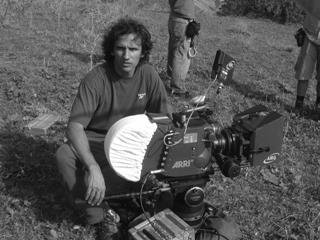

Michelangelo Frammartino talks to Andreas Wiseman about his latest film, Le Quattro Volte.

Michelangelo Frammartino grew up in Milan, where he studied architecture at a local polytechnic. He worked extensively on short films and video installations before releasing his first feature in 2003. The Gift screened at Locarno and picked up awards at various international festivals, including Annecy and Thessaloniki.

His second feature, the bucolic and meditative Le Quattro Volte has impressed at a number of festivals this year. Set in rural Calabria, the film charts the changes to the natural world and the life of a local shepherd across four seasons. The film won the Europa Cinemas Label as Best European Film in the Directors’ Fortnight at Cannes and went on to screen in Karlovy Vary, Toronto, London and most recently in Tokyo. In September Lorber Films snapped up US theatrical rights and New Wave is distributing in the UK in spring 2011.

How did the Le Quattro Volte come together financially?

Well, it was a difficult film to make. It made sense for it to be an international co-production. We had good support from the Torino film lab - $206,253 (€150,000). We also had contributions from other festivals, ARTE Germany, Swiss TV, Medienboad Berlin-Brandenburg, Vivo Films, Ventura Film and the Italian ministry of culture. It was a long and complicated process. The film even came to a halt for a year and a half. From its inception to the screening in Cannes was five years.

Why did you want to tell this story?

There are certain things that always fascinate me. One of those is the relationship between man and his physical surroundings. It’s as though our need to be superior to the things around us has made us lose our communion with those surroundings. I experience this a sort of disease of our times. As a film-maker I’ve felt the need to film not only man and the things around him but that connection between them.

There seems to be a contrast between order and disorder, harmony and chaos in the film…

Yes, as you point out it’s a film that hovers on those borders. I hope that I can say I’m standing on the line between these things. The shepherd himself, besides being integrated into the natural cycle, is also living on that borderline. Historically, shepherds have always been on the edge of society. They are half creature, half man. But if you think of the Gospel they are the ones who announce the birth of Christ. In many religious paintings you see shepherds as existing on that borderline, looking to the sky.

So symbolism and metaphor is central to the film?

I’m not sure. The idea of the symbol is an elaborate one. In semiotics, when it comes to symbolism, you’re already at a developed level of signification. My film is about the first level of signification.

Both The Gift and Le Quattro Volte are shot in Caulonia, Calabria. Why is this area important to you?

Caulonia is the village my whole family is from. I’m the first not to be born there. It has been important to me throughout my life. Perhaps it stems from my interest in contradictory spaces. In Tarkovsky’s films there are often places that exist inside and outside at the same time. In Stalker, for example, there is that room in which it rains. These kind of spaces are common in villages like Caulonia. When I was a child the shepherds would bring their goats into the house. And doors were always open. In Calabria, you enter the room and then ask whether you can come in. And people sit outside with their tables and chairs. In Milan, it’s different: there’s the intercom, the lift, the bell, the spy hole etc. The division between inside and outside is extraordinary.

Did it take long to gain the trust of the goats you observe so closely in the film?

That didn’t take that long, actually. Many of the kids were born while we were there so they were convinced we were part of their surroundings. But I did learn a lot about animal behaviour. If you place a chair in their shed, for example, they will climb it like wild mountain goats climb rocks.

You’ve said before that this is a political film? What do you mean?

In Italy there is a strong connection between images and power. This means that images drive you to think in some way. All images require a choice. If you make a film about shepherds in ancient Calabria the audience is free to decide. The goat is not just a goat, there is something behind it, but you have to imagine what it is and make the connection. Jean-Marie Straub said: ‘I don’t shoot for spectators, I shoot for citizens.’ A citizen is someone who is free to decide. So, making a film that gives you freedom to decide is a political film.

What does the film’s title mean?

It refers to something that Pythagoras is supposed to have said. He lived and taught and developed his ideas about reincarnation in Calabria. He said that each of us has four lives, each of which is enmeshed with the other: man is a mineral because his skeleton is made up of salts and minerals; a plant because his blood is like the sap of plants; an animal because he has memory and movement; and he’s also a rational being. In order to know himself completely man needs to understand these four things.

I read that you are working on an animation project. Will that be your next film?

I never write my films. I draw them. When I draw I get closer to what is in my mind. I did this with the central scenes of Le Quattro Volte. With my latest project I started drawing and then didn’t stop. The Italian generation of the 70s and 80s grew up in a tense and violent time so they withdrew to their homes where they were exposed to new messages through TV and new cultural projects. My next film is the story of a child growing up at home with these images. Somehow he enacts the story of the whole country in his home. The same producers of Le Quattro Volte - Vivo Films, Ventura Film, Essential Filmproduktion, Coproduction Office - are involved. But I would also like to make it at the same time as something else.

![The Brightest SunScreen[Courtesy HKIFF]](https://d1nslcd7m2225b.cloudfront.net/Pictures/274x183/3/5/0/1448350_thebrightestsunscreencourtesyhkiff_312678.jpg)

No comments yet