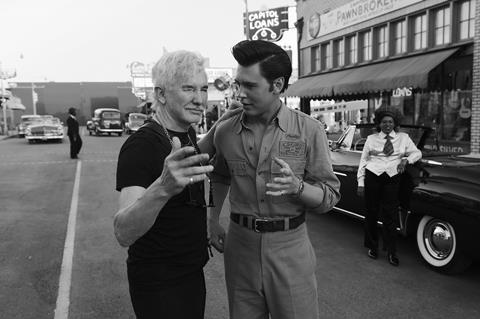

Elvis filmmaker Baz Luhrmann and star Austin Butler bonded through an extended casting process, Covid lockdown in Australia, the film’s eventual shoot, and its long aftermath since Cannes last year. The pair talk to Screen.

When director and co-writer Baz Luhrmann conceived his biopic Elvis, he envisioned it as an Amadeus-like epic about a petty little man, Colonel Tom Parker (played by Tom Hanks), who narrates the story of a far greater talent, the superstar singer he would help bring to prominence — Elvis Presley. “His gift is not song,” Luhrmann says over Zoom from Los Angeles about Parker. “His gift is the sell.” Luhrmann’s artistry, of course, is that he combines the gifts of both men: he makes films full of song and energy and movement, proving to be the ultimate showman.

Since its rollicking debut at last year’s Cannes Film Festival, Elvis has been one of the few non-franchise films of the pandemic era to lure adult audiences back to the big screen, grossing $287m worldwide for Warner Bros. It has also earned eight Academy Award nominations, including best picture for Luhrmann and his fellow producers (who include creative and life partner Catherine Martin), and best actor for Austin Butler, a relative newcomer so determined to land the title role that he consumed himself in research, refusing to take any other auditions during the casting process so that his focus was not diluted.

In mid-February, Butler took time out from being feted at Santa Barbara International Film Festival to join his director on a video call to discuss the sometimes-bumpy road travelled to make Elvis a reality. But where Presley and Parker often clashed, Butler and Luhrmann enjoyed a harmonious rapport that continues to this day, their conversation filled with laughter and happy memories.

After the two of you first met, it took five months before Austin was cast officially. Was that time spent convincing Warner Bros that he was the right person to play Elvis Presley?

Baz Luhrmann: I can probably force anyone’s hand on almost any subject because one carries a certain amount of weight, but I never want to do that. I want to believe that, through process, I’ve got everyone believing [in my vision], because if everybody believes then we’re all collectively going down the same road at the same time. I can say now that the moment Aus came in, he was down the Elvis road — he was simultaneously very humble, very sensitive, but incredibly focused. I remember in the workshop process going, “Everything’s great, but what is the depth of Austin Butler’s ability to tap into rage?” I got this little scene we scribbled up where [Presley] confronts the Colonel down in the garage. Austin had the idea he might have a gun on him — Elvis would pull guns now and then — and I think I gave Austin a brush or a comb…

Austin Butler: It was a hairbrush.

Luhrmann: A hairbrush! It was terrifying — the level of rage [Butler showed], it was like, “Okay, we’re good here.” When Priscilla [Presley, Elvis’s ex-wife] saw the film, she wrote to me: “It’s one thing to have copied exactly the movement, the subtlety, the finger scratching the nose when he talks, but how did Austin know Elvis’s rage? How did he tap into Elvis’s stillness?” That was a process — two-and-a-half years of process.

No matter what I threw at Austin, he would handle it, and this was about preparing him for the gargantuan mountain he had to climb, because it wasn’t just that he was going to have to climb it in terms of the craft of acting and finding Elvis. We tried to keep it all a secret, but you’re casting the role of Elvis Presley — Aus, you had to face a lot of people, like when they cast the new James Bond. Austin, I question you, whether you blocked that noise out or whether that ever distracted you or gave you more pressure.

Butler: I’m not going to lie to you that that voice wasn’t there. I feel it every time I do anything creative — a voice that says, “You are incapable of this,” or, “You are not good enough.” I think that’s the sort of fear that sharpens your focus, so this process was such a practice in being able to hear that voice but turn down the volume as much as I possibly could. Otherwise, you’re crippled — you don’t want to get out of bed in the morning.

Luhrmann: I never told you, but I can be blunt about this. I was on socials early on [in the making of Elvis] because I knew that I wanted to communicate directly with the audience, and when I cast Austin, my feed was just jammed with three letters — WTF. Some of the comments moved towards — I wouldn’t say death threats but, seriously, to the level of, “What are you thinking?” People forget that when I started out with Leonardo [DiCaprio] on Romeo + Juliet, people could not have conceived that one day he would become the Leonardo we know today.

Austin, when production shut down after Tom Hanks got Covid, you opted to stay in Australia, convinced the film would still happen. But where did you stay? I like imagining you moving in with Baz and Catherine.

Luhrmann: He [stayed in the] broom cupboard underneath the stairwell to my house. He loved it! [laughs]

Butler: I was Harry Potter underneath the stairs! [laughs] No, I stayed in the same apartment that I was living in before. The wild thing was, when force majeure was called on the film, there is no contractual obligations anymore.

Luhrmann: Including paying people.

Butler: Yeah, I had been preparing for a year at that point. I had to make this decision — am I going to, essentially, move to Australia right now and pay for my own apartment? I just treated it like, “Well, I would have to find a place to live in LA anyway, so I might as well pay for my apartment here in Australia and just treat this as a time of freeform exploration.” It then became a lot more — it was less of a curriculum way of working and more just every day waking up with my heart beating out of my chest and [going] towards whatever I was either scared of or fascinated or curious about.

It was the early stages of Covid — how did you two stay connected?

Luhrmann: One thing I’ll always cherish is we decided to have a film club. We would all get on the Zoom, dress up, and we had a hat — we all put in it a film that we didn’t think the others had known. We watched the movies, and we would discuss and debate, and this kept morale going.

It was visionary that [Queensland premier] Annastacia Palaszczuk locked the state down. [After a period] we could live a normal life, pretty much — there was a bit of wearing masks, but we were now free. Aus, we started taking some walks to catch up — do you remember?

Butler: I don’t remember how many months it was where we didn’t see each other at all — that’s when we had the film club. I would leave the house to go for my walks on the beach. The first time we saw each other, we went surfing together.

Luhrmann: Wasn’t that fun?

Butler: That was amazing.

Luhrmann: We got boards and we took lessons and we sat on the beach. It was awesome.

Butler: That was the first time we saw each other in person after a couple of months of being apart. At that time, there wasn’t this looming pressure of “the film’s about to start”, so then I got to go back and reread the books about Elvis. Then you and I were sending ideas back and forth. You would send me new scenes that you’d written.

Luhrmann: Yeah, I was rewriting the whole first act, actually.

Butler: I got to see how your mind used that time to create the film that is now in the world. You had already been working on it for so long, but I feel like things clicked into place. I am grateful for the time that we had.

Luhrmann: Many breakthroughs [came] from us working together. It was a beautiful, unique parallel universe whereby a director and an actor were caught in this nether area where they could just absolutely not be distracted by the budget or other pressures and just be talking about story and character.

Elvis is not just about Elvis Presley — it is about the US at a very specific moment in its history. Baz, you grew up in Australia, and Austin, you were born after Elvis had died. In a sense, did you both approach this topic as outsiders?

Butler: We talked a lot about that time because of all the parallels that were happening [today]. The news would be on — there would be a riot somewhere, and then you would be seeing the riots that were happening in the ’60s. That made it just feel incredibly poignant.

Luhrmann: I surrounded myself with young researchers — they were integral. [They are] connected to — I’m going to avoid the word woke — a new wave of awareness about history, awareness about what was actually the ’50s, ’60s and ’70s. The ’50s were an incredible burst of newness and energy and the beginnings of dealing with race in [the US] — [the researchers] kept me on point about part of the reason to do this movie was these issues have not gone away.

[Research assistant] Jack [Flynn] would be spending so much time counter-arguing, trying to punch holes in the Elvis [mythology] — not to bring him down, but to be clear about what was going on in America [at the time]. There’s no way we could tell this story without telling the story of America. It’s what Austin said — yes, we were examining America in that period, but really, we were looking at the America we were living and breathing in right as we were making the movie.

Did your views of Elvis ever differ so that you would have to come to some sort of compromise?

Luhrmann: Aus, tell it from the heart, but I honestly do not remember anything like that. I remember the opposite, which was Austin would tell me something he had read, and I would go, “Oh, I hadn’t read that. Yes, and what about this?” We were only ever doing the, “Yes, and…” game, which is, “Gee, that’s great — that reminds me of…” I feel like we were two kids on a treasure hunt.

Butler: I always say this when I’m not in your presence, but when people ask me about what it is like working with you, that’s one of the qualities that I admire so deeply — I never heard you say no to anybody.

If it was the hair and make-up team or [cinematographer] Mandy [Walker] or one of the actors — if somebody had an idea, I would never hear [no].

He may just take a sliver of what they’ve said, and it will lead into this brilliant thing. He is able to find the good in what everybody’s ideas are — you never feel like your hand is going to be slapped for an idea.

I could say, “I read this scene in a book, and I don’t know where it could possibly be in the film…” You’re trying to encompass somebody’s entire life, and I just would find a little moment. Baz would say, “That energy is amazing, maybe we can put that in this scene” — and, suddenly, now you enrich something.

Luhrmann: Aus, I don’t know if I ever said this on the set, but I call that “the third idea”. It is part of the process for me. Someone serves, and then you listen and you do a positive serve back, and you serve a couple of times. Generally, a third idea rises up that neither of you actually had — it’s a combination of both. It’s tennis and you’re doing a volley — suddenly, the ball goes up in the air and flies by itself.

No comments yet