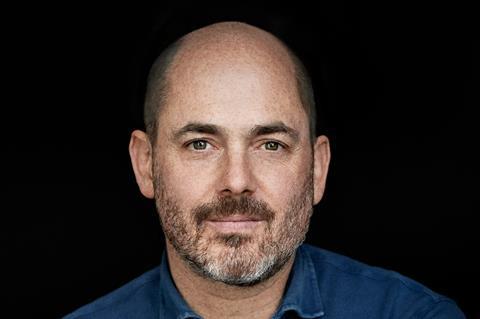

All Quiet On The Western Front is a German literary classic, but the First World War novel has never been filmed in its native language — until now. Director Edward Berger tells Screen why the time was right to bring the story home

It is one of Germany’s most revered novels, whose title alone has become synonymous with anti-war sentiment. The 1930 film adaptation was a landmark in Hollywood history, scooping two Oscars including best picture. A TV version followed decades later. And yet, for more than 90 years, despite its enduring resonance for Germans of all generations, All Quiet On The Western Front had never been made as a German film.

Until now. Edward Berger’s adaptation for Netflix finally brings Erich Maria Remarque’s traumatic account of the trench warfare of the First World War “home”. In the process, he has made an emotionally powerful, anti-war epic. Appropriately, it is Germany’s official submission as best international feature for the Oscars.

But why did it take so long? “It’s a very difficult question,” Berger muses. “Maybe opportunity, because films like this are not cheap and they’re difficult to get financed — usually you need the English language, with a star who warrants that type of budget; and we were, somehow, able to make the film quite cheaply. Also the opportunity of language — I think people are now more open to having authentic language, whether it’s from Indonesia or Germany or Spain. The time was right for that.”

He adds another, more profound reason: historical distance. “There’s a big sense of guilt or shame about both world wars,” he says. “Germany had one of the decisive, if not the decisive part to play in causing the First World War, as well as the Second. Put them together and that’s one big, dark spot on your soul. It’s hard to address and hard to talk about.

“But, also, that was the driving factor for me to make the film — to talk about it. Germany fighting those two wars is a big part of my life, a big part of my DNA. I was born in 1970, but I remember so well, from my childhood, feeling ashamed of being German.”

The generational impact was also reflected in his teenage daughter. After producer Malte Grunert proposed the adaptation to Berger, he mentioned it to his family over dinner. “At those times, our kids always get up and say, ‘Next movie, who cares?’ But I mentioned the title and my daughter, who was 17 at the time, whips around and says, ‘That! You have to make it. I just read it in school. It’s the best book I’ve ever read and made me cry seven times.’ So it still had a relevance to her, 100 years after the First World War.”

German perspective

The genesis of the project was a script by UK writers Lesley Paterson and Ian Stokell that came to the attention of Grunert. Once Berger signed on, he started work on another draft himself. “Theirs was a wonderful version, but I did feel that for it to be made again, it really needed a German perspective.”

He admits that perspective is not so easy to define. “But I would say, no hero’s journey, nothing of pride or honour in what the character does. In this film, we tried to say that every death is a terrible death, no matter on which side. I had a hard time using the word ‘enemy’, because I’m using it about French people, who in my mind are the good guys in the war.”

The novel follows young German Paul Bäumer and his friends, who enlist enthusiastically in the early years of the war only to lose their innocence and their lives in the trenches.

Berger has added a new, historically accurate plot element — involving the negotiations that bring the war to an end — led by German diplomat Matthias Erzberger (Daniel Brühl, who also serves as an executive producer on the film) and which in many ways are the seed for the Second World War. “The book was written in the 1920s. Now we have the perspective, 90 years later, that this was just the beginning. There was a bigger terror to come. I wanted to shed a light on that.”

Hitherto best-known for directing a pair of acclaimed mini-series — International Emmy winner Deutschland 83 and Bafta winner Patrick Melrose — Berger admits that nothing in his previous work prepared him for making a war film. “It was new territory, and that’s always very important for me, that I have to tackle a new challenge. I guess it keeps me on my toes.”

He and cinematographer James Friend, who had worked together on Patrick Melrose and Berger’s three episodes for HBO’s Bryan Cranston series Your Honor, were afforded an opportunity by the pandemic to lay the groundwork. “We spent about three months locked together in a hotel room in Berlin,” says Berger. “I went home at night, but he flew over for two weeks at a time, went home for a few days, then came back. And so we storyboarded every day, especially the battle scenes. I have this bible that’s probably 300 pages thick, just drawings. If you put the storyboard next to the movie, it’s pretty much the same. It made an enormous difference during the shoot, it just helps you stay sane.”

There was still pressure, of course, not least the physical ordeal of filming action sequences on their enormous set — a former airfield in the Czech Republic that they had dug up and turned into several hundred metres of trenches and a no-man’s land the size of two football pitches. And then there was the mud.

“It was an extreme shoot,” Berger laughs. “Sometimes people sank into the mud and you had to get a crane to get them out. The prop guy came to me after shooting one evening; he had one of these fitness bands, and said he’d run a half marathon that day, just carrying stuff around.”

Berger cites Laszlo Nemes’ 2016 Oscar winner Son Of Saul, about a prisoner in a concentration camp, as “a subconscious influence” for the film’s focused perspective and sense of immersion. “We’re not as radical, because our film has a broader scope; he’s really concentrating on that one character. But I did want the audience to feel grabbed by the lapels and dragged through the mud with Paul, to feel what he feels. So that after the film you feel the weight of it — you take it home for an hour, or overnight if I’m really lucky.”

For Paul, one of the most iconic characters in German literature, Berger cast an Austrian theatre actor, Felix Kammerer. “We found him in the Burgtheater in Vienna,” he says. “He had never been in front of a camera, but he was fantastic. He was so eager to learn and by day one of the shoot he was in an immediate dance with the camera. He was the right age to convey innocence, as well as a certain wisdom or jadedness, so he could play both ends of the film.”

Netflix was on board from the outset and holds worldwide rights. The film began streaming on the platform in late October, but has had theatrical outings in numerous countries, including Germany, the US and the UK. It is in cinemas that Berger — whose next assignment is an adaptation of Thomas Harris’s papal thriller Conclave, starring Ralph Fiennes and filming in Rome from January — has been feeling the continued relevance of the anti-war message.

“I went to New York, for example, and this woman came up to me after a screening and said her dad was in Iwo Jima,” he says. “He died three weeks before the end of the war, with a picture of her — 15 months old, she’s 80 now — and her mother in his pocket. You realise everyone all over the world has some kind of story or scar because of these wars.”

Filming ‘All Quiet On The Western Front’

Director of photography James Friend aimed not just to put the audience on the battlefield but running across it, as if they too are under fire

All Quiet On The Western Front is the third collaboration between Berger and UK cinematographer James Friend, after TV series Patrick Melrose and Your Honor. Friend speaks fondly of his director as “like an annoying older brother” and says they have “forged a fantastic working relationship and friendship”. Like Berger, Friend cites their months-long storyboarding as key to their achievement on the film.

“We had this unheard-of luxury, especially coming from television, of just visualising the film, shot by shot and scene by scene, in a very comfortable environment, with good old-fashioned pen and paper,” he says. “It was a wonderful creative process, because normally as a DoP you get brought in with very limited prep time, sometimes the sets have already been erected, the crews already established. And I really felt that I’d been brought in at an embryonic stage that enabled me to be a better filmmaker, cinematographer and storyteller.”

Friend speaks of “a relatively modest budget for what we were trying to achieve”, which included major battle scenes. He chose to shoot a lot of the drama on the Arri Alexa 65. “I love the way it renders portraiture and spaces. It adds a dimension — the field of view is so wide, it almost feels like you can reach into the screen.” But for the action scenes, “we dropped down a sensor to the Alexa Mini LF, which proved the perfect tool to navigate through trenches, and large-format enough for it to move seamlessly into the work with the Alexa 65.”

His and Berger’s aim was “to put the audience on the battlefield, and running across it, feeling like they are being shot at. You can actually hear the breath of the soldier next to you and you can feel the bullet whizzing past.

“With that came a huge logistical challenge — how do we poetically move a camera through a space that is basically a battlefield, with the [uneven] terrain and mud like you can’t imagine. It was the most difficult, gruelling experience, technically, that I’ve ever had, and emotionally as well, because it takes a lot out of you to shoot just horror and death and destruction and human savagery.”

Friend recalls phoning his father from his hotel and sharing the pressure of the day’s shoot. “He said to me, ‘Your great-grandfather fought in this war and was in those trenches, and survived, and his brothers didn’t. You get to do however many hours in that space, and you come home physically and mentally exhausted, but at least you go back to a hot shower, a hot meal, and a comfortable bed. And also do what you love.’

“That resonated with me. It was an extremely sobering conversation, which made me realise that actually it’s our duty as filmmakers to retell this story for a modern audience. I didn’t really complain again after that.”

Friend is currently shooting The Acolyte, the latest Star Wars television series for Disney+. “I’m a Star Wars nut, so it’s a dream come true.” He is also planning more collaborations with Berger. “We’re already talking about the next one, and the next… Otherwise, I’ll become a landscape gardener. Or a monk.”

![The Brightest SunScreen[Courtesy HKIFF]](https://d1nslcd7m2225b.cloudfront.net/Pictures/274x183/3/5/0/1448350_thebrightestsunscreencourtesyhkiff_312678.jpg)

No comments yet