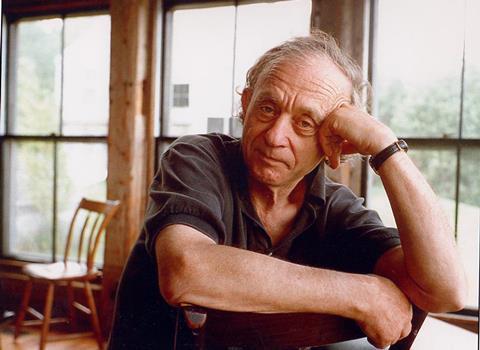

Boston-based 84-year-old Frederick Wiseman, who will be honoured with a Lifetime Achievement Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival tonight (Aug 29) is one of the greatest living documentary makers – and one of the most unobtrusive.

Whether he is tackling films about boxing gyms, ballet companies, strip clubs, universities or hospitals for the criminally insane, Wiseman has the knack of squirreling his way into the heart of institutions. When he recently made a documentary about London’s National Gallery (sold by Doc And Film), he was able to shoot everything from fiery and fraught board meetings to guided tours without anyone seemingly noticing that he was even there.

How on earth does Wiseman persuade big and secretive public organisations to open up to him?

“The real answer to your question is that I don’t know,” Wiseman admits, speaking on the eve of the festival. He always asks for permission first. Once this has been granted, he becomes such a familiar presence that no-one thinks it is odd that he is there. Naked dancers from the Crazy Horse in Paris seem as comfortable with his presence as do museum directors like the National Gallery’s Nicholas Penny.

“Part of it has to do with the way I present myself, whether they trust me or not,” the veteran director reflects on his relationship with his subjects.

“I try to be extremely straightforward, no bullshit. I respond directly to any questions that are asked. I don’t make up any phoney baloney stories. I make my other films available if anyone wants to see them…the general assumption is that other people’s bullshit meter is just as good as mine. If they sense they are being conned, they will either say ‘no’ or be always on the alert.”

Once he is allowed in, Wiseman knows that the subjects will soon relax and stop playing up for the camera. “None of us are good enough actors to suddenly change our behaviour. If we don’t want our picture taken, we say no and walk away. But if we agree, we go about our business.”

In a Wiseman film, not much is provided in the way of context of background information. There are no talking heads or intertitles to explain what is going on. Instead, we are plunged straight into the daily routine of whatever organization he happens to be documenting.

When he made his 2009 film La Danse, about the Paris Opera Ballet, some grumbled that he didn’t identify any of the ballerinas he was showing rehearsing.

“I wouldn’t know where to start!” he states. Yes, he could have identified Nicholas Penny as Director of the National Gallery but, he wonders, does that he mean he has name every other character he shows on screen?

Wiseman films don’t come together during shooting. Their structure is only really discovered during the exhaustive editing process. He will typically shoot hundreds of hours of footage and then winnow it down to feature length, which in Wiseman’s case will normally mean anything from two to six hours.

In his mid-80s, Wiseman’s energy is undiminished. He has new projects on the boil. He has already finished shooting his next film, In Jackson Heights, about life in a multi-racial suburb of Queens, New York.

A keen athlete, Wiseman can’t play tennis any more because of a hip replacement - he used to be part of an ace doubles team at film festivals with venerable British film critic Derek Malcolm.

He still skis regularly, though. “It is different motions, different muscles, so it (the hip replacement) doesn’t interfere - I still ski three or four weeks a year,” the octogenarian director blithely explains.

As for festivals like Venice, he describes them as the perfect platform on which to showcase his work. “Venice has always been very welcoming to me,” Wiseman reflects.

“Film festivals are extremely important, particularly for independent films…as an independent, I don’t have the means that a big production company would have to launch a film. It’s a terrific way to launch a film!”

![The Brightest SunScreen[Courtesy HKIFF]](https://d1nslcd7m2225b.cloudfront.net/Pictures/274x183/3/5/0/1448350_thebrightestsunscreencourtesyhkiff_312678.jpg)

No comments yet