Director Bennett Miller and producer Jon Kilik reveal why Foxcatcher - their murderous story of class, power and brotherly love - was so many years in the making. Jeremy Kay reports.

When Foxcatcher dropped out of its much-anticipated world premiere at AFI Fest in November 2013, many feared Bennett Miller’s new film might be the turkey that was ducking out of Thanksgiving. The bombshell had come the day after Sony Pictures Classics (SPC) announced it was yanking the drama from the 2013 awards season and was shifting the US release from the end of that year to some time in 2014.

The film had already endured a lengthy post-production schedule and now there was this - the delayed release and cancelled premiere scenario that can so often indicate stormy weather on a film’s horizon.

To the inner circle of Miller, fellow producers Jon Kilik, Anthony Bregman and Megan Ellison as well as SPC, however, the story was quite different.

“This is a movie that’s a meticulous work,” says Kilik. “Megan and I wanted to support Bennett fully and all three of us felt it wasn’t exactly perfect and knew we had some things to uncover and needed a couple more months.”

‘The wrestling community is a small and insular group, and this is a dark chapter in the history of the sport’

Bennett Miller, director

Foxcatcher had already endured a tortuous development cycle and a taxing search for funding, so the film-makers were not going to let an extended period of post-production stand between them and a great final version.

Ellison, whose Annapurna Pictures co-financed the film with Sony, agreed to bankroll extra time in the editing suite. It was worth the wait. One year after Foxcatcher was pulled from AFI Fest, it returned to close the 2014 edition.

By now it was an acclaimed commodity following Miller’s best-director prize in Cannes, where Foxcatcher had received its world premiere, and subsequent sellout shows at Telluride and Toronto. The Los Angeles homecoming tied a neat, karmic bow around the whole episode. Weeks later, Foxcatcher would score a spectacular limited opening weekend in the US. Miller’s latest feature, which opens internationally in early 2015, was firmly on the map.

Oddball appeal

Rewind eight years and Foxcatcher was a mere speck of an idea in the film-maker’s mind. It had been several months since Miller’s directorial debut Capote had garnered five Oscar nominations, including one for best director and a famous best actor win for Philip Seymour Hoffman.

The new prince of Hollywood was wondering what to do next and, by the time he sat down for an introductory meeting with Kilik that autumn, he had begun mulling over the unsettling real-life events that would inform Foxcatcher.

It was a stranger who had alerted Miller to the story of John du Pont. Always fascinated by driven, eccentric outsiders, the film-maker became obsessed with the case of the heir to a chemicals fortune. Miller researched how the wealthy misfit set up a training camp for the US wrestling team on his Foxcatcher estate in Pennsylvania, bringing into the fold Olympic world champion brothers Mark and Dave Schultz. An intense relationship would develop between the three men, resulting in du Pont eventually shooting Dave dead.

“I had an image of this guy [du Pont] in a wrestling room, watching wrestlers practise,” says Miller. “In my head it was an image of this guy watching these guys and knowing that he doesn’t belong there and they’re aware of him watching them and they don’t quite belong there, either.”

He added: “If you want to know the beginning, it was that - bang - and the fact that it ended tragically.”

Miller had already acquired Mark Schultz’s life rights when he met Kilik, the Oscar-nominated Babel producer whose collaborator on that film, Media Rights Capital (MRC), had orchestrated the meeting. MRC agreed to fund development of Foxcatcher and the film-makers got going. E Max Frye came on board to write a first draft before Miller’s Capote collaborator, Dan Futterman, became involved.

Tall order

“It was a long road and a tough movie to figure out the storytelling of it,” says Kilik. “It was tough to finance. Any time you’re trying to force into existence your own material, especially as the independent market has been shrinking over the last decade or so, it’s harder and harder.

“The producer or first partner is the one that confirms you’re not crazy, it’s worthy, it’s going to be great. I was that person for him - to keep his hopes alive.”

Miller remembers that by 2008 he was ready to move ahead but, for one reason or another, MRC was not and the process hit a roadblock.

“Reality set in and eventually I had to concede that it wasn’t going to happen,” says Miller. “I put it down and made some changes in my life, my representation, and stuck a pin in it.”

A temporary pin, as it transpired. Neither Miller nor Kilik had any intention of letting Foxcatcher die - although it has to be said their ‘stop-gap’ projects take some beating. Miller made Moneyball, which would earn six Oscar nominations and more than $110m at the worldwide box office. And Kilik? “I went off and did The Hunger Games.”

The director resumes the film’s story. “When Moneyball was winding down, John du Pont died in prison in December 2010. I always intended to return to [Foxcatcher], and that was the catalyst.” It turns out interim activities had only served to fuel Miller’s view of the project’s potential.

“The more I looked at it, the more it revealed itself and the more I reflected… the challenge and intrigue of it was captivating. Once I start something, it’s very, very hard to let go.”

The film-makers struck gold when Miller met Ellison in spring 2011 and pitched Foxcatcher. “She just said, ‘I would love to make this film with you.’ Then we embarked on this long process,” Miller recalls.

“Megan is single-handedly changing the face of independent production with her great taste and commitment to the exact type of situation where you have an auteur director with a strong taste for something,” says Kilik.

“She helps to not just provide the money but is there until you find distribution, so she’s able to make the commitment and not have it be conditional, in the way it often is with other investors.”

Miller says of Ellison’s involvement: “I can say that was a big measure of confidence, because I had spent so much time trying to find the money and a partner who could feel similarly about it.”

Both Miller and Kilik cite Ellison as a driving force in arguing to pull out of AFI Fest 2013 at a time when the film-makers agreed showing it would have been a disservice to the film.

“To me, that’s the mark of a producer,” says Miller. “In the moment when the film-maker could be expected to be making that case and lobbying against the push-back of a producer, it was she who led that.”

Ellison’s relationship with Sony meant that Miller was once again circling in the studio’s orbit. At first, Columbia Pictures was set to distribute, as it had done on Moneyball. Eventually the film landed at Miller’s Capote collaborator, SPC.

Foxcatcher began production in West Pennsylvania in October 2012 and wrapped in spring 2013, teeing up a prolonged period of post.

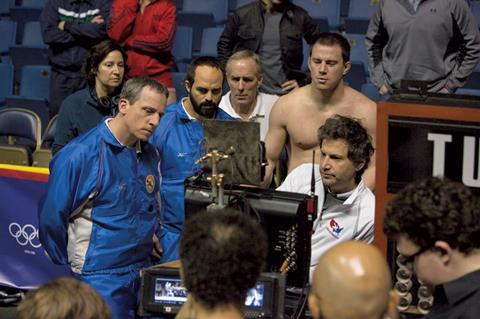

The results vindicated the process, with critics and festival programmers showering praise, in particular on the broadly leftfield casting of the three leads. Mark Ruffalo is terrific as the doomed Dave Schultz and is perhaps a more obvious selection given the actor’s own credentials as a former state wrestling champion.

As casting goes, the decision to go with Channing Tatum as Mark Schultz and Steve Carell as du Pont was out-of-the-box genius.

The former shows hitherto unseen depths while Carell, almost unrecognisable with a prosthetic nose and dead eyes, taps into a dark side few knew he possessed. Miller had wanted Tatum from the start after he watched the young actor in 2006 drama A Guide To Recognizing Your Saints.

“It was about eight years ago and I met him to discuss Foxcatcher and this role before I even had a script,” the film-maker recalls. “The fact that he existed was some incentive to make this film, because I knew there was an actor who could do it.”

Tatum’s career has soared since 2006 and taken a distinctly populist turn, yet Miller was undeterred. “The lighter stuff he had done was sort of beside the point; I was sold at Saints.”

‘The producer or first partner is the one that confirms you’re not crazy. I was that person for Bennett Miller, to keep his hopes alive’

Jon Kilik, producer

“If you know Mark Schultz as I do,” says Kilik, “Channing got every nuance. Same with Ruffalo.”

Miller had tried to cast Ruffalo as Perry Smith in Capote but, try as he might, the actor turned him down three times.

“I was befuddled by this strange twist of fate whereby I was making another film where I didn’t see an alternative to Mark in this role and I was putting myself in a position to be rejected by him again.”

This time Ruffalo was in. He had wrestled to a very high level - like his father - and had lost a brother. The pull was too strong.

Carell’s name featured on a list from an agency but did not rise to the top straight away. “It was really only over time that the notion began to sink in that it made a bizarre counter-intuitive sense,” says the director. “Carell said to me he had only ever played characters with a mushy centre. Du Pont seems to have a mushy centre but he doesn’t. It revealed an understanding of a character who can possess a public persona and conceal a private truth about their danger.

“I often feel this way about comic actors - they do have a guarded side to them, a darker side, a sharper side that’s a contradiction to their public persona. I’ve always thought Carell was a very good actor, perhaps under-appreciated because of the benign banality of these characters that he likes to play. As it often is with comedic actors, he was very specific and very refined, and he listens as a comedic actor really has to listen.”

“It just made Bennett think,” says Kilik of the early inclusion of Carell on that agency list. “The element of surprise was important and what Steve did on every level is amazing. All three of them were equally brilliant.”

Tatum and Ruffalo trained for seven months under the tutelage of Dave Schultz’s good friend, John Giura. Tatum is a natural athlete but still had to work hard to grasp the moves and form of wrestling.

“They were using weights and learning the moves,” says Kilik. “Mark Schultz was known for his lats [back muscles] and Channing spent a long time in the weight room expanding that size. These are details nobody would know about, watching the movie.”

Ruffalo brought his own wrestling experience, although as a right-hander he went for authenticity, working to grapple in the exact manner of his ‘lefty’ character, renowned as one of the all-time greats.

Crucially, the production had early support from Nancy Schultz, Dave’s widow, played in the film by Sienna Miller.

“That relationship began maybe five or six years before we began shooting, so by the time we started shooting I knew her quite well,” says the director. “In the beginning she was amazingly generous and non-judgmental. She wanted to know what we were doing, but not disrespectfully. She felt she had the right to know.”

Inner circle

It was Nancy Schultz who introduced the film-makers to people in the world of Foxcatcher and the wider sport beyond that.

“The wrestling community is a pretty small and insular group, and this is a dark chapter in the history of the sport and many of Dave’s close friends are big figures in the world,” says Miller. “It was the credibility that Nancy gave to the project that enabled these relationships to take root.

Before the shoot began, she gave Ruffalo a pair of Dave’s glasses to wear in the film. A small gesture like that brings it home - he’s wearing glasses that Dave’s widow gave to him.”

The death of Dave Schultz devastated the world of wrestling and all who knew him. Yet the trajectory of Mark, who cuts a sombre, downtrodden figure throughout most of the film and ends up cage- fighting, is heartbreaking.

“It is the whole concept of the broken American promise,” says Kilik. “You work hard and put in what it takes to represent your country and go home with a gold medal, and you’re an assistant part-time gym coach who can barely make ends meet. You’re almost like a soldier who comes home after risking his life and you’re an outcast.”

Kilik points to Foxcatcher’s broader themes, too. “It’s America, it’s class, it’s power, societal issues. You wonder how could these two guys [Mark Schultz and John du Pont] inhabit the same country. It’s pretty amazing.”

Another theme of Foxcatcher is the continued march of Bennett Miller as a major US auteur of consistently captivating work. Audiences quite rightly are fixating on the performances of the three leads, but Kilik is keen that the creative guiding light not be overlooked.

“What’s so brilliant about the way Bennett works is that it’s invisible,” he says. “His hand is so sure and yet at the same time it’s invisible.

“You’re observing these characters in such an immediate way that you don’t feel the presence of everybody else and yet you know there’s a very strong hand guiding it. To be able to pull that off is unbelievable.”

![[L-R]: Amanda Villavieja, Laia Casanovas, Yasmina Praderas](https://d1nslcd7m2225b.cloudfront.net/Pictures/274x183/6/4/1/1471641_pxl_20251224_103354743_618426_crop.jpg)

No comments yet