Dir: Ben Rivers. UK 2011. 88mins

A solitary but strangely poetic life is given an intimate, impressionistic treatment in Two Years At Sea, a hand-made, beautifully artisanal black-and-white miniature by Ben Rivers. The British artist/film-maker has enjoyed a breakthrough year in 2011, with his works screened in major London art venues including the Hayward Gallery, and acclaim for his film Slow Action, a visionary evocation of alternative worlds that bears comparison with work by Chris Marker and Peter Greenaway.

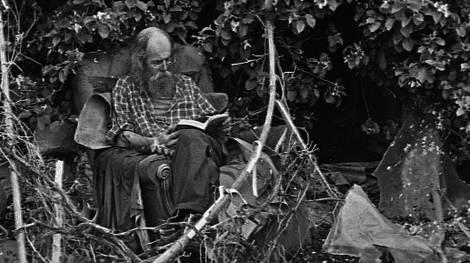

Two Years At Sea revisits an earlier Rivers subject, Jake Williams - a hirsute Tolstoy lookalike presented here as both a dreamer and a muscular man of the land.

Two Years At Sea is in some ways a more conventional piece, but its empathetic portrait of a characterful outsider, and the sheer beauty of its imagery should strike a chord both with Rivers’s gallery following and with festivalgoers, who will appreciate echoes of such outsider portraits as The Moon and the Sledgehammer and Grey Gardens. Adventurous niche distributors could also navigate the film into theatrical waters, given the recent success of similarly impressionistic nature-themed works such as sleep furiously and Le Quattro Volte.

Rivers’ catalogue of shorts includes several free-form portraits of hermits and social outsiders, usually living in rural isolation and pursuing their fascination with archaic, subsistence-level technology. Two Years At Sea revisits an earlier Rivers subject, Jake Williams - a hirsute Tolstoy lookalike presented here as both a dreamer and a muscular man of the land.

Living in heavily forested terrain on the edge of Scotland’s Cairngorm Mountains, Williams inhabits a ramshackle house with a caravan as annex, and the film partly follows him, reportage-style, about his daily life. Williams gives the film-maker very intimate access to his activities, such as taking a shower in his cluttered bathroom cum kitchen.

But there are also fantasy elements at work. One remarkable sequence has Williams, head deep in foliage, drift off into sleep, waking to find that - in a marvelously comic image - his caravan has mysteriously risen up into the treetops. Another key sequence shows him trudging across windblown terrain carrying on his back the pieces of a makeshift boat; lashing it all together, he then drifts off across the still waters of a lake in an extended shot that, one imagines, partly motivates the title of this film about a landlocked existence.

The soundtrack comprises a beautifully esoteric collage of music - Indian ragas, scratchy guitar blues, ribald vintage British folk - that presumably reflects Williams’ own tastes. While there’s no commentary to give us explicit information, occasional photographs - taken, one suspects, by the protagonist himself - offer hints about his former life and, perhaps, family.

The film is shot by Rivers himself in black-and-white 16mm on a Bolex with anamorphic lens, and developed by hand, giving occasional staining effects that are a Rivers trademark. For all the film’s DIY nature, the result is a beautifully hand-made piece of imagery, the outdoor shots achieving a beautiful starkness reminiscent of Bela Tarr’s films (not to mention much 20th-century Hungarian photography), with a delicate capture of textures, whether in forest greenery or in William’s equally lush beard. A magnificent eight-minute closing shot of the hermit lapsing into reverie as he stares into a fire is magnificently haunting, bringing us closer to Williams than ever while reminding us that he’s really unknowable.

Production companies: Arts Council England, Film London Artists’ Moving Image Network, Periferia Filmes

Producers: Maggie Ellis, Rose Cupit, Joao Trabulo

Cinematography: Ben Rivers

Sound: Chew-Li Shewring

Editor: Ben Rivers

Main cast: Jake Williams