Pride And Premieres: It has a complicated plot, but it’s a story worth reading nonetheless.

The set-up: Unbelievable. It’s 2020. Covid-19 has closed cinemas globally and put a screeching halt to production. The last big global festival to escape intact was the Berlinale. The last big blockbuster, Pixar’s Onward, sallied out bravely shortly afterwards but was felled by falling audiences and limped off online to Disney+. Millions of people stuck inside their houses are streaming like there’s a global pandemic on. Two significant European documentary festivals, CPH:DOX and Visions du Reel, have made the decision to go online in geo-locked and limited-ticketing formats. SXSW and Tribeca have cancelled, then gone partially online, but filmmakers aren’t sure which way to turn.

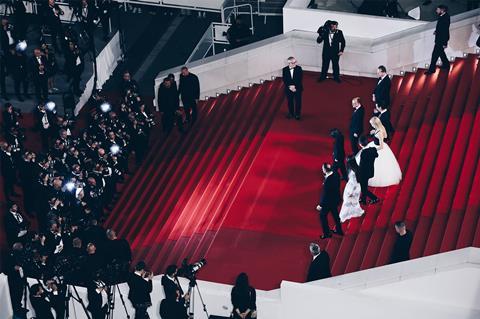

Last week, the Cannes sidebars cancelled.

The setting: Online is a galaxy for content; independent cinema needs a shop window before it can take its chances in there. But the sector is on hold. Cannes might yet declare a 2020 official selection, about 55 films at a guess, even if it can’t show the films. At the other end of the summer, Venice is banking on a sufficient relaxation of the Italian lockdown to mount some sort of public screening programme. The studios have held off dating any awards corridor after Toronto in September. Smaller festivals wedged in between would, by now, be securing titles (Jerusalem has postponed; Karlovy Vary and Locarno have yet to declare). But how can you plan, whether it be for a national-only event, or public or online screenings or a mix of both, when social distancing guidance seems to change every day and premiere status continues to be a sticking point?

(Your commercial confidence and positive attitude to all this also depends – to a great extent – on where you live and where your country is on the curve, as may be made evident in the online-only Cannes marche in June.)

Major players include: Thierry Frémaux, Cannes delegate general. He heads the most important film festival in the world. Producers, directors, sales agents all want to be in it, and he won’t give up, although it’s safe to say his obstinacy is now frustrating the industry. Alberto Barbera, the head of Venice, and Roberto Cicutto, president of the Biennale (who, to complicate matters, either aren’t singing from the same hymnsheet or playing good cop/bad cop). They want to forge ahead and their prospects are buoyed by the fact that Venice is a small festival which takes place on an island. In Toronto, Cameron Bailey, head of the most powerful North American festival, has to deal with how public-facing and dependent on ticket sales his festival is. Fremaux and Barbera share a burning urge to preserve cinema in its purest form as a big-screen theatrical experience; Bailey and his team are more flexible. All need to safeguard the prestige and status of their festivals. Potential flaws include pride and premiere status.

The burning questions: Is premiere status demanded by A-list festivals still valid, and if not world, then national or international, or online – how much do they matter in the time of Covid? Agents are crystal clear that their talent won’t be pressing hands in the flesh at red carpets this year. Would a geo-locked online premiere at a smaller festival jeopardise a filmmaker’s chances for showing their “international premiere” at another, perhaps larger, more covetable event (for which the selection hasn’t yet been announced)? Some sales agents are talking about a complete holdback to Sundance or Berlin, or even Cannes of 2021, given the production pipeline is also broken. (There may be light at the end of the tunnel for it to resume – albeit in a much more expensive format favouring the larger players, at least initially.)

The conclusion: The industry is in a bind. The next move by Cannes will loosen some of the cords, but not all. There are vested interests in preserving the status quo, from individual egos all the way up to national pride, but as borders shut, should film follow suit? Not all titles are against creating new opportunities in how they are launched. If one festival or director believes only in the big-screen experience, should this deter others? Filmmakers should ideally be free – and feel confident enough – to find partners on the festival circuit who will work with them in whatever way they want – it’s their film, after all. Whatever the attitude – “purist”, or willing to experiment with formats – the time is right for the entire festival circuit to pull together visibly and publicly to restore confidence in the sector.

A final note: Ultimately, and it’s worth bearing in mind as pronouncements and announcements from festival chiefs trickle in, epidemiologists and politicians are calling the shots now.

They’ll be the ones to tell us when next we meet in a darkened cinema again.

No comments yet