Victor Kossakovsky follows up ‘Gunda’ with this exploration of concrete and stone in a throwaway society

Dir: Victor Kossakovsky. Germany/France. 2024. 98mins

If Victor Kossakovsky’s 2018 documentary Aquarela was an essay about climate change told through the medium of water, Architecton turns its attention to our planet’s shell of rock and stone, and its use – or misuse – in the structures we humans build to live, work and pray in.

Some viewers may be frustrated by Kossakovsky’s resolute refusal to tell us where we are

Even before the opening credits have finished rolling, Architecton impresses. The camera flies through a gap ripped out of a Ukrainian residential building, then climbs the gash in the side of another, noting the clothes still hanging in the wardrobe of a room cut in half. We cut to a view of a huge ancient monolith with a weathered surface that looks alive, like elephant skin. Then comes the coup de grace: a rockfall played in slow-motion, in three successive framings: close, medium and long. Huge blocks, set free from their geological sleep, tumble in a liquid flow.

Berlin-based Kossakovsky has a tried and tested ‘show, don’t tell’ method, most recently on display in Gunda, the empathetic 2020 pig’s-eye-view documentary that was released theatrically in a raft of territories. This Berlinale competition entry is not nearly as cute as that EFA-nominated sow biopic, but it is deeply, often ravishingly cinematic, right down to the kind of sound effect rips that we might associate more with disaster movies.

Cinematographer Ben Bernhard, whose deft touch and feel for light illuminated the Oscar-nominated urban nature documentary All That Breathes, brings a tactile sensibility to shots of ruined carved friezes or the sawn gash in the trunk of a felled tree. Evgueni Galperine’s other-worldy music (conceived as a standalone album, ’Theory of Becoming’, in 2022) – sometimes ominous, sometimes ethereal – is the perfect match to Kossakovsky’s clarion call.

The Russian-born director’s thesis, propounded in the connections it forces the audience to make between its captionless, comment-free scenes, is that we are living in an age of shoddily built structures designed to last, at most, half a century. A sequence towards the end even shows an entire city district being demolished.

Architecton features the Italian architect, designer and theorist Michele De Lucchi. With his shaggy beard and round architect’s glasses, De Lucchi is neither narrator or guide; in fact, he takes on more of a spiritual role. Interleaved with the scenes of rock being processed, ancient ruined temples and unfinished Brutalist edifices, the camera switches to what is presumably is De Lucchi’s country house near Milan. Under his watchful eye, a local mason and his assistant are making a stone circle in his garden. We understand its purpose only right at the end, when the director breaks his ‘no-narrative-explanation’ rule to appear in his own film, gently interrogating De Lucchi in that same garden, teasing out of him a mea culpa for being a part of the ‘throwaway architecture’ problem while he gropes towards a solution.

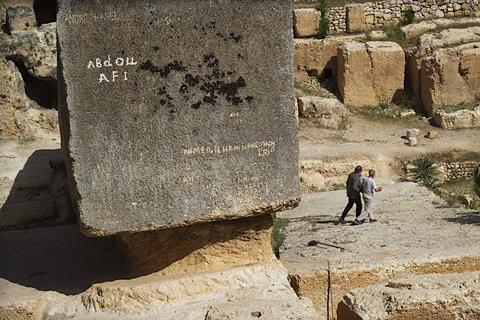

Some viewers may be frustrated by Kossakovsky’s resolute refusal to tell us where we are. Only one great monument is identified, the Roman site of Baalbek in Lebanon, when De Lucchi gets chatting to Abdul, the self-appointed cleaner-up of the ancient quarry that lies a couple of miles away. And there is a thornier issue that is left unsaid, because it would disrupt the clean, linear power of Kossakovsky’s contention: concrete is not a modern invention. One of the greatest surviving edifices of the ancient world, Rome’s Pantheon, has a concrete dome.

Mostly, though, the director makes a compelling argument. And the main thing with a rousing cinematic experience like Architecton is that it wins the emotional argument.

Production companies: Ma.ja.de. Filmproduktions

International sales: The Match Factory, info@matchfactory.de

Producer: Heino Deckert

Editing: Ainara Vera

Cinematography: Ben Bernhard

Music: Evgueni Galperine

![The Brightest SunScreen[Courtesy HKIFF]](https://d1nslcd7m2225b.cloudfront.net/Pictures/274x183/3/5/0/1448350_thebrightestsunscreencourtesyhkiff_312678.jpg)