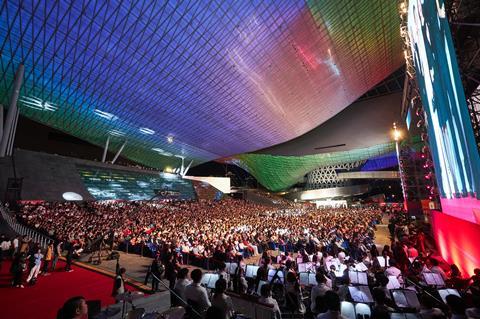

Celebrating its 25th anniversary, the Busan International Film Festival (BIFF) would normally have opened to crowds of fans cheering international stars and arthouse film directors alike on the red carpet at the Busan Cinema Center.

Designed by Austrian architectural firm Coop Himmelb(l)au specifically for the festival’s use, the centre’s renowned cantilever roof is lit up with rainbow-coloured LED light displays and opening night would traditionally also see a fireworks show in the South Korean port city.

But, like other festivals around the world, BIFF has had to contend with adjusting and mapping out ways to keep people safe in the Covid-19 global pandemic. Among other measures, the festival has opted to cancel its opening and closing night ceremonies, red carpets, midnight screenings (which would run all night) as well as outdoor talks and receptions – in addition to pushing its dates back a fortnight to run October 21-30.

“It was very hard to get a sense of the situation since it kept changing, but for us, Chuseok was important. We decided to wait until after the [two-week] incubation period and open on the 21st with the caveat that if there was another outbreak, we would cancel,” says festival chairman Lee Yong-kwan.

The harvest moon festival of Chuseok is traditionally a major migratory holiday for families to gather in Korea. Following the lunar calendar, this year the three-day national holiday fell September 30-October 2, and with the country at Level 2 in quarantine measures before that, many raised concerns that another outbreak could occur. Fortunately, the daily numbers of confirmed cases stabilised and South Korea’s government took the country back to Level 1 on October 11.

“But we decided to take it as Level 1.5 to 1.9 and prepare accordingly,” says Lee. “Regular cinemas can take 50% of their capacity and public buildings in Busan can take 30%, but we have decided autonomously to run our cinemas at 20-25% capacity.”

The festival also decided to hold its screenings solely in the Busan Cinema Center where they could guarantee safety measures, and also because the changeable situation made it difficult to plan ahead with the commercial cinemas such as the nearby Lotte and CJ CGV that BIFF usually works with. Even though it has downsized the selection from around 300 films in recent years to fewer than 200 this year, each film will only be able to screen once on the centre’s five screens.

“Fortunately, the screenings are spaced with an hour between them, so we can disinfect and air out the cinemas every time,” says Lee. “Masks are mandatory and we encourage audiences to wear KF94 masks. Temperature checks, QR codes [for contact tracing in case of infections], and distancing will all be upheld and we are asking people to only bring in drinks with tops and to drink quickly before putting their masks back on right away.” (Food was already prohibited at festival screenings before the pandemic.)

The festival will open with a socially-distanced world premiere of omnibus Septet: The Story Of Hong Kong, directed by Sammo Hung, Ann Hui, Patrick Tam, Yuen Wo Ping, Johnnie To, Ringo Lam and Tsui Hark, and video presentations.

According to the Central Disaster Management Headquarters and Central Disease Control Agency (recently upgraded from CDC Headquarters due to its activities in the face of the pandemic), South Korea has an accumulated 25,424 confirmed cases of Covid-19, with 84 new daily cases reported as of midnight October 20, and only 450 Covid-related deaths since January 3.

The country has managed to comparatively contain the pandemic using widespread, easily accessible testing and careful contact tracing along with quarantine measures and social distancing. This has all been achieved without a full lockdown.

“It’s different in South Korea. It’s seen as a great crisis to have 200 new cases a day,” notes BIFF programme director Nam Dong-chul, who says it helped with programming when Venice and San Sebastian opened amidst much higher case rates in their respective countries. “Distributors didn’t even want to show us films for a while before that because of the uncertainties.”

The selection

The final selection features 192 films from 68 countries, downsized from last year’s 299 films from 85 countries. Seventy are world premieres and 20 are international premieres, and titles include Venice award winner Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s Wife Of A Spy, Amos Gitai’s A Night In Haifa, Tsai Ming-Liang’s Days and Korean-American director Lee Isaac Chung’s Sundance award-winner Minari.

“A lot of new films came out of Asia,” says Nam. “They say the film industry is in an overall slump but we had so many Asian independent films and Korean independent films that we didn’t have any problem finding films to programme.”

Among these, Nam has noted strong first and second features from directors who have drawn attention in the past, such as Kim Ui-seok’s Empty Body, Lee Ran-hee’s A Leave and Lee Chungryoul’s Cicada.

The festival will close with Tamura Katoro’s Josee, The Tiger And The Fish, an animation remake of Inudo Isshin’s 2003 cult hit.

Busan will also be screening 23 of the 56 Cannes 2020 Official Selection titles that were announced in June but could not be screened when the French festival was cancelled due to the pandemic, among them Another Round, Soul, Ammonite and the opening film.

Meeting with audiences

Unlike some other festivals, Busan was not prepared to go online for screenings, although it will hold online Q&As and press conferences.

“We need to maintain our international reliability,” says Lee. “First of all, we asked filmmakers who were submitting to us whether they would consider online festival screenings and the overwhelming response was against the idea. So many of them are giving us their world and international premieres. So we decided we couldn’t do an online festival – that getting these films in front of audiences was tremendously important.

“[But] even if we couldn’t have foreign filmmakers present, we should have online Q&As with them, and have local filmmakers, who have been so depressed by the situation, meet with audiences in person.”

Although some international filmmakers with works in the selection even offered to pay out of their own pockets to go through South Korea’s mandatory 14-day quarantine upon arrival, the festival has opted not to host any overseas guests this year. Instead, they will have virtual attendance through pre-recorded presentations and live video-call chats with audiences who can send in questions through an online chatroom.

In total, 140 online Q&As have been scheduled including with Hara Kazuo (Minamata Mandala), Frederick Wiseman (City Hall) and Jia Zhangke (Swimming Out Till the Sea Turns Blue).

“If we operate the Busan Cinema Center with its roughly 20,000 seats for a full ten days, about one-tenth of the 200,000 tickets could be sold,” says Lee. “We don’t expect the maximum of sold-out screenings. Perhaps about 15,000 to 18,000 admissions.

“We’re operating without sponsors, [relying] solely on national and city funding with a budget of about KW7.6bn-7.7bn [$6.66m-$6.75m],” Lee continues. “We might save money because of all the events and guests we aren’t having this year, but the budgeting is more complicated as we used to use sponsorship funds for operating costs and we’re still in discussions with the Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism and Busan City as to what can be permitted.

“The Covid-19 pandemic doesn’t look like it will end easily. When we wrap this edition, we’re going to be looking at next year’s edition. We will have to be more active about online screenings – although, of course, maintaining offline screenings as a central part of the festival – and look to solving the issue of operating in the digital era, which we had already been thinking about for a long time.”

![The Brightest SunScreen[Courtesy HKIFF]](https://d1nslcd7m2225b.cloudfront.net/Pictures/274x183/3/5/0/1448350_thebrightestsunscreencourtesyhkiff_312678.jpg)

No comments yet