

Once on ‘dry’ land, fog delayed the team’s ascent to Base Camp.

“The actors had to carry their own stuff and some equipment,” says Kormakur.

Competing shooting schedules meant that some didn’t have time to acclimatise and altitude sickness kicked in close to the 5,000 metre mark. A handful of the party had to be evacuated.

The high-risk conditions and the number of A-list stars involved inevitably gave the film’s insurers the jitters, but the production captured what it needed.

A second unit continued to shoot on Everest while the main production moved to the Dolomites.

Unravelled

Despite the lower altitude, shooting at 3-4,000 metres in the Italian mountains proved less than forgiving.

“At 7am on the first day it was -30 degrees celsius,” recalls Kormakur. “It stayed pretty much like that for most of the six-week shoot. The wind chill was terrible.”

The director was on a mission to unravel his actors in order to capture the physical hardship of extreme mountaineering.

“No acting”, he would say. “’Unravel and be’, was my goal.”

“I don’t believe in the old way of stunts,” he says. “I think the audience feels it. Most of the actors were up for doing their own.”

He singles out Jason Clarke, Jake Gyllenhaal and Josh Brolin as those most eager to go the extra mile.

“They were all prepared to put themselves on the line. Josh was bruised from the knee up after one ladder scene”.

But the whole cast impressed him.

“The actors were in dangerous situations, they had taken pay cuts, and they weren’t in conditions they were used to,” says the filmmaker.

“When you’re out on a remote mountain in -30 degrees celsius with 6 movies stars on a rope and they don’t have a line for the whole day, they’re not used to that. That’s a challenge.”

“A lot of the people – the actors and crew - were afraid they might not be able to pull it through.”

But the tough conditions also built camaraderie, as it often does in real mountaineering groups.

“There were a couple of breakdowns on the way but it also bonded people together. People unravelled in the way I wanted them to.”

And the actors weren’t the only ones to unravel.

“When I came down off those mountains my wife said she’d never seen me like that,” concedes the director.

In Everest, wild man Kormakur had finally met his match.

No comments yet