Dir: Olivier Assayas. France 2010. 319mins.

The life, times and decline of a notorious figure are depicted in forensic detail and massively ambitious scope in Carlos, a hugely compelling if unwieldy three-part fictional biography of Ilich Ramírez Sánchez, the terrorist and revolutionary. Better known under his nom de guerre Carlos and - though the name is never used here - the media sobriquet ‘the Jackal’, Sánchez was a legendary headline-grabber in the 1970s, notably for taking hostage the delegates of an OPEC conference in Vienna and for a number of killings, for which he is currently serving time in France.

Compellingly serious, Carlos presents us with a very different era, politically and culturally.

Based on extensive research, the film nevertheless advertises itself in its opening titles as a fiction - partly because grey areas remain in Carlos’s biography - but comes across as a serious attempt to explore the career, motivations and personality of a figure who not only stands as an icon of a certain period of terrorism, but also represents many of the contradictions and complexities of modern international politics.

In Cannes, Carlos was shown out of competition in Cannes in its entirety, making for an only sometimes gruelling experience - notably in the final stretch, which flags slightly as Carlos’s career goes into decline and finally exhausted stasis. But the film was never intended to be seen in one marathon sitting. It is a three-part drama made for television - it was screened simultaneously with its bow on Canal+ - but is intensely cinematic and narratively driven.

It has definite potential for theatrical exposure, following extended two-part dramas on similar iconic figures (Steven Soderbergh’s Che, Jean-François Richet’s Mesrine), but might profitably be rejigged for cinemas - trimming and rearranging as a two-parter could be done without overdue compromise. In its full version, Carlos should find international television sales and ancillary success, plus festival exposure as one of the year’s major screen events.

The film shows Assayas switching with brio from his more familiar intimate mode (such as Clean, Summer Hours), without overtly playing the genre games of Demonlover or Irma Vep. Carlos comes across as a detached imaginative reconstruction, somewhat in the vein of The Battle of Algiers and Paul Greengrass’s United 93.

A hugely complex internationally-shot undertaking, the film not only skips locations with happy-go-lucky verve - Paris, London, Budapest, Beirut, Khartoum et al - but features dialogue in several languages including French, Spanish, English, Arabic and Hungarian, all apparently delivered with equal fluency by lead actor Edgar Ramírez.

Despite the three-part structure, the film is more of an organic whole than Che. The first section covers the rise of Venezuelan-born Sánchez in the 1970s, his enlistment with the PFLP (Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine) and a series of exploits including his involvement in the Japanese Red Army’s assault on the French Embassy in the Hague. Part two, dramatically the tightest, shows Carlos leading a hijack of OPEC delegates and his subsequent flight with hostages on a DC9. Final third shows Carlos in decline, as he becomes less an active militant, more a mercenary entrepreneur and a hunted celebrity, constantly on the move.

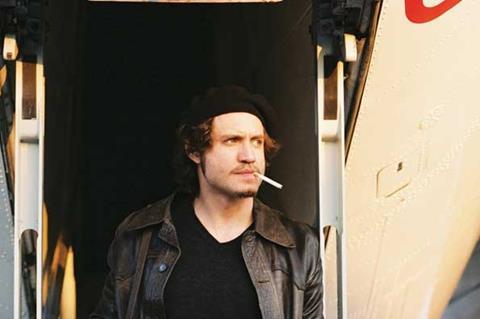

Compellingly serious, Carlos presents us with a very different era, politically and culturally, but never adopts the somewhat ironic, stylised attitude to the recent past that marked Mesrine and the 2008 German film The Baader-Meinhof Complex. Assayas and co-writer Dan Franck, using research by Stephen Smith, treat Sanchez’s career with journalistic seriousness, rather than adopting genre trappings - although the action scenes, executed with brisk urgency, exude thriller panache. There are incidental low-key comic touches, as the film deals with a now unimaginable period of casual security - a time when it was possible to waltz into OPEC headquarters unsuspected, while dressed in full Che Guevara regalia, beret and all.

A virtuoso editing feat of editing, the film skips propulsively between locations, using on-screen captions to introduce its multifarious dramatis personae - better-known figures including then-KGB chief Yuri Andropov, Sheikh Yamani and notorious lawyer Jacques Vergès.

Alongside Carlos, key figures include his sidekick Johannes Weinrich (Scheer) and the latter’s girlfriend Magdalena Kopp (von Waldstatten), who becomes Carlos’s mistress. Christoph Bach also impresses as ideologically and morally conflicted cell member Hans-Joachim Klein, aka ‘Angie’, with Ahmad Kaabour as Carlos’s PFLP boss Wadie Haddad, a constant in a labyrthine narrative of shifting allegiances.

The film never romanticises Carlos, although it depicts his own increasing tendency to romanticise himself: Sanchez appears as a complex, authoritative figure, horrifying but ultimately unknowable. His polyglot skills and protean appearance - from 1970s hipster to Che clone to paunchy mustachioed businessman - emphasise his elusive nature. Strictly covering two decades, early 70s to early 90s, the film doesn’t pretend to offer a back-story, although in a brief interview scene, Sanchez claims that he inherited Marxism in his blood. The film explores the applications of his adaptable, pragmatic Marxism, which variously takes in allegiances with the KGB and Saddam Hussein, while would-be freedom fighter Weinrich is happily in bed with East Germany’s Stasi.

At the film’s centre is an extraordinary performance by Ramirez, who plays Carlos as a charismatic, authoritative and deeply dangerous figure, plus a hardcore womanising macho. It’s a reserved, tightly controlled performance, Carlos only starting to lose his cool when his OPEC exploit starts going wrong. In part 3, living in permanent nomadic exile, his frenetic shoutings-down to his circle wax positively Hitlerian.

There are only a few awkward moments: notably, the initial bedroom encounter between Carlos and Kopp, when the film momentarily slips into the generic spy-sex mode that Assayas explored in his meta-genre exercise Boarding Gate. The film slightly runs out of steam in Part 3, where the drama is slowed down by excessive exposition and little decisive action - although it is part of the narrative logic to show Carlos’s life getting mired in stasis. The final build-up to his apprehension in Sudan by French security forces is a nail-biter.

Carlos ultimately comes across less as a character study than as a history lesson in the best sense, and proves one of the most achieved docu-fiction undertakings in recent cinema. Archive TV material is used sparingly, to good effect, as is punchy guitar-based rock, notably by Wire.

Production companies: Film en Stock, Egoli Tossell Film

French distribution: Studio Canal

International sales

: Studio Canal, (3) 1 71 35 35 35

Screenplay: Olivier Assayas, Dan Franck

Producer: Daniel Leconte

Cinematography: Yorick le Saux, Denis Lenoir

Editors: Luc Barnier, Marion Monnier

Production designer: François-Renaud Labarthe

Main cast: Edgar Ramirez, Alexander Scheer, Nora von Waldstätten, Ahmad Kaabour, Christoph Bach

![The Brightest SunScreen[Courtesy HKIFF]](https://d1nslcd7m2225b.cloudfront.net/Pictures/274x183/3/5/0/1448350_thebrightestsunscreencourtesyhkiff_312678.jpg)