As the BIFAs shrug off their teenage years, change is on the agenda. Co-directors Amy Gustin and Deena Wallace talk to Screen about turning 20 and the awards’ boldest step yet.

When Johanna Von Fischer and Tessa Collinson announced in 2014 they were stepping down from the British Independent Film Awards (BIFA), Deena Wallace was one of the first to contact Raindance Film Festival topper and BIFA founder Elliot Grove to register her interest.

Coming to the end of her maternity leave at Bafta, where she was head of film, overseeing adjudication and voting for the annual film awards, and having worked for both Raindance and BIFA in the past, she was ready for a new challenge. Grove was keen to welcome Wallace back into the fold, but was already talking to event organiser Amy Gustin; would the pair be willing to run the awards together?

“We’d never met,” recalls Wallace, sitting down with Screen International at BIFA’s tiny office in Raindance HQ near Charing Cross station. “We had no idea if we had the same aspirations for BIFA. We had lunch and figured out that we had the same vision. It’s an incredible fluke that it worked.”

Adds Gustin: “Deena has lived and breathed awards shows. I came at it from event production and working with cinemas and film releases. It worked well that we had totally different skillsets.”

The pair’s first task was to solicit input from a range of voices in the UK film industry, discovering affection and goodwill for the annual awards ceremony, but also little understanding of the way BIFA worked, especially with regard to the nominations process and who got to vote. Within craft industries, there was frustration about BIFA’s policy of bundling all technical categories into a single award, which saw production designers and casting directors compete with editors and composers. From distributors, there were laments about the power of the BIFA brand in the public realm — winning was nice, but could the accolades be leveraged to drive audiences?

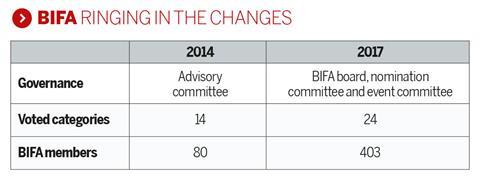

In other words, there was plenty of work to do and — a perennial challenge for BIFA — limited resources with which to do it. Determined to expand the base of voters, or members in BIFA speak, Wallace and Gustin initially invested in an online voting platform that was fit for purpose. “The easiest thing to show people how BIFA works is to let them be part of it,” explains Wallace, “but we didn’t want to invite loads of people to be new BIFA voters, only for the website to crash and for us not to be able to cope with it. We had to do it step by step. We’ve gone from 60-odd voters when we took over to 200 or so voting this year.”

Member state

To expand the voter base, BIFA invited past nominees and winners who were not yet members, and reached out to practitioners in fields where membership was poorly represented. Aspiring members can now apply via the BIFA website, and there is a procedure in place for approvals. An additional 200 BIFA members participate in the awards only at the final stage, picking the winners of two categories, bringing the total number of potential voters to 400.

While that change was highly visible to UK industry, the pair also made some important structural changes. Previously, there was a BIFA advisory committee that had rather vague powers. Now, BIFA has been set up formally as a non-profit organisation, regulated by a 10-person board of governors who must approve the annual budget and strategic goals. Members include Grove, Raindance programmer Suzanne Ballantyne, Lionsgate UK CEO Zygi Kamasa, filmmaker Sarah Gavron, Think Jam CEO Daniel Robey and veteran film publicist Charles McDonald. Two new committees — one supervising the event, the other the nominations process — make a range of decisions.

In the pair’s first two years, they refined the awards’ focus on new filmmaking talent, creating categories for debut screenwriter and breakthrough producer to join debut director. The Raindance Award, celebrating the best British film playing at that year’s Raindance Film Festival, was an anomaly that was long overdue for reform (BIFA members did not participate in the nomination choice, and neither did the BIFA jury pick the winner). It was replaced in 2015 by the Discovery Award, sponsored by Raindance, for innovative filmmaking achievement at budgets below $660,000 (£500,000).

The biggest change to the awards has come this year: replacing the single technical achievement award with individual categories for casting, cinematography, production design, costume, hair and make-up, sound, editing, music and effects. This had long been an ambition at BIFA, but there were reasons for trepidation. “We were nervous of not being able to give proper recognition to those categories,” says Wallace. “We knew that it would be really hard for us to have all those extra nominees at the show, because it would cost tens of thousands of pounds that we just don’t have. It squeaks by each year.” Adds Gustin: “Also the logistics. We don’t want to sit there for four hours. People like the fact the ceremony is short and sweet.”

While the pair worried these nominees might feel insulted if they were not included at the ceremony, the nominations committee took a different view. The compromise solution has been to introduce a new, sponsored nominees party at Kettner’s Townhouse for all off-camera talent, which will include all the technical-category nominees. Winners of the nine technical categories will be announced on November 23, and will attend the BIFA ceremony on December 10, where a clip reel will showcase the winning work. “But we’re not going to troop everyone up on the stage like a school prizegiving,” says Wallace.

In future, the pair hopes this scenario will evolve into something bigger and better for the technical categories, but, explains Gustin: “In the first year, it’s important to get the mechanics of it right — to make sure that we are getting the right nominees through and the right trade coverage, and it is making a difference to those nominees.”

While Bafta Film Awards craft categories have often been dominated by US productions, BIFA hopes these new nominations will create a platform for technical achievement in British films. “It will be interesting to see how that plays out, to see how often it’s used in campaigning emails that are sent to Bafta voters,” notes Wallace.

Traditionally, BIFA has limited the role of its members to the nominations procedure, while a jury — latterly, juries — picked the winners. Last year, the winner of the best British independent film was voted on by the entire BIFA membership, instead of by the main jury, and in 2017 the same will go for short film. One upside of this is that the five nominated shorts will be viewed by up to 400 voters — vital exposure for the work.

Jury’s not out

As the BIFA membership continues to expand year by year, it is easy to envision that these voters will play a steadily expanding role, picking winners for a growing field of categories. “I think there are certain categories where that could work and there are others where the jury process is really valuable,” cautions Wallace. “Particularly where you are looking at new talent, where you are looking at promise and potential as well as achievement. And we don’t yet have the same set-up as Bafta where our voters are sent DVDs, invited to screenings and treated like kings and queens. It still is, in certain cases, a battle to get the films seen.”

While Wallace and Gustin have succeeded in making important category reform and creating greater transparency by inviting more and more practitioners inside the BIFA tent, there is still work to be done when it comes to broader public engagement, despite experiments including BIFA Meets (live interviews with talent such as Brendan Gleeson and Michael Sheen), public screenings of BIFA-nominated films, and this year’s BIFA Independents scheme — monthly BIFA-branded screenings of relevant films at Vue, Odeon, Everyman and Curzon.

“There is a gap for an organisation as influential as Mercury in music or the Booker in literature to support independent film, and that is the spot we think BIFA should be filling and can fill,” says Wallace. “We have the authority, based on our voters and the rigour of that process. What we are not necessarily doing is influencing people with those selections yet. So for us there’s a big brand-building exercise to do and finding exactly the right position, the right way to make itself available to films and filmmakers to best support them as they release.”

With 2017 marking the 20th BIFAs, an opportunity exists to cement the awards as a tastemaking brand, which the organisation is determined to exploit. “We’ll have 20 winners of best British independent film, and we’re planning to highlight the films that we’ve recognised in the past,” says Wallace. “When you see Moon and Control and Monsters and films that you love linked to BIFA, then the next time we come up with a list of films, you go, ‘OK, they liked those ones so we can probably trust them.’

“This is a matter of us figuring out what we can do for no money. So it will be an online social-media campaign that uses lots of our content and makes the most of the history and legacy of the awards.”

The 20th BIFAs will be held on December 10 and the nominees party on November 22. Charles Gant is a member of the BIFA nomination committee.

This feature first appeared in the November issue of Screen International. Click here to subscribe.

![The Brightest SunScreen[Courtesy HKIFF]](https://d1nslcd7m2225b.cloudfront.net/Pictures/274x183/3/5/0/1448350_thebrightestsunscreencourtesyhkiff_312678.jpg)

No comments yet