In an interview made available to Screen, the iconic Oscar-winning production designer, who died earlier this month, recalls working on eight Bond films and with Stanley Kubrick.

Sir Ken Adam has designed some of the most revolutionary and forward-thinking sets in cinema, from the war room in Stanley Kubrick’s Dr Strangelove (1964) to the gigantic volcano of You Only Live Twice (1967), which, at $1m, was the largest and most expensive set ever created at that time.

Born Klaus Hugo Adam in Berlin in 1921, Adam went on to design over 70 films, and worked with Stanley Kubrick twice.

He was Oscar-nominated on five occasions, winning twice for Barry Lyndon and The Madness Of King George. He also won two BAFTAs and received seven nominations.

Adam’s other notable credits include Sodom And Gomorrah, Funeral In Berlin, Chitty Chitty Bang Bang and a total of eight James Bond films including Goldfinger and Moonraker.

Adam passed away this month at the age of 95.

The following is an extract from FILMCRAFT: Production Design, published by Ilex Press, written by Fionnuala Halligan.

“I knew I had a passion when I started out, but I wasn’t sure whether my passion was more for cinema or theatre. But I found a sort of compromise as a designer, not with the first film I did but as I went along, that instead of reproducing reality I found it more interesting to invent my own type of reality. That was provided I could talk the director into it – which sometimes was quite difficult because, as you know, in film everyone has an ego problem and I came in like a steamroller. But eventually it paid off.

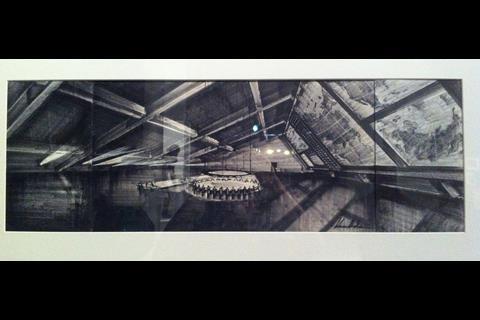

“You see, once I knew the mechanics of designing a decent film, then it became a little boring for me. So I decided to get away from reality – to create an effect which accentuated what the setting had to say.. It really started with Dr Strangelove; years later, when Ronald Reagan became president of the USA he asked his Chief of Staff if could he see the Pentagon War Room, but it didn’t exist, only in the film. I combined a certain amount of theatrical design with real design and I had no reference, it was purely fantasy.

“I remember on the first day I met with Stanley Kubrick, he was talking and I was doodling, scribbling, which is what I liked to do. And I came up with a two-stage or two-level design for the War Room, a little bit like an amphitheatre. And he loved it. So I thought, ‘this is the easiest director I’ve ever worked with! First meeting and he loves my designs’. So I gave them to the art department.

“One day three weeks later he came up to me and said, ‘Ken, gee, what am I going to do with those hundred extras sitting on the second level? I don’t know what they are going to do! I think you’ve got to start again,’ It was quite a shock for me.

“[The final version] took some time because he was standing behind me. And when I came up with that triangular shape he asked me, ‘isn’t the triangle the strongest geometric form?’ I said yes, even though I wasn’t sure, and that sold him. He liked the light frame in the sketch and he decided to light the table with photo floods. So we experimented every evening, standing on chairs, until we got it right. We were very close. But even though we got on well I said to myself after Strangelove that I would never work with him again, such a complicated person.

“And so I got out of doing 2001: A Space Odyssey. But he got me on Barry Lyndon. I didn’t want to do it. He was a very difficult man to work with – extremely talented but on Barry Lyndon I had a sort of nervous breakdown and I said to myself, no film is worth going around the bend for – it’s because we were so close, you know. He was impossible at times and I used to take his guilt onto me, apologizing to actors for something we had done, when I was really apologizing for Stanley. I lost my perspective and so did he. But we remained friends, always.

“He called because he’d seen the sets for Dr No and he loved them, so you could say it all started for me with Dr No and [director] Terence Young . It was the first Bond and it was low-budget stuff and I had nobody who was standing behind me looking over my shoulder – they were all in Jamaica filming.

“I was sitting in Pinewood and I had to fill three stages with sets, so I just went ahead. And they arrived on the Thursday and they had to start filming on the Monday and if they hadn’t liked it, it would have been a disaster. But Terence said he loved it, because nobody had quite done film sets like that before and once I won Terence over, the two producers Cubby [Broccoli] and Harry [Salzman] were on side and then everyone loved it. And that helped me enormously, with my confidence.

“I knew very early that I wanted to be involved in design. When I left Berlin in 1934 I went to St Paul’s school in Hammersmith where I was quite good at drawing and I had a very progressive teacher. My mother kept a boarding house in Hampstead, she had taken the things we had in Berlin, the big tables, the silver, and every night we would have 26 people sitting around one big, enormous table, for dinner, all émigrés, refugees, and I learned more listening to their experiences than I did in any university.

“One was a Hungarian, Gabor Pogany, whose father had designed the original League of Nations building, and he introduced me to Vincent Korda, and through him I decided I would go to the Bartlett [the Bartlett School of Architecture, University College London] in the evenings as an exterior student and I become articled to a firm of architects, CW Glover. I was young, I was 17, but I already fought for my ideas! The junior partner at Glover, a man called Quine-Lay, he pushed me, he was a member of the MARS [Modern Architectural Research Group] group - he said don’t let them shoot you down, keep your ideas.

“Then war broke out, and we were put on air raid shelters. Our district was St Pancras, well you can imagine knocking on the door of every house in St Pancras - I saw things I will never forget my whole life, the way people lived! I got half a crown for every house that I surveyed, although they didn’t like my German accent.

“And I decided at the time of Dunkirk to do something more active in the war against Germany. Because I really hated the Nazis. I first joined a unit for exiles and refugees called The Auxilary Military Pioneer Corps, all the while firing off applications to the Air Force and suddenly my application came through which was a miracle - because nobody else’s did.

“First I went to Scotland, and then to Canada, and then I wangled my way onto an American training scheme called Arnold’s Scheme and started my pilot training in 1942 in Florida. I really started getting interested in films there, because I met John Garfield who was filming Air Force (1943) in Tampa, Florida and he taught me a lot of things. In the end though, in October 1943, I was posted to the top-scoring fighter squadron in the RAF’s 11 Group, the 609 West Riding Squadron, flying Hawker Typhoons. I basically stayed with them until the end of the war.

“Of course, during the war when I came back on leave, my friends in the theatre and films promised me everything – ‘you are the people who are saving us’, and so on. But then when I got out and tried to get work, all I heard was, ‘you’ve got to be a member of the union’. How do I become a member? By working. And I couldn’t work, because I wasn’t a member.

“Just by luck, my sister was working at the American Embassy. And a man came in and said ‘I’m the prop buyer for a film called No Orchids For Miss Blandish (1948) and we need American weaponry, can you help me?’ And she said, yes, I can help you, and I’ve got a younger brother who just came out of the RAF and he would like to get into films. He introduced me to the art director. And that’s how I got into a film studio.

“I did about five or six films before I started working completely on my own and one of the first films where I did a big part on my own [associate art director] was Captain Horatio Hornblower (1951) with Gregory Peck and Virginia Mayo. I found a ship in the South of France and redesigned it as an 18th century frigate and after that I was known as ship expert.

“Jack Warner called me to the island of Ischia near Naples for a film called Crimson Pirate with Burt Lancaster in 1952 and I sailed the big galleon to Ischia and met my wife there. Then I worked in Rome as assistant art director on a film called Helen Of Troy (1956), there were no draftsmen there, so I had to hire architects, and we had a lot of fun, about 14 architects and a brilliant designer called Eddie Carrere.

“I thought I wouldn’t be very long on that film, little did I know we’d be shooting sometimes two units of three thousand extras and they had to be put in costume, weapons and all that – so that was good training for me. Then I started working on my own in England.

“My way of working was to always start with a sketch, even if there wasn’t a script – talking on the phone to somebody, I would be doodling. At that time in architecture the teaching was pretty rigid, so my film designs in the beginning, even though I could make big camera projections, they were to some extent lifeless.

“Eventually I gave up and used a pen called a Flowmaster, a black and white pen with a T-shaped felt nib, and I had a way of controlling it so I could do a very fine line but very strong lines too. So it gave my impression of how the set should be lit, in black and white, and I was known for these rather strong sketches.

“The volcano set for You Only Live Twice was huge. It was the most ambitious interior-exterior set ever built. The dimensions of the volcano were well over 450 feet to the longshot area, which we had tented in, the artificial inclined lake was 120 feet wide, we had a moving heliport flying in actual helicopters, a monorail.

“Once I started designing it I went on and I went on and I went on. I never talked to a cameraman, I just thought, well, somebody can light it. I learned that from Stanley Kubrick, who was also a great photographer, he would never accept from anybody that something couldn’t be done.

“The only option was to get the best cameraman in the world – and that was Freddie Young [Lawrence Of Arabia] – because nobody else wanted to do it. They told me nobody in the world could light it but Freddie looked at the model and said no problem. He got every what we called brute arc, a gigantic arc, in the country, and from across Europe too. And it took every lamp in Pinewood. But he lit it and he lit it well.

“Today you’d do it with CGI and it’s a very effective way of doing a scene but it changes film-making completely. The danger is that directors go crazy. Instead of when they could not get more than 1,000 extras, now they get 100,000 extras with their CGI but it doesn’t look real, the audience knows it’s phoney. So it’s a fantastic new weapon I would say, but it has got to be treated with caution.

“I had so many influences when I was coming up. There were the Russians, Andrej Andrejew who worked for the Korda brothers [on Anna Karenina, amongst others], who was quite brilliant. Then I was very lucky to work on a film with George Wakhevitsch, he was more of an opera designer [for Bartok], but unfortunately it was never made.

“Also the great French art director Alex Trauner, who did Les Enfants du Paradis, and Vincent Koda too, I was lucky to have him as my friend. They were much older than me but there was never any jealousy, they were proud to be with me.

“You had to have a great team with you too, which I developed on each film, I got better and better people behind me, like [visual effects supervisor] Johnny Stears, who always worried about the Bond gadgets, and Ronnie Udell, who was the main construction coordinator, very English and never panicked, always a straight face.

“But it’s not just what you can do or what you can’t do, you have to have the confidence of the people you work with and work for, the director and the producer, and on the Bonds that became more and more important. Mind you, the bigger they became the less critical they were of my work, except for Cubby used to say, ‘every time Ken puts pencil to paper, I have a heart attack’.

“As a production designer, you have to be able to fight for what you want, but you also have to know how to compromise without hurting the film – you can’t do everything. The main thing is that you have the respect and a good relationship with the director and/or the producer, so you’ve got some muscle there, maybe you can get a little more money!

“When a designer has a lot of imagination, well, he is an artist in a way and he is an artist who has to be respected. And I find when I worked on films where I had a great rapport with the director, the cameraman, and if it was a period picture maybe the costume designer too, then the film turned out to be great. If you are all on the same beam, the film will turn out to be a good film, you know – I’ve never been disappointed in that. If you have continuous battles, that reflects eventually.”

![The Brightest SunScreen[Courtesy HKIFF]](https://d1nslcd7m2225b.cloudfront.net/Pictures/274x183/3/5/0/1448350_thebrightestsunscreencourtesyhkiff_312678.jpg)

No comments yet