NFTS students have been making short films as part of their learning since the school’s inception, many earning plaudits from Bafta, Oscar and international festivals. Screen selects 10 of the best shorts across animation and fiction, and talks to the directors about their filmmaking journeys.

Fiction shorts

Caprice (1986)

Dir. Joanna Hogg

Hogg’s graduation film Caprice – full of 1980s colour, music, dancing and fashion – is not an obvious calling card for the sensitive, quieter dramas she went on to create. “I was having a typical early-20s identity crisis around who I was and what I looked like,” she recalls. “The film is exploring my love of fashion and Hollywood musicals and also the pressure of looking a certain way. I was aware even back then the film would be full of love and joy for something, but a darkness around it as well.”

Tilda (then credited as Matilda) Swinton stars as a woman obsessed with a fashion magazine who sees a more complicated side when the publication’s sections and articles come to life. Hogg says that watching Godard’s 2 Or 3 Things I Know About Her “emboldened me to be playful but also talk about something serious”.

Swinton and Hogg had known each other from school and had collaborated on a previous NFTS project of Hogg’s that was never completed. “The whole question of identity and interest in fashion were themes and issues that we both shared. It was a real joy to work with her,” says Hogg.

Of course, Swinton continues to be an important Hogg collaborator, appearing alongside her daughter Honor Swinton Byrne in the director’s two latest features, The Souvenir and The Souvenir Part II. Those films are loosely autobiographical and revisit the tumultuous time in her life when Hogg attended the NFTS.

“I found myself completely immersed in that world again, that was interesting,” she says of her recent work. “I don’t think I’d be doing what I’m doing now without attending the NFTS. I was still shaping my thinking back then, and the film school was challenging me a lot. I needed that.”

Hogg recalls that her tutors “saw and understood what I wanted to do, even if it was very different to what other students were doing, more stylised”. She adds: “They were very supportive but I wish with hindsight I’d opened up more about what was going on with me personally, and allowed them to help me more.”

Hogg is full of praise for her collaborators on Caprice, including her co-writer David Gale who “helped me make something more incisive”, production designer Tom Cairns who “completely understood what I was trying to do” and cinematographer David Tattersall. “He trained at art school, so had an interesting sensibility,” she says.

Cairns, who was working in operas at the time, has gone on to direct his own films, while Tattersall went on to work with the likes of George Lucas. The team had the luxury to shoot the film over four weeks (in fits and starts) at the school’s soundstages and briefly on location at a newsstand in Covent Garden. Nick Thompson edited the film and he and Hogg continued to work together after graduation on music videos and commercials.

Like many filmmakers with their student work, Hogg says she is now “slightly embarrassed” by Caprice. “It’s so naive in a way. Even shortly after I made it, I wished I had connected the story somehow to reality more. But at the same time, it was quite a thing to pull off at that time.”

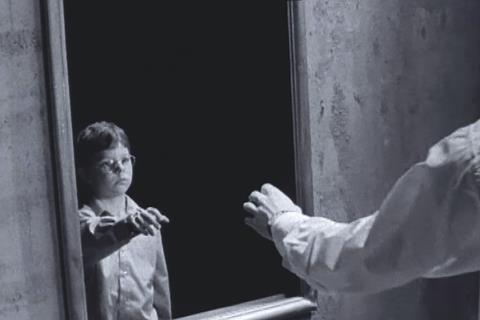

Madonna And Child (1980)

Dir. Terence Davies

Davies released his first short film Children in 1976, backed by the BFI. It was only after he was accepted at what was then the National Film School that he thought of continuing his protagonist Robert Tucker’s story with his second short Madonna And Child, which became his graduation film. He completed the trilogy after graduation with Death And Transfiguration in 1983.

Madonna And Child follows a now-middle-aged Robert as he struggles to reconcile his Catholicism, family duty and work life with his closeted homosexuality. “I was only accepted to the NFTS after my second application, and it was then formed in my mind that I wanted to do a little trilogy,” says Davies.

“The trilogy is really about despair. I was working through that spiritual angst. I realised I was gay when I was about 11, and because I was a devout Catholic I was praying on my knees to be forgiven.”

As with Children, he shot Madonna And Child in Liverpool, in less than three weeks and on a “very small” budget. “Thank goodness the crew was very sympathetic to the material,” says Davies.

He found it an interesting life lesson when he was shooting the film in the office space where he’d previously worked and gotten along well with the office manager. “During the shoot, they were incredibly hostile to me, and that was hurtful, but it was one actor who said to me, ‘It’s obvious why, you’ve gotten out [of office drudgery in Liverpool] and they haven’t.’”

The film does include some graphic scenes, such as the view of one man clutching another’s buttocks as he performs oral sex. “Shooting that scene of the buttocks, it was funny that I was the only one who was embarrassed,” recalls Davies. “I remember thinking, ‘Why did I write this?’”

The themes of the film and its explicit moments did raise a few eyebrows at the NFTS. “There were one or two staff members who thought it shouldn’t have been made,” he says. But most staff and pupils were very supportive of his vision.

Davies remembers only one “row” about the film – Colin Young, school director at the time, told him he should remove a stylish shot of Robert on a moving iron bridge at the end. “I hit the roof and went home full of indignation,” Davies recalls. “But on the way home I realised that he was right, I was being seduced by it being a good shot, not because it added to the story. I apologised to Colin and that was a good lesson for me – if you’re seduced by how good it looks you should probably get rid of it.”

After 1983, festivals tended to programme the films as a trilogy, and Davies remembers some very mixed reactions along the way. “One journalist in New York wrote, ‘These films make Bergman look like Jerry Lewis,’ which I guess is in some ways a compliment,” laughs Davies, who doesn’t rewatch his earlier films but says he learned a lot during the making of the trilogy. “My feelings towards my work are always ambivalent. I am conscious only of the mistakes. Being a Catholic, we can’t enjoy anything!”

He does, however, enjoy looking back at his studies at NFTS. “I had a lovely three years, and I was so lucky to get accepted on that second application. I don’t know what I would have done if I hadn’t gotten in. So many people were good and kind to me.”

Slap (2014)

Dir. Nick Rowland

Rowland’s Slap earned him Bafta and BIFA nominations and landed him an agent – not bad for a first-year short.

The film stars Joe Cole as Conner, a teenage boxer who likes to experiment with female attire and make-up. “I’m interested in hyper-masculine environments, and what you feel like if you don’t fit those expectations,” says Rowland, who continued to explore similar themes in his debut feature Calm With Horses (2019).

He co-wrote Slap with fellow student Islay Bell-Webb, who recalls they worked on about 20 drafts of the script. “I had to flesh out the characters we had, in particular Conner – to dig into the reality of being that isolated, being trapped by the gender you’re assigned at birth and flailing around for something else, without the language or resources to articulate what you’re going through,” says Bell-Webb.

“To me, a queer non-binary person who was grappling with my gender identity at the time of writing that script, it was a very personal mission, to make sure that Conner’s struggle was emotionally authentic.”

They had a challenge to shoot the 24-minute film on 16mm in just four days and with only five rolls of film. The shoot was in Slough, near the Mars factory. “We could smell caramel all the time,” laughs Rowland. But Slough proved convenient because they could move quickly between locations. “It was a location that had a lot of different options for us.”

Rowland says he “owes a lot” to Cole, who he met at Cambridge’s Watersprite Film Festival. “He was so supportive and was also generous to introduce me to his agent.”

Attending the 2015 Bafta Film Awards at London’s Royal Opera House off the back of Slap’s nomination, Rowland recalls the experience as “so surreal… We were film students out on the Sunday night, we bumped into our heroes, we had such imposter syndrome. The next day we were back in school having lessons. It was a special experience.”

Rowland made two more shorts before leaving NFTS: Sundance-selected Out Of Sight (2014) and graduation film Group B (2015) starring Richard Madden. He is especially grateful for the mentoring he received from Ian Sellar and Brian Gilbert.

“I still have all of my notes from their classes, anytime I am shooting I revisit those notes the night before,” Rowland says. “The day before the shoot of Calm With Horses started, they both called me and gave me a pep talk. I was shitting myself so it was great to have their words of support. They don’t have to do that. They really care, and you feel that even after you leave the school.”

Small Deaths (1996)

Dir. Lynne Ramsay

Ramsay was studying cinematography at the NFTS when she made the unusual choice to direct, not just shoot, her graduation film Small Deaths.

She came to the school after working as a still photographer – “which is in some ways more like directing than cinematography,” she reckons. She pushed to direct the film – “I was dogged about it, and they [NFTS heads] gave in after I annoyed them for three years,” she says with a laugh.

Ramsay had been writing short stories since she was a child and that inspired Small Deaths, which is a triptych of vignettes: a young girl witnessing trouble in her parents’ marriage; two girls seeing a group of boys abuse a cow; and a teenager being let down in an early romance. “It’s all these tiny moments in a girl’s life growing up, the disappointment in humanity,” Ramsay explains.

Ramsay didn’t want to shoot a more obvious narrative story as a typical calling card – “that felt phoney to me, if it was purely an exercise to get a gig later. I wanted to follow my instinct a bit more, I was embracing the short form and I love short stories.”

With an even smaller budget than the directing students, the film was something of “a homemade thing that my family helped with”. Ramsay cast her niece and brother and shot one sequence in her mother’s house.

“We had hardly any time to shoot, and I did no coverage at all – one scene just had two shots,” she recalls. “Everyone said, ‘You won’t be able to cut this.’ But I said, ‘Yes, it will work.’ They were pleasantly surprised when I made it work.”

At the graduation showcase, producer Gavin Emerson saw the film and acquired it, and then submitted it to Cannes; Ramsay thought that was a crazy long shot – it went on to win the jury prize. “It was at the time when the main jury would watch the shorts as well, and the jury president was Francis Ford Coppola,” says Ramsay. “To be a student and come into that environment and win the jury prize from Coppola, that totally blew my mind.”

During her time at the NFTS, Ramsay veered beyond her course, also attending sound classes, workshops about working with actors, documentary sessions, animation classes and much more. “It was like having a toy box to play in,” she says. “It’s an amazing school.”

Small Deaths production designer Jane Morton, editor Lucia Zucchetti and DoP Alwin Küchler (who shot the film’s third sequence) went on to collaborate on Ramsay’s Ratcatcher (1999) and Morvern Callar (2002). “Those relationships were so important to me,” she says. “When Derek Jarman came to the film school, he told us, ‘Filmmaking’s hard enough, I have to work with my friends.’”

Looking back on Small Deaths today, Ramsay says: “It is its own little oddity, but I think it captures these little moments. There was a purity to it.”

Still (2001)

Dir. Joachim Trier

Norwegian director Trier was only 23 years old when he entered the fiction directing course at NFTS.

“I grew up in a film family, and I had filmed my whole life, making skate videos and things like that,” he says. “I came in with a sense of visuals, but I was nervous about directing actors, and the NFTS was such a great place to learn about that tradition.”

His first NFTS short was 2000’s Pieta, which earned him international attention. For his second short Still, he recalls: “I was 25 and I wanted to put everything in one short film.”

The film shows a man at the end of his life looking back on past relationships and moments. “We wanted to go between the different spaces in the mind of this dying old man, rambling through notions of time and memory,” says Trier. “I wanted to emulate the stream of consciousness like in the great novels of Marcel Proust or James Joyce.”

Still was unusual in that Trier didn’t collaborate only with NFTS students, instead working with two friends back in Norway, co-writer Eskil Vogt and editor Olivier Bugge Coutte (the trio still work together frequently, most recently on this year’s Cannes title The Worst Person In The World). “Still is a great example of Eskil, Olivier and myself being stupidly ambitious but learning a lot together.”

He recalls with a laugh, “We used all available stocks from Fuji and Kodak at the time to give each scene its own identity. Still played at festivals including Clermont Ferrand, but wasn’t as award-winning as Pieta.”

One thing better than a gong was that one of his filmmaking heroes, Nicolas Roeg, came to the film’s screening. “He found it fun and playful and gave me some great advice,” Trier says.

While the trend in the UK at the time was to explore more gritty realism and humanist storytelling, Trier was immersing himself in watching stylised cinema, which shows in the shorts he made during his time at the NFTS (which also include 2002’s Procter).

“When I graduated, I realised that type of character-driven story, that more humanist approach, was what I wanted to do,” he says. “So the NFTS really played into that. It gave me good craft skills, the procedures to develop, shoot and edit. I still stick to some of the things I learned then for how I run my sets today.”

Looking back on Still 20 years later, he says, “In many ways it was a mess of a film but I’m very proud of it. You have to be generous with your early work as a filmmaker… If you look at what I was exploring with the themes of time and the sense of showing thinking in cinema – to get into someone’s head – those are still themes I’m exploring with my films today. It’s an honest attempt as a young artist aiming too high – but I was learning along the way.”

Animation shorts

Second Class Mail (1985)

Dir. Alison Snowden

A bittersweet blend of humour and pathos, Snowden’s Second Class Mail tells of an elderly woman who receives a very special parcel in the post: an inflatable male companion that is amusingly distant from our notions of a sex accessory.

“I liked the idea of her sending away for an inflatable man doll as a way of contrasting her innocent character,” recalls Snowden. “I wanted it to have a naive, clunky style for the most part. I was still learning the basics of animation, so I designed the storyboard to be within my ability. I found learning walk cycles hard but managed to cheat by covering some of them up behind moving umbrellas or an aerial shot. Necessity is the mother of invention.”

Oscar-nominated in 1986, the film allowed Snowden to collaborate with other NFTS students, including Nick Park and her now life-partner David Fine, with whom she has since worked on projects including Bob’s Birthday, which won an Oscar in 1995. “My animation skills have definitely improved since those early beginnings,” she says. “But I try not to be too critical as it reflected a moment in time. I really enjoyed my time in the NFTS animation department making the film.”

Badgered (2005)

Dir. Sharon Colman

In Colman’s charming traditional animation, a badger finds his peaceful hibernation disturbed by the installation of nuclear warheads near his underground home.

“Because the idea came from the darker side of human behaviour, using satire and quirky characters was successful in telling this story,” says the filmmaker. “I had no idea whether it was going to work or not.”

Work it did, with Badgered nominated for an Oscar in 2006 and bringing Colman to the attention of DreamWorks Animation, where she worked in the story department, earning credits on How To Train Your Dragon and The Croods. She has gone on to work for other Hollywood studios (including on Warner Bros’ 2014 The Lego Movie) and is now making her own independent short.

“I love Badgered for many reasons,” says Colman. “It wasn’t until I came to the NFTS that I was able to combine my illustration background with a style that seemed to work.

“[For me], the animation has to work around the design, and sometimes things don’t move as planned. The badger’s front legs were too small to support his body when he lay down, so his large nose hit the ground first. Instead of fighting it, I let the design dictate how he was going to move. Sometimes unplanned humour is the best.”

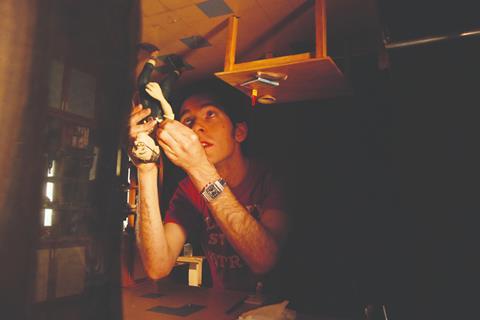

Head Over Heels (2012)

Dir. Tim Reckart

“The idea began as a single image – a house where someone lived on the floor and someone else lived on the ceiling,” explains Head Over Heels director Reckart. “This brought me to the idea of a married couple who have grown apart.”

The dialogue-free film tells the story of a couple living in the same house but on parallel tracks: her above, him below.

“Stop-motion was the perfect medium, because I wanted it to feel tangible,” says Reckart. “There’s a lot of symbolism, but I wanted the audience to invest in the reality of the world. Stop-motion brings that tactile reality to the screen.”

Head Over Heels premiered in Cannes Cinéfondation and was Oscar-nominated in 2013. It also landed Reckart his first studio directing job on Sony Animation’s The Star (2017). He credits the NFTS for preparing him to make that jump.

“We had room to explore and be creative, but the faculty didn’t shy away from making demands on us to elevate our craft,” he says. “Immediately after the film’s release, I was tortured by little regrets, moments where I wish I had animated something differently. Over the years I’ve forgotten all those little things and can admire what we were able to do with very limited resources.”

A Grand Day Out (1989)

Dir. Nick Park

A Grand Day Out might be the most well-known student film in history, introducing the now-legendary characters of Wallace and Gromit. Park’s 24-minute graduation film took him a total of seven years to make.

Luckily the school let him continue to use the facilities after his three-year course was over, and Aardman Animations hired him part-time and supported him to finish the film, which was made for only $16,500 (£12,000).

Park was the first pupil to use the NFTS stop-motion studio. He and fellow student Joan Ashworth had to persuade the school to buy its first 35mm stop-motion camera after some disastrous early rushes using a 16mm.

The simple story – told in Park’s now trademark stop-motion style – follows Wallace and his faithful dog Gromit, who build a rocket to go to the moon to see if it’s really made of cheese. For years Park had drawn early versions of his man and dog in sketchbooks, but it was during a student placement on Jim Henson and Frank Oz feature The Dark Crystal that he had the idea for Wallace to build a rocket in his basement.

Park recalls that making the short seemed tortuously slow – it took 18 months just to film the sequence of Wallace building the rocket. As he entered a sixth year of production, he decided to simplify the script just so he could definitely finish it.

Park describes his NFTS days as “fertile ground… I already had the animation bug in me” – he had previously studied at Sheffield Polytechnic – “but the school was such a playground to develop the craft of storytelling. The critiques from tutors and other students were really helpful.”

The school helped him draft a letter for actor Peter Sallis’ agent, offering him £50 to do the voice of Wallace (he said yes, and drove himself down to Beaconsfield for the recording).

A Grand Day Out was acquired by Channel 4 and won a Bafta but was beaten in the Oscar race by Park’s Creature Comforts. “I had worked on A Grand Day Out for seven years, then made Creature Comforts in three months at Aardman, so I pipped myself to the post,” he laughs.

Looking at A Grand Day Out now, Park can sometimes “cringe with embarrassment because the characters look a bit cruder… it’s like seeing early Mickey Mouse. But part of me is really flattered and honoured that it’s a student film that’s still known today and still playing. Its attraction in a way is its innocence and naivety. Some of the other Wallace & Gromit films start to get a bit darker and subtler.”

A Love Story (2016)

Dir. Anushka Naanayakkara

In A Love Story, a pair of woollen stop-motion heads experience a dialogue-free rollercoaster romance, from infatuation to heartbreak.

“We wanted to see how far we could stretch the limitations of language just using texture as a medium,” says Naanayakkara, who credits production designer Solrun Osk Jonsdottir and lead cinematographer Yinka Edward as her key creative collaborators in developing the look and feel of the film. “Eventually we decided a multiplane set-up was the best technique to give the wool the freedom it needed to convey the emotions of the characters.”

While Naanayakkara describes working on her complex animation as like “walking in a dark tunnel for a long time”, she is grateful to the NFTS, which “supported the team to make the best film we could”. It received numerous awards including a Bafta in 2017. “I was once asked at a Q&A, if I had unlimited money and time, would I continue to work on A Love Story, and the answer would be no,” she says. “That’s not to say it’s perfect, but wanting to improve it might take away some of what makes it connect with people.”

The 10 best fiction and animation shorts were selected by Screen International from a shortlist of 30 NFTS student films, including all Oscar nominees, a selection of Bafta nominees, and other acclaimed and award-winning titles.

![The Brightest SunScreen[Courtesy HKIFF]](https://d1nslcd7m2225b.cloudfront.net/Pictures/274x183/3/5/0/1448350_thebrightestsunscreencourtesyhkiff_312678.jpg)

No comments yet