Jacques Audiard gets ever more adventurous with Spanish-language musical Emilia Pérez. Screen talks to the French filmmaker about his transgender Mexican odyssey.

Jacques Audiard has long been one of France’s more cosmopolitan directors. His 2009 prison drama A Prophet featured a North African protagonist rising through the ranks of a Corsican crime gang; his 2015 Cannes Palme d’Or winner Dheepan was about Tamil immigrants caught in a gang war. He has even ventured into the hallowed terrain of the American western, with his English-language The Sisters Brothers (2018). The filmmaker is breaking yet more new ground with Emilia Pérez, a Spanish-language musical that competed this year in Cannes, winning the jury prize and a collective best actress award for its four leads: Karla Sofia Gascon, Zoe Saldana, Selena Gomez and Adriana Paz.

Emilia Pérez — selected as France’s official entry for the international feature Oscar — is notable for its daring subject matter and format. The film is about a Mexican narco boss who transitions to a new female identity and attempts to redeem their criminal past by becoming a philanthropist. Shot on studio sets in Paris, the film contains 16 specially written songs and is performed in Spanish — this from a writer/director who concedes he does not speak the language. Emilia Pérez is produced by Pascal Caucheteux of Why Not Productions and Audiard and Valérie Schermann at the director’s own Page 114, together with Pathé France.

How did Audiard get his partners to board something so audacious? “I developed it myself at Page 114,” he says, “and that took about two years. My company produced the music and songs, and we developed the script. Once that was done, I went to see Pascal — and the film started to move ahead at that point.”

The original spark was Boris Razon’s 2018 novel Listen (Écoute), which Audiard read during lockdown; fascinated by the very brief appearance of a narco who wants to transition gender, he decided to pursue this character further. The filmmaker has described Emilia Pérez as “operatic” — and, indeed, the original idea was for a staged opera. “I came up with a treatment, some 30 pages, which I wrote very fast, divided into acts. The result was an opera libretto.”

Early on, Audiard discussed the project with musicians Tom Waits, Damon Albarn and Gonzalez, but the job of putting Emilia’s story to music finally went to French composer Clément Ducol, whose scores include Francois Ozon’s Peter Von Kant and the animation Chicken For Linda!. “It took a while before we considered that this could be a film,” says Audiard. “I asked Clément, ‘What are we doing exactly? Is it for the stage or for the cinema?’ He said, ‘It’s for the cinema’ — and, from that moment, it was.”

The lyrics were provided by Ducol’s partner Camille Dalmais, known simply as Camille, a popular but experimental singer/songwriter feted for her 2005 breakthrough album Le Fil. Dalmais did not speak Spanish at the time, so worked closely with a translator. “She started by writing French lyrics,” says Audiard. “She’d try them out, get them translated, then rewrite them, and so on. And now she speaks fluent Spanish.”

There was never any doubt about the film being in the Spanish language, says Audiard. “The story involves a Mexican cartel boss, it comes out of the Mexican universe. So there’s no choice. Are you going to have them sing in English, with American accents? I didn’t want that.”

Power of four

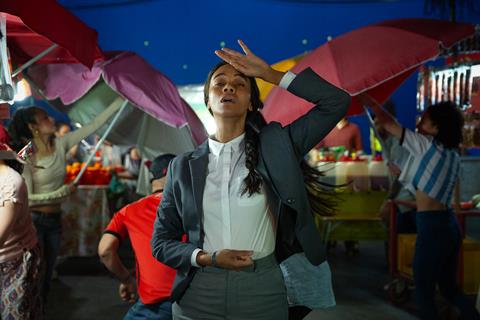

The film’s lead quartet included two actresses with heavyweight international profiles. Saldana, who plays lawyer Rita, became a star through the Avatar, Star Trek and Guardians Of The Galaxy film franchises, but began as a dancer, trained in her native Dominican Republic; her first big-screen role was as a ballet student in Nicholas Hytner’s Center Stage (2000). A key part of Emilia Pérez was Saldana’s work with choreographer Damien Jalet on some highly demanding dance sequences.

As for Selena Gomez, currently starring in TV’s Only Murders In The Building, Audiard had seen her in Harmony Korine’s Spring Breakers and Woody Allen’s A Rainy Day In New York, but was unfamiliar with her parallel career as a recording artist.

Emilia’s lover Epifania is played by Mexican actress Adriana Paz, whose work includes films Perpetual Sadness (La Tirisia) and The Motive (El Autor) and TV series Coyote and La Rebelión. And in the central role of Emilia, there was the decisive casting of Karla Sofia Gascon, a Spanish actress who for several years was based in Mexico; she established a prominent film and TV career in Spain before coming out as trans in 2018.

“If I hadn’t met Karla Sofia,” muses Audiard, “how would it have been? There’s no answer to that.” Gascon’s own history gives her performance as Emilia a particular authority. “I think it allowed her to completely absorb the character,” says the filmmaker.

“When I was thinking about trans identity, I’d ask Karla and she would give me the answers. There were scenes I was hesitant about filming, and she’d tell me yes or no, or how to do it. She’s incredible — her personal history makes her very specific as an actress. That’s how she is, because that’s where she comes from.”

The director recognises he has undertaken a thorny subject that was likely to be controversial: some commentators have argued that, being himself neither Mexican nor trans, it was presumptuous for Audiard to make the film. He argues that, for him, the film’s trans and Mexican themes are closely linked. “Mexico has the same problem faced by three or four countries in Latin America — the collapse of democracy, the invasion of narco trafficking.” But he adds, “We shouldn’t be too smug in France, either.”

“When I first had the idea, I immediately thought, without quite being able to pin it down, about the idea of a person who wants to transition and a country torn apart,” says Audiard. “If a country is torn in two, how can it be reunited? Maybe it takes someone like Emilia who makes this huge leap forward, then looks back at all the harm she’s done. Maybe she’ll have ideas, and maybe those ideas are good — whether she’ll succeed is another question.”

While he originally entertained the idea of filming on location, Audiard came to realise that a studio-based shoot was essential for creating the stylisation he needed. Among the musicals that informed Emilia Pérez, he lists Jacques Demy’s The Umbrellas Of Cherbourg and Bob Fosse’s Cabaret. “It’s because they’re political films. And yes, you can have political musicals — like Evita, which I like rather less. Another that I like a lot is Chantal Akerman’s Golden Eighties — I took a lot of inspiration from that.”

A key collaborator was art director Virginie Montel, who was in charge of the film’s overall look, including sets and costumes (she has been Audiard’s costume designer since Read My Lips in 2001). “Virginie shows me a lot of images, for the characters notably, and I’ll maybe pick up on a particular detail — and, based on what we both think, we’ll create a synthesis together.”

Cinematographer Paul Guilhaume, who shot Audiard’s last film Paris, 13th District, already had musical experience shooting videos for Kanye West and Beabadoobee. “Paul is a young DoP and he brought the kind of light sources with him that just weren’t around when I started —LEDs and all that, crazy stuff. I asked him to make the lighting changes very visible — obviously you can’t overdo it, but we did it a lot.”

Tough start

A key moment in the shoot, says Audiard, came at the start, filming Rita’s number ‘El Alegato’. “It was the very first sequence we shot — it took maybe two, three days. I thought, ‘Let’s start with the hardest thing’ — it’s a very complicated sequence, which uses the entire space of the set, the greatest number of actors and extras. And as soon as we’d done that, I thought, ‘That’s it, it’s working.’”

Emilia Pérez has attracted 1.06 million admissions in France since its release in August; in the US and UK, it had a limited cinema release ahead of Netflix’s November 13 streaming launch. Despite having earned four nominations at the Bafta Film Awards, all for film not in the English language, and winning with The Beat That My Heart Skipped and A Prophet, Audiard has yet to earn any attention from Oscar — a situation that may now change with a film that reflects the ever-expanding scope of his cinematic ambition.

“I felt cramped by French cinephilia, which endlessly refers back to the New Wave,” he says. “I have nothing against the New Wave, but it makes for a way of thinking that to me feels limited. I want to reach the greatest number of viewers — and not necessarily in my own language.”

Jacques Audiard breaks down three musical numbers from Emilia Pérez

‘El Alegato’

Lawyer Rita, who has successfully exonerated her guilty client, begins a song that segues into a grand procession through the streets of Mexico City

“Our actresses didn’t all have the same abilities, choreographically speaking — they weren’t all dancers in the same way. The big challenge for Damien Jalet was to adapt his choreography to each of them. In particular, he worked with Zoe because she had so much to do. Her main numbers, like ‘Alegato’ at the start of the film, are really difficult. These songs have a lot of dynamism, and they use a lot of space. Zoe had a lot to do, and she’s incredibly gifted. I think Damien loved working with her.

“‘Alegato’ means ‘legal plea’. It’s a prologue introducing us to Rita as an attorney — it’s about her complexity in relation to her work and to morality. The lyrics came very quickly, but it took a while to find the right music and rhythm. Then I had the idea of bringing the Mexican world into it, bringing the Mexican people in behind Rita, as if on stage. She’s surrounded by a crowd, and they’re all responding to her like this [claps rhythmically].”

‘La Vaginoplastia’

Rita learns about male-to-female transition surgeries

“I had two models for this. One was Hair, a film I like very much — that was the musical reference. And, for the image, it was a mix of [Chantal Akerman’s] Golden Eighties and Busby Berkeley. It’s a difficult song. When you try to direct a number like that, with all the choreography that goes with it, you wonder, ‘Is this going too far? Is it going to be ridiculous?’ That’s not the right attitude. In a way, the piece itself told me how far I could go. The film is about going all the way — you have to accept there’s an element of kitsch to it, an element of telenovela, you have to accept it goes over the top, and you have to let yourself be naïve, vulgar, all of that. Sometimes I get nervous about doing that… but here I could.”

‘Las Damas Que Pasan’

Epifania dedicates this crescendo-building, choir-backed song to the one she loves

“This is based on ‘Les Passantes’, a song by [20th-century French singer/songwriter] Georges Brassens. Years ago, [screenwriter] Thomas Bidegain played me an instrumental version by a Cuban orchestra, and when we were looking for music for the end of the film, that’s what I thought of. The musicians liked it, and Camille wrote new words. It’s the moment when Emilia becomes a sort of saint, Mexican-style.”

No comments yet