The successive leaders of Channel 4’s filmmaking division discuss the ups and downs, highs and lows, of four decades of existence as a shining beacon of the UK film industry.

In November 1982, Channel 4 — the UK’s fourth TV channel — burst onto the scene, with a mission to offer a distinct and innovative alternative to the television diet. Entrusted by founding Channel 4 CEO Jeremy Isaacs with steering the drama output was David Rose, a veteran executive who had made his name in theatre and at the BBC.

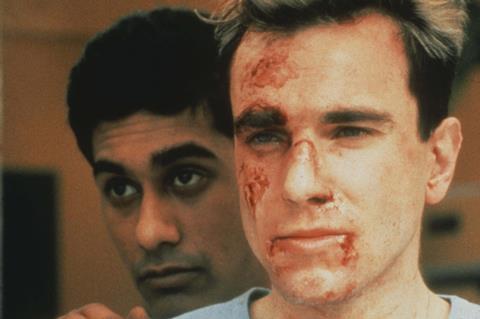

A key element of Rose’s output was single films, aired under the Film On Four strand — and Rose found increasingly that he was putting his energies into features, with support from his team Walter Donohue and Karin Bamborough. The channel’s emphasis on film deepened when select titles were released first into cinemas, notably including 1985’s My Beautiful Laundrette, directed by Stephen Frears from an original screenplay by Hanif Kureishi.

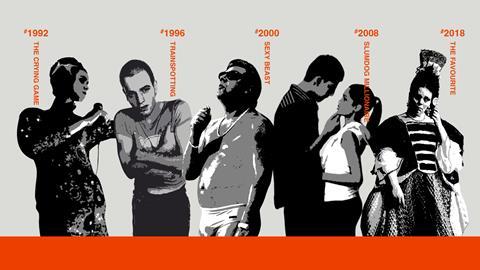

Under the successive stewardships of Rose, David Aukin, Paul Webster, Tessa Ross, David Kosse, Daniel Battsek and Ollie Madden, Film4 (as it became known) established itself as a major player in the UK film industry, developing, producing and investing in films that have helped transform the identity of the British film brand: from The Crying Game to Trainspotting, Sexy Beast and This Is England to best picture Oscar winners Slumdog Millionaire and 12 Years A Slave.

Evolving scale

On November 23, at this year’s Big Screen Awards, Screen International will present Film4 with the outstanding contribution to UK film special recognition award, spotlighting the company’s enduring impact. To mark the occasion, we tell the story of Film4’s evolution over four decades, told in the words of the senior leaders who steered the ship.

The scope and scale of Film4 has evolved over that time, and its directors have navigated changes in aspiration at the top of the channel, as well as changing economic circumstances and the ebb and flow of advertising revenue. The mission, however, has remained constant, as current Film4 chair and former director Daniel Battsek discovered when researching documents for the 40th anniversary of Film4 last year.

“The policy of Film4 is to provide opportunities for filmmakers to produce films of individuality and distinction,” Rose wrote to Isaacs in 1985. “Films that might otherwise not get made, or which might be deemed too controversial or adventurous. A substantial number should be the feature film debut of writers and/or directors.”

“It could be written today for Film4,” comments Battsek, who adds it was the film output of Channel 4 that inspired him when he was starting out in the UK film industry in the 1980s. “Those are the sorts of movies that I wanted to make, those are the sorts of filmmakers that I wanted to be participating in their journey to the screen,” he recalls. “I remember seeing My Beautiful Laundrette at Edinburgh Film Festival in 1985, and thinking, ‘That’s what British independent filmmaking should be.’”

Channel 4’s filmmaking arm was initially called Channel Four Films, and then incorporated into a separate company, Film Four, which was renamed Film4 in 2002. We are referring to the company/division as Film4 throughout.

Karin Bamborough

Assistant editor, then commissioning editor for Film On Four, 1981-91

While working together, David Rose and Karin Bamborough became romantically involved, and they married in 2001. Rose died in 2017.

We were informed by the ethos of the channel as a whole, which was to be innovative in form and content, to give voice to those who had not had a voice. We were keen to encourage independent filmmakers, and there wasn’t much opportunity at that time for them. We didn’t have an agenda beyond enabling as many interesting films and filmmakers to get made as we could.

David [Rose] was clear that he wasn’t making films for television, he wasn’t making films for the cinema, he was making films. And if they had cinematic potential, then they would be free to have a theatrical release… which caused some scheduling problems.

By the start of the 1980s, we had hit a fallow period [for British films]. So the timing of Channel 4 was very good — it helped kickstart the whole new energy. There were directors like Stephen Frears, who had done fantastic work, and got a chance to go back into cinema. We helped kickstart the whole cinematic flowering for Mike Leigh again. It had been a while since he’d done a feature for the cinema [Bleak Moments, 1971].

My Beautiful Laundrette began by me asking Hanif [Kureishi] if he’d like to write a film for us. I’d seen his work in theatre and thought he was an interesting voice. He came back three months later with My Beautiful Laundrette – which bore no resemblance to the story he told me, but was really interesting, so we were happy. None of us expected it to be as commercially successful as it was. Our sales department thought there was no hope for it whatsoever. David had much more confidence once it was made. He pushed it to go into Edinburgh Film Festival.

This proves that nobody knows anything. It was a film that was made with energy and conviction, that had something to say and spoke to the audience.

Then with [Kureishi’s] Sammy And Rosie Get Laid, I have one particular recollection. There was a scene in which there were riots in the street, buildings get burnt, cars are exploded. Hanif is standing there as the flames go through the building, and 50 riot police are beating 50 protesters. He turned around and said, “All I wrote was one little line: ‘There is rioting in the street.’” The power of the word!

David Aukin

Head of drama/head of film at Channel 4, 1991-98

David Rose retired in 1990, and after a brief interregnum was replaced by David Aukin. Aukin recruited Jack Lechner and Allon Reich as his key creative executives, promoting Reich after Lechner departed.

I had come from the world of theatre. I was running the National Theatre with Richard Eyre, so it was a very controversial appointment.

There were lots of issues and pressures. I knew the sword of Damocles was hanging over us for a number of reasons. The economy was going through a terrible recession. There were cuts in budgets. And our funding formula — whereby we were funded by ITV as a percentage of their advertising, which they collected both for Channel 4 and ITV — was going to be abandoned at some point. We would have to earn our own advertising revenue, and have our own team to do that, all of which was very risky.

One of the first things I did was to search for a good script editor to be head of development, and David Puttnam suggested an American called Jack Lechner who worked with him at Columbia [Pictures]. I organised for him to come over and meet, and you could tell he was very good. I knew when it was announced, [critics would say]: “First of all they appointed a man from the theatre to run Film4, and then they employ some arsehole from Hollywood to tell us how to write scripts.” But Jack was brilliant, and writers adored him. He was only with us for three years, but his input was very important.

I went to [programme director] Liz Forgan, and I said, “There isn’t a handbook that tells me how I’m supposed to do this. What are the rules?” She said, “There is only one: you’ve got to have passion for everything you do, that’s the only rule you mustn’t break.” That was an amazing freedom.

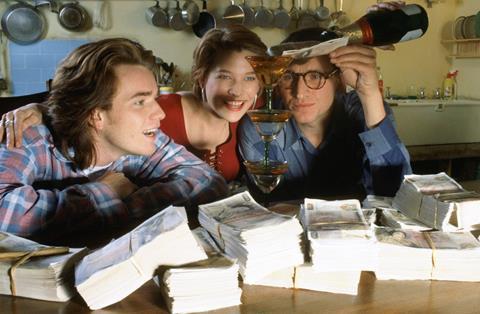

The most important film in terms of the development of my slate was unquestionably Shallow Grave. This came from an unknown writer, an unknown producer — and normally these [unsolicited] script submissions are rubbish. When I started reading, I couldn’t stop — it was a wonderful piece of writing by John Hodge. Jack and Allon [Reich] were equally enthusiastic about it. Andrew Macdonald and John came down to meet, and we gave them a list of potential directors. They came back and said they wanted Danny [Boyle], and that’s how the team came together.

Why it was so important was that everyone was talking about the demise of the British film industry, and that people seemed to avoid going to [see] British films. Not only was Shallow Grave the perfect film for Film4, but it struck a nerve with a younger generation.

The other important element of it was Michael Grade — I showed it to him and he loathed it. He said, “I don’t think I can even transmit this film.” Fast forward six months and the film is sold all over the world, and it wins the first prize at Dinard Film Festival. The prize is given to Danny Boyle by Michael Grade and he bought two huge magnums of champagne, and it was fantastic. He was now fully behind Film4, and the sword of Damocles was lifted.

There was that famous moment when Colin Welland, the writer of Chariots Of Fire, held up his Oscar [in 1982] and said, “The British are coming!” There was this sense that we could take on the Americans, and I made it one of my rules: the function of Film4 was not to take on the Americans, it was to provide an alternative. There was an alternative audience out there that was interested in something in addition to American films. We don’t always know what that difference is, until we see it. In other words, we’re not making a mass-produced product, we’re making prototypes every time.

With Four Weddings And A Funeral, PolyGram was financing it but wanted a partner. Tim and Eric [Bevan and Fellner, executive producers] needed someone to put up £800,000. They went all around town and as a last resort, they came to Film4, which they didn’t necessarily think was an obvious fit for the film.

When I went on set, Mike Newell [the director] was in a state. He said, “David, you’ve got to find me some more money, I need another week to shoot.” I said, “Mike, I can’t.” The question I later asked myself was: if I had found that money, would we have had a better or more successful film? It’s cruel, because clearly the answer is no. There was something about the working conditions that did give an energy to the film that might not have been there with more resource.

Of course, with our success, the whole British film industry got a huge surge of confidence and more and more people wanted to get involved with films. So then there was more competition for interesting work.

Allon Reich

Script editor/deputy commissioning editor for film, Channel 4 1991-1998

When David [Aukin] first came, there was a real desire to try and make films that seemed like they fit in a cinema, and for a slightly younger audience. Three of the first things we commissioned were Shallow Grave, [Paul WS Anderson’s] Shopping and [Richard Stanley’s] Dust Devil. Obviously Shallow Grave was way more successful than the other two, but they all combined to give a notion of a more indie genre and contemporary feel. Andrew Macdonald was saying, “We want to make quality populist films,” and they were jealous of the Coen brothers.

David was giving a talk at a Scottish festival, and Andrew gave him an envelope with the Shallow Grave script. David never read scripts, at least not until Jack or I had read it first, but he was getting on a plane, he had forgotten his newspaper, so this was the only thing he had to read. He came into the office the next morning, chucked it down on my desk and said, “Read that, I think we should do it.”

After we made Shallow Grave, I remember Andrew saying, with some degree of regret, “We’ve made a movie that is relatively commercially successful, but now we want to do something that we know will never make any money: a film about drug addicts in Scotland.”

And then John [Hodge] took out the book of Trainspotting. They said, “This is what we want to do, we’re absolutely passionate about it, and we’ve got an idea of how to do it.” David flipped through it, and went, “Yeah, brilliant,” and sort of edged the book to me.

Andrew gave me the first draft of the script to read. It didn’t have an ending at that point, so it was just 90 pages. I was blown away by it. John had managed to somehow get it into 90 pages, so you felt nothing was missing, even though three quarters of the book wasn’t there. The key was to make Renton the protagonist, which is slightly less clear in the book. The screenplay made it very clear who the lead character was, and it felt all the things that the movie ended up being, which is brutal and hilarious and extremely poignant.

Four Weddings and Shallow Grave dramatise very different ends of the UK, both socially and geographically, but they heralded important new voices and filmmaking teams, working in recognisable movie genres that aimed to engage with an audience while also, in their different ways, reflect life in contemporary Britain.

The growth of these and other voices coincided with an economic upturn and the rise of PolyGram, Miramax and Fox Searchlight who began to see the commercial opportunity of UK films in the burgeoning US and international arthouse crossover business. Channel 4’s support was, and remains, crucial in cultivating and supporting the talent that continues to make the industry thrive.

Aukin departed to set up the short-lived Miramax division HAL, which he co-founded with Trea Hoving and Colin Leventhal, and Reich joined him there. Paul Webster, who at that time was head of production at Miramax, replaced him at Film4, now a standalone company with international sales and distribution.

Paul Webster

Head of Film4, 1998-2002

What was presented to me was: we have now become a major force, thanks to the two Davids. We’re doing very well — and we’re losing money hand over fist. So we want you to turn Film4 into a business.

The challenge was to keep up the ethos of being a friendly place for the British filmmaking community to come to make films, but also to create a business — which was an impossible circle to square. Especially because not only did Michael [Jackson, Channel 4 CEO, 1997-2001] and Channel 4 want successful movies, they also wanted high art movies.

Webster recruited James Wilson from Fox Searchlight and Elinor Day from the BBC to be his lead creative executives. Notable films from this era include Jonathan Glazer’s Sexy Beast, Damien O’Donnell’s East Is East, Asif Kapadia’s The Warrior and Paul McGuigan’s Gangster No. 1.

Gangster No. 1 was a good experience. It was Norma Heyman producing and absolute world war three with the writers. Jonathan Glazer was originally on that movie as director, and [writer duo] David Scinto and Louis Mellis were very powerful characters. They got [Glazer] on Sexy Beast instead, and I put Paul McGuigan on [Gangster]. Hardly anybody went to see that film but I thought it was rather good.

Around 2000, I was sent the first 100 pages of a novel called The Lovely Bones. I read it, and it was fantastic. I optioned the rights for $10,000 and then the book got finished and became one of the biggest-selling books of that time.

I immediately exercised the option so that we owned it for $100,000, which drove everybody in Hollywood mad. We had CAA on us, Jeffrey Katzenberg, everybody wanted to do this and we said, “No, we’re going to do it.” We had Lynne Ramsay, who was having a terrible time adapting it, and of course, Peter Jackson ended up directing it.

I loved making Buffalo Soldiers [about US soldiers dealing drugs on an army base in Germany] with Gregor Jordan, starring Joaquin Phoenix. We took it to Toronto in 2001, sold it to Harvey Weinstein for a chunk of money, and had an amazing screening there. We signed the deal on September 10, and by September 11 that film was unreleasable.

Harvey test-previewed the film in New York, and it did not score well. There was a focus group afterwards, and people said, “This film casts America in a negative light and must never be shown.” And a woman in the focus group said, “No, I grew up on an army base in Germany and everything in that film was true”, which it was, it was all factual. But she agreed it should never be released. That was the end of Buffalo Soldiers.

In 2002, Channel 4 ended Film4 as a standalone company, shutting down distribution and international sales. Webster exited, and almost the whole team was laid off.

We were not making a lot of money, that’s for sure. And I made some mistakes. Michael [Jackson] had left and that was my protector gone. Mark Thompson [Channel 4 chief executive, 2002-2004] came over for a year or so in terminator mode and decided to shut down Film4.

In declaring independence from the channel, we didn’t pay enough attention to the relationship with the director of programmes and the film acquisitions unit, because they were buying films to broadcast. So they could buy them for £50,000, and here we were making small movies, which cost £1m per film. The currency of film on TV was diminishing, and we were making films that were put on at 2am. So there was a disconnect there.

When Tessa [Ross] took over, she was magnificent. She never took credit for anything that wasn’t hers. Let me stay on The Motorcycle Diaries [as executive producer] throughout. I have not one cross word to say about Tessa, she was a joy throughout. And very astute.

Tessa Ross

Head of film/controller of film and drama at Channel 4, 2002-14

Tessa Ross was working at Channel 4 as head of drama. She moved over to become head of film, with an annual budget of £10m (later £15m) for a scaled-down and more focused Film4. Creative executives recruited by Ross during her tenure include Juliette Howell (now her partner at House Productions), Katherine Butler, Sam Lavender, Rose Garnett (now at A24) and Anna Higgs (now managing director of talent agency Casarotto Ramsay & Associates). Eva Yates began as an assistant and is now director of BBC Film.

When I was at British Screen, I had a relationship with David Rose and his successor David Aukin. I always thought David Rose was the best person in the world. He was completely the person I wanted to be when I grew up. At British Screen, Peter Chelsom’s Hear My Song was happening. The thing I remember most is the gentle grace with which David gave notes, and me thinking, “That’s how it must be done.”

My perspective was that all the pressures on Paul were the wrong pressures for a broadcaster: they were bottom-line pressures. And having taken on such a huge overhead and effectively doubling up every investment with finance and distribution, every choice had to be doubly successful.

Mark Thompson threw away the development slate and said, “We’re going to start again.” I had to rewrite a vision, a mission, for how a broadcaster viewed its relationship to the film industry and to film.

We had to build the films that represented the brand, which was bold, new, forward-thinking. Build projects that you were 100% behind from the moment you started them, and spread your money as widely as possible, to make sense of being able to be necessary in every film. My argument was: the worst that can happen is that films that stand for what Channel 4 stands for are on your television channel, and you own the rights to play them. And the best that can happen is we build great movies.

Our attitude was that being absolutely clear what you are, and being sustainable, was important [to the film community]. People know what you’re there for, and know what you do. And it meant that people felt it was home.

I always felt it was all balanced on a pinhead: a combination of quality and money, minimising risks, getting the best for everybody, making sure that if there was money to be earned, we earned it, but not so much that money became a priority. How do you balance those things?

Shane Meadows came and he pitched a comedy. He said, “I’m going to make a film about a superhero on an estate.” I thought, this is amazing. This is my first commission at Film4, I’m going to work with Shane Meadows. And in came an outline for Dead Man’s Shoes, the most serious revenge drama I’d ever read. But it was absolutely brilliant.

The relationship Shane developed with producer Mark Herbert was brilliant, and we had a good relationship too. That feeling safe, so that when you’re challenged, it’s a good challenge, is so important. For creative people to think, this is a good place, I trust these people, and if they ask me a question, they’re not giving me notes because it’s their job, they’re asking questions because they care. It was about making the industry bigger and better and bolder and safer.

The success of Slumdog Millionaire was a red rag to the bull. The [culture] secretary at the time, Jeremy Hunt, said, “Why didn’t you make more money?” I said, “Well, we only put in this much equity, and we got it made.” Nobody wanted to develop it with us; Warner Bros pulled out when they saw it. It’s not like everybody knew what it was going to be.

Thank goodness, we made Martin McDonagh’s first movie [In Bruges] with the rest of the money, and Mike Leigh’s [Happy-Go-Lucky] and [Steve McQueen’s] Hunger. We made 400% on our investment in Slumdog. It’s just we didn’t invest £10m, we invested a proportion of the budget. And they just didn’t understand.

Anna Higgs

Commissioning executive at Film4.0, 2011-2013, head of digital/creative executive at Film4, 2013-2015

Film4 had a history of supporting low-budget filmmaking, sometimes via a separate strand, such as Film Four Lab, which was run by Robin Gutch in the Paul Webster era. Ross launched new digital initiative Film4.0 in 2011, inviting independent producer Anna Higgs to lead on it.

Film4.0 was quite a loose brief when I joined. My job was to grasp the nettle of how the landscape was changing: audience patterns are changing, models are changing, what do we do with this digital world?

So I set up a strategic framework of: would Film4 make this regardless of how innovative [the digital component] was, and is it a filmmaker we want to develop a relationship with? There was a bunch of other stuff, but it had to pass those two bars first.

People saw, oh well, Film4 rejected this before, but maybe this new weird thing can do it. No, that’s not how it works. It helped me manage expectations and be quite clear both within the team and externally. I came into the team having been a practitioner producer rather than having come up that traditional development and commissioner route, so I wanted to be quite practical and hit the ground running. We had a £1m annual budget.

We fully financed Ben Wheatley’s A Field In England, and we’d never done that before, at least not under Tessa’s regime. Are you opening the floodgates doing that… but the combination of the filmmaker, the idea, and the proposition meant that we could take that risk. Ben had been going up the ladder of [production scale], and he came back down to make a film in two weeks. From our first chat to it being out in cinemas was less than a year. It was an extraordinary pace, as well as an extraordinary model.

One of my favourite experiences was 20,000 Days On Earth. That’s a good example of Film4 breaking rules and evolving a form and a genre. Iain [Forsyth] and Jane [Pollard] are extraordinary filmmakers. Their pitch document is so close to the film we got in the end, and everything that happened after that was only elevatory. You might think, who’s going to see a Nick Cave film outside of Nick Cave fans? It’s that line from the movie when Nick says, “It’s about the moments when the gears of your heart change,” and how we’re all creative.

It was critically successful, won a prize at Sundance, was nominated for a Bafta. It was the highest-grossing box office documentary that year, we did this amazing simultaneous release, with the heart event in the Barbican. The marriage of great talent, interesting idea, beautiful filmmaking and getting a whole team behind it. We worked with Picturehouse [Entertainment], and we thought about all of those strands, right the way through – we didn’t think about distribution when the film was finished.

We ended up quietly dropping the Film4.0 brand. [The name] meant that some people could relegate it to: that’s the world of DVD extras and other weird stuff you do at the fringes. And actually, for the innovative work to have its full chance, it had to be on exactly the same quality authorship excellence benchmarks of everything else that Film4 does and did.

Rose Garnett

Head of development/head of creative at Film4, 2013-2017

In 2013, Ross invited Rose Garnett, then working as a freelance script editor, to join the team, and she became a key creative member, exiting in 2017 to become director of BBC Film.

What was my perspective on Film4 [before joining]? That it was where the action and energy was. I’d known Tessa on and off for years, and admired her very much – for her vision, creativity, and having built this identity for what film could be out of the UK. She was a very talismanic figure.

I find it hard to talk about any one film. What was so extraordinary about Film4 was its place in the landscape, and the embrace of authorship, and story, and how it was greater than the sum of any one film. It was about building a story within what we could do in Britain, in terms of cinema that could amplify in a global way, but also being able to make a filmmaker’s first film so they find their voice and place in the world. Having that remit was very rare, and a real privilege.

In my four years there, I think we made some great films, and that’s ultimately what matters – and I hope in an environment that was thoughtful and supportive. Even though some things changed around the way we worked, our job was always to support from a public service point of view, not from a market point of view.

Public service at its best is not around niche or obscurity, it’s about being able to identify what people will want to watch, in a non-reductive way. It’s easy to think public service sits in opposition or it’s anti-market. It’s absolutely not that. It’s about having the confidence and bravery – because that’s your job, not because you’re intrinsically confident or brave – to make the work that is going to help contribute to the bigger landscape of stories being told. And one of the ways you do that is by people seeing it and the work being successful. It’s not about niche or indulgence or navel-gazing, it’s about having the privilege to be able to look ahead, in a real way.

I loved them all [the films the team made]. I didn’t love them all, actually, but we made them all for good reasons. Being somewhere where you could be part of American Honey, The Favourite, I Am Not A Witch and You Were Never Really Here, that’s a pretty amazing place to work.

David Kosse

Director of Film4, 2014-16

In 2014, Ross left to run the National Theatre, later setting up House Productions. After a major search, Channel 4 appointed David Kosse as her replacement, a US-born senior industry figure with spells under his belt running Momentum Pictures and Universal Pictures International.

The Channel 4 board and executive felt that Tessa’s group had done a tremendous job with very little money of raising the profile of Film4 and supporting the British film industry, and they were coming off a best picture Oscar win with 12 Years A Slave. But they were going through a moment of fiscal questioning. They were asking me, “Don’t reduce the quality, and stay with the remit, but can you lose less money? We don’t want you to just go make a bunch of commercial films.”

There was also a little bit of pressure from the broadcasting side of the business going, “These films are wonderful, but that’s not what we want at 9pm on Channel 4. We have to run them on [digital channel] Film Four.”

The real change in the strategy was to put more money into fewer films and to improve the recoupment position, so that in the event of a success, one could achieve a good commercial return. We also had more control over the creative process, by being a 30%, 40%, 50% equity investor.

We were also putting pretty big investments as a proportion in one or two low-budget movies. So there were three categories: let’s make a couple of £2m movies with first-time filmmakers; let’s be a minority investor in some £4m or £5m movies that we think are creatively brilliant, but risky financially; and let’s take big bets on one or two bigger films. Martin McDonagh’s Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri was the latter strategy, as were The Favourite and Fighting With My Family.

As for the smaller investments, I tried to get a little tougher with sales agents, distributors, the BFI and banks [by improving Film4’s recoupment terms]. This is not a criticism of the previous policies, but what was happening was that non-UK companies were disproportionately benefiting from our early and risky investments — beneficiaries included French companies like Studiocanal and Pathé, US studios like Fox and Universal via Searchlight and Focus, and Canadian company eOne. We were giving filmmakers in the industry a leg-up, but I felt there was too much of the British government’s money going to non-British companies.

Tessa did all the development work on Lenny Abrahamson’s Room and she was gone before I got there. There was a moment where it had to be greenlit — it was a yes or no decision, and I was the one to say yes. Lenny showed the first cut, and I said, “This movie is going to be nominated for best picture. Believe me, there’s just no way there’s nine better movies than this.” I had loved working with A24 on Ex_Machina [at Universal] and I really pushed them on the Academy campaign. A lot of my background is marketing and distribution, and on Room I felt like where I could contribute was as a marketing and distribution and awards campaign guy.

I wasn’t there that long to make a mark, and I don’t think it’s a dramatically marked difference in terms of the creative direction, with the exception of a handful of projects. I think maybe I broadened the types of films a bit. Remember, it wasn’t just me. The entire team under Tessa stayed, and they continued to have a huge impact on the types of films we pursued. As for the ones I personally championed, they were movies like Three Billboards, Fighting With My Family, American Animals and Michael Pearce’s Beast. American Animals is one of my favourite films I’ve ever been involved with, from start to finish. Fighting With My Family is a great, crowdpleasing movie.

Film4 has a history of those kinds of movies. I watched those Film4 movies in the ’80s and ’90s that were both creatively great and had big audiences. I wanted Film4 to be edgy and commercial and cool, as well as highbrow. I was looking at thrillers like Shallow Grave and thinking, “When was the last time Film4 made a movie like this?”

Daniel Battsek

Film 4 director, 2016-22, chairman, 2022-present

In 2016, Kosse joined STX to run a new international division, and was succeeded by Daniel Battsek. Battsek had made his start in the UK film industry at Palace Pictures, going on to run Buena Vista International before relocating to the US for roles at Miramax, National Geographic and Cohen Media Group. He was promoted to chairman of Film4 in 2022, with Ollie Madden taking over as director.

Before Film4, the UK film industry looked to me like it was run by grey people in business suits and old school ties — and that’s everything I had spent my entire school and college life rebelling against. And suddenly, I discovered that all the [corporate] things I had sort of chucked out, were now required.

Battsek instead found work in Australia at The Hoyts Film Corporation, returning to the UK and landing at Palace Pictures in 1985.

At Palace, it felt like over 50% of the movies that we were involved with, involved Film4. It might not have been, but it felt that way. We were in sync with the profile of the filmmakers and the movies.

When I arrived at Film4, I had to buy into the strategy that David Abraham [Channel 4 CEO, 2010-17] and David Kosse had formulated, but was still relatively untried. In our industry, it’s always a balance between the heart and the head, between one’s subjective connection to particular projects and particular filmmakers, and [finding] a way of making those movies so that they have the maximum chance of being successful, both creatively and economically.

One needs to tread the path between loving all of our children equally, and also not pretending that there aren’t films that I will always look back on, and be especially proud to have been a part of. I’m proud to have been involved with filmmakers that have grown up within Film4, and see them making films that make bigger and bigger splashes. Yorgos Lanthimos and Martin McDonagh are clear examples of that. But I’ve had equal enjoyment out of Rocks and Saint Maud and Everybody’s Talking About Jamie. Oliver Hermanus’s Living is another film that I would put at the top of the list of films that I feel represent, maybe not quite the same edginess as some Film4 films have had, but an almost perfect realisation of what it set out to be.

It is the filmmakers who are responsible for those films, but we help create the environment and the wherewithal for those films to get made, and also to get out into the world. We are side by side with these films as they go from the very first pitch meeting through to the very last [financial] statement that comes in from whoever we’re in business with — that’s the role we play.

In 2020, Sue Bruce-Smith, who had worked at Film4 for 20 years, and was deputy director, died of cancer, aged 62.

So many things [underpin the admiration and respect she commanded]. She was incredibly knowledgeable, and experienced at a whole gamut of skill sets regarding development, production, finance, business plans, international sales and distribution. She was just a very smart business woman, who was also one of the nicest people you could ever wish to meet. Every filmmaker of every description would trust her with their life, and their film.

And she was also a brilliant colleague, both in terms of equal colleague, but also the people that worked for her loved her. The respect and love for her is as existent now as if she were still here. There’s no exaggeration in the influence that she continues to have over everything that we do.

1 Readers' comment