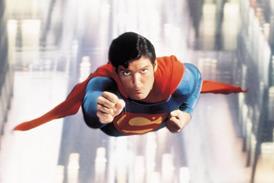

Christopher Nolan’s first film to be anchored in real events is a soaring war epic which impresses on every level

Dir/scr: Christopher Nolan. US/UK, 2017. 108 mins.

A masterful Christopher Nolan flings the viewer into the air, the sea, and that beach for Dunkirk, his tense new navigation of the war film. From script level, which pilots three time frames and strafes his own fiction onto the reality of the Allied evacuation of June 1940, to its astonishing technical prowess, this is heart-stopping entertainment. There may be money on the screen, but cash alone can’t guarantee this kind of pulsating, cinematic magic, delivered by a director at the height of his powers, mustering the very best at their craft.

In the great tradition of the War film, Dunkirk never once lets audiences forget the sacrifices made in their name

Those wondering what a classic War movie might look like today will see something bigger – shot in a mixture of 65mm and Imax – tighter, more propulsive, but the heart and soul of the genre is all there, undiluted by CGI or any directorial self-indulgence. Dunkirk is, like Avatar, a film which demands to be seen on the big screen with the best available sound, a need which should deliver impressive theatrical returns for Warner Bros long into the future. Nolan’s cast of young, unfamiliar British actors backed by heavyweights from Kenneth Branagh to Mark Rylance and, ultimately, Tom Hardy, adds fresh appeal. Pop star Harry Styles – good – won’t hurt prospects.

Ultimately it’s the virtuosity of Dunkirk which so impresses: Nolan’s powerful choreography of his precision piece, using his trusted team of actors and longtime HoDs. Land, sea, air; human flotsam on the vast and terrifying stage of war; three time frames intersecting in Nolan’s favoured jigsaw structure which all but demands repeat viewing.

Hoyte van Hoytema’s lucid camera swivels from tight, fraught interiors to the empty sky and sea vistas; designer Nathan Crowley’s three worlds are distinct yet collide; sharp editing by Lee Smith lends a razor’s edge to the script. And sound: Hans Zimmer’s score picks up on the noise and terror to amplify and enhance, ultimately teasing with Elgar’s Nimrod but never overtly manipulating.

Dunkirk, which details the British withdrawal from the Continent, arrives at a time when that country is sharply divided over another retreat from mainland Europe. That might be a coincidence – the on-location shoot was over by the time of the surprise Brexit vote last year – but Nolan’s film could find itself sucked into the political maelstrom in a UK struggling with what ‘Dunkirk Spirit’ might mean in 2017. Other Allied forces including the French troops - who held the line for the evacuation - have no real part to play here, with one lone exception, and Churchill’s decision to go back for them is also not mentioned. This is a British war film.

Overall, however, Dunkirk will be hailed, and should endure, as classic craftsmanship, the year’s must-see film on the global stage. Even a complete lack of female characters should be forgiven in the face of Nolan’s daring achievement, as his only film to be rooted in reality cements his position in the dream factory.

Over five tense minutes go by before a word of dialogue is spoken: Dunkirk begins and ends with young actor Fionn Whitehead playing an unidentified soldier whom the camera follows onto Dunkirk beach where 400,000 trapped and defeated Allied forces hope for rescue. It’s a breath-taking reveal, yet ideas of Saving Private Ryan or The Longest Day are quickly dissipated as Dunkirk then cleaves into three distinct parts and timelines.

One focuses on the ‘mole’, a week-long operation - supervised by Kenneth Branagh’s admiral - which used the beach and the East Mole (sea wall) to board the troops on rescue craft (Dunkirk’s docks had been destroyed). Part 2 is devoted to “the sea”, a day-long rescue mission (Operation Dynamo) by the “little ships”, British pleasure vessels who answered the call to rescue the soldiers and bring them home across the 26-mile stretch of the English Channel. And the third part, whose timeline is a mere hour, follows two RAF Spitfire pilots as they desperately try to provide cover against the Luftwaffe, who are picking the waiting troops off.

Nolan shoots, cuts and scores these stories together as if he were the conductor of a great orchestra, restructuring and redefining a classical piece. It’s not unusual for his world to pivot and turn upside down (shades of Interstellar, or Inception), the dread shifting from night to day, from fast action to classical tableaux, underwater to overground, to leave the viewer as disorientated as the characters they follow.

His young cast impresses across the board, but particularly young Fionn Whitehead in his first big-screen role. His journey is the emotional heart of the film, as he struggles to survive — opportunistically - with his cohorts played by Styles and Aneurin Barnard. Another newcomer, Tom Glynn-Carney, mans the small vessel Moonstone with Barry Keoghan (The Killing Af A Sacred Deer), for Mark Rylance’s doughty captain and Cillian Murphy’s shell-shocked officer. In the air, Jack Lowden becomes more recognisable as the dogfight with the Luftwaffe progresses. Branagh and Hardy roll out the gravitas for scenes which anchor the youthful energy.

In the great tradition of the War film, Dunkirk never allows audiences forget the sacrifices made in their name. Nolan’s film would be a great technical achievement, but the added element - or magic - of Dunkirk is the onus he places on the audience to think themselves into this fight for survival. Dunkirk uses dialogue sparingly, and any heroic speechifying is pared down to a minimum as this 108 minute film reverberates with the noise and desperation of men at war who scramble for survival, sucking you in.

The notion of a Dunkirk Spirit has been appropriated by those who would see Britan retreat into itself, but Nolan’s film helps make it great again. As he leaves his survivors facing into a dark future, we are reminded of those desperate, noble souls who tried to fight for something pure and hold the line for Europe. That will be a very welcome message indeed in these times.

Production company: Syncopy

Worldwide distribution: Warner Bros Pictures

Producers: Emma Thomas, Christopher Nolan

Executive producer: Jake Myers

Cinematography: Hoyte van Hoytema

Production design: Nathan Crowley

Editor: Lee Smith

Music: Hans Zimmer.

Main cast: Kenneth Branagh, Cillian Murphy, Mark Rylance, Tom Hardy, Fionn Whitehead, Tom Glynn-Carney, Jack Lowden, Harry Styles, Aneurin Barnard, James D’Arcy, Barry Keoghan, with