Dir: Stevan Riley. UK. 2015. 97mins

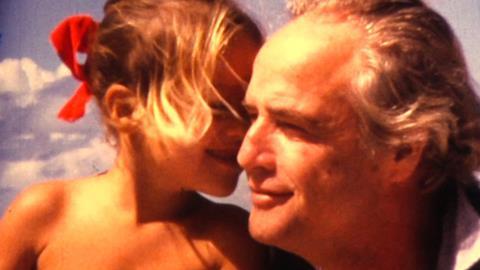

Marlon Brando spent the last decades of his life running from any attention. Yet he had something up his sleeve. In Listen To Me Marlon, we have an unprecedented portrait of the actor, culled from 200 hundreds of hours of recordings that Brando made by and about himself.

Listen To Me Marlon is an elegy, with scenes of extraordinary beauty throughout.

In Stevan Riley’s impressive documentary, we have Brando’s own voice, and an extraordinary visual journey through the actor’s life and work, revealing a complex troubled man. Commissioned by Brando’s estate to mark the tenth anniversary of his death, it connects a distant icon to a voice.

Brando taped himself for decades. With humor and self-doubt, he talks about Shakespeare and Hollywood and boxing, about Civil Rights and American Indian grievances, about the pain of growing up with his parents and the serenity of Tahiti. He can be eloquent and defensive, angry and reflective.

Listen To Me Marlon builds on what Brando put on the tapes, which is a vast amount. Riley brings elegance to the staggering volume of audio testimony, as if this were an essay film inside an auto-biopic. He starts with the childhood and youth, marred by a mother’s alcoholism and a father’s brutality. Again and again, the actor says that he could never put those experiences behind him. Brando’s ticket out of town was the New School for Social Research in New York, and then study with Stella Adler, who stressed self-control in acting. The dutiful Brando mastered the actor’s craft to become one of Adler’s stellar pupils, but he struggled with his appetites, his family and with the business of Hollywood, eventually choosing roles that would enable him to avoid work most of the time.

Brando’s candor here is a revelation. When he says “money, money, money” about the studios, you can’t help hearing echoes in that voice of “oh, the horror,” from Apocalypse Now.

Even with those mounting frustrations, acting was a triumph over his father’s constant disapproval, but not a refuge. When critical praise came, Brando chafed at being branded as a primitive, although he doesn’t use the word. The tapes reveal that the man who played Stanley Kowalski relied on much more than instinct. He also fought with directors much of the time.

Tahiti, which Brando discovered while filming Mutiny On The Bounty, became a serene radiant paradise for a while, and triggered misery after the suicide of his daughter Cheyenne there in 1995. Her boyfriend was shot dead in 1990 by Brando’s son, Christian, who went to prison for the crime. The film makes it clear that Brando was never father of the year.

For all its testimony from Brando, Listen To Me Marlon leaves room for future perspectives on the man. Much of his private life is left unexamined, as the film concentrates on Brando’s own narration, and only a fraction is in the film.

Riley also gives us powerful visual metaphors for those who want to know the man. These moments could stay with you as long as anything that Brando says.

One is the digital rendering of Brando’s head, commissioned by Brando in the 1980’s in ghostly white, which looks like a death mask. Brando, concerned about how others judged him, created his own memorial in this strange effigy, which speaks in his voice from the tapes in the film.

Another recurring image is Brando’s sprawling but deserted house on Mulholland Drive, where Christian shot Cheyenne’s boyfriend, and where the actor himself hid out much of the time. Jack Nicholson bought the property after Brando’s death and demolished it. In the eerily dark interiors that the camera observes, recreated by Riley on a London soundstage, you get the sense of a recluse’s cave, not a home.

An improbable but unforgettable image comes from Brando’s memory of the boxer Jersey Joe Walcott, whose confusing ring style kept opponents off-balance, the better to surprise them with a knockout punch. Brando, who admired Walcott, insists on tape that good actors exploit the element of surprise. Walcott, like Brando, was a smart man relegated to the status of a crude natural talent. Riley also shows Walcott brought down by Rocky Marciano, a true primitive. Like Brando, Walcott was determined, and misunderstood.

Listen To Me Marlon is an elegy, with scenes of extraordinary beauty throughout – not least the young Brando himself — but Riley has not made a hagiography, nor is this documentary just for Brando fans. Most actors are lucky, with a ghostwriter’s help, to produce two hundred pages of gossip. Riley has sifted through mountains of tapes and found the same emotions that made Brando the actor of his generation.

Production companies, backers: Passion Pictures, Showtime, Universal Pictures Home Entertainment Content Group, Brando Enterprises

International sales: Passion Pictures nicoles@passion-pictures.com

Producers: John Battsek, R.J. Cutler, George Chignell

Executive producers: Andrew Ruhemann, Avra Douglas, Mike Medavoy, Larry Dressler, Jeffrey Abrams

Screenplay: Stevan Riley, Peter Ettedgui

Cinematography: Ole Bratt-Birkeland

Production designer: Kristian Milsted

Editor: Stevan Riley