Anatomy Of A Fall puts a family under the courtroom microscope after a woman is accused of murdering her husband. Director Justine Triet takes the stand to tell Screen about the creation of four crucial sequences.

It was the unwitnessed window plunge that was seen and heard around the world. In the early moments of Justine Triet’s Anatomy Of A Fall — co-written with her real-life partner Arthur Harari — a young boy and his dog return home to their chalet in the French Alps only to find the bloody body of his father lying immobile in the snow. Did he jump — or was he pushed by his wife? Giant billboards in Hollywood featuring the film’s star Sandra Hüller ask, “Did she kill her husband?” — but the answer is not found in the film’s 150-minute running time, and nor is it the point of the story.

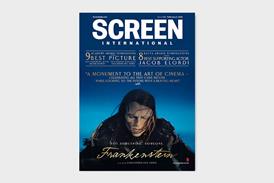

Anatomy Of A Fall is less about the titular fall and more about the anatomy of the couple and their son at the centre of the tragedy. The genre-defying film, which blends courtroom procedural with couples therapy, family drama and thriller elements, has caught the international spotlight since it first premiered at Cannes in May 2023. There it earned Triet a Palme d’Or, which has been followed by seven Bafta and five Academy Award nominations, including for best director, original screenplay and lead actress across both academies. It has also been a box-office hit with nearly 1.4 million tickets sold in France, and grossing $24m globally at press time. Spoilers ahead.

Sandra cuts short an interview

The scene: German writer Sandra Voyter (Sandra Hüller) drinks wine while being interviewed by a journalist (Camille Rutherford) at her cosy chalet in the French Alps. Sandra’s unseen husband starts blasting an instrumental cover of 50 Cent’s ‘P.I.M.P.’ from upstairs, forcing Sandra to cut the interview short.

Justine Triet: “This scene was the most complicated to film from a technical perspective. It’s also the only scene we had to shoot twice because it didn’t work the first time around. Our sound engineer blasted the music very loudly, then turned it off after a few seconds. I’d say ‘Action!’, the music would blare, the actors would start talking over it, then the music would shut off, just so the actors could reach the right pitch in their voices as if they were talking over the music, but we had to cut the sound so we could add it later in editing.

“We also had to co-ordinate all of the different elements in the same scene that we didn’t necessarily shoot on the same day — the child upstairs on the first floor, Sandra and the journalist downstairs — so we had to imagine everything. We also had to find the right balance in terms of how much Sandra was drinking and her level of seduction.

“It is impossible for the audience to know what is happening when the film begins. We will understand who this woman is and what her life is like later on, but in this moment, it all needed to be mysterious. This scene was so complicated because it’s so weird. We don’t really know who these people are yet, which is the point. It’s a very strange scene in so many ways.

“It’s a movie about perception and distance and reality. The audience is never at an appropriate distance from the characters — we’re either too close or too far away. The whole film is a balance between being close — almost too close — to this couple, dissecting their relationship, and then cutting to people who are far removed from the situation in the courtroom trying to analyse it. The film is a constant back and forth between both poles. This first scene is a real macro vision of the family and the couple. It’s also completely incomprehensible. We’ll spend the next two-and-a-half hours trying to explain what we see in this opening scene.

“‘P.I.M.P.’ wasn’t our first choice for the song. It was meant to be Dolly Parton’s ‘Jolene’, but her team wouldn’t give us the rights. We’d even written specific dialogue for the later courtroom scenes that analysed the lyrics of that song, like ‘please don’t take my man’, that we had to get rid of. I’d had this lyric-free version of ‘P.I.M.P.’ on my computer. It’s so displaced in terms of what’s happening in the scene itself. It’s very playful. It’s a bit anti-Kubrick — he’d be blasting Mozart or a piece of classical music. Historically, in genre films, there is a gap between the music and for example, a moment of violence or horror.

“The lyrics of the original song are actually quite misogynistic. I’m very obsessional — when I love a song, I play it on repeat for months. ‘P.I.M.P.’ has yet to irritate me, which is crazy because I’ve listened to it more than any ears should listen to one song.”

Sandra prepares her trial answers

The scene: Sandra prepares for her trial with her lawyer (Swann Arlaud), who is filming her with a video camera. She talks about her husband Samuel, and how things changed between them when their son Daniel had an accident that left him partially visually impaired.

Triet: “This is one of the scenes I like the most. It’s one of the first scenes with Sandra where she’s really exposing herself, where she is expressing herself and actually speaking. In fact, we don’t really get to know her for the first 50 minutes or so of the film. She’s someone very abstract, she says very little, then we see her in this scene reciting what is almost a monologue that lasts for several minutes. She talks about how she first met Samuel, which is a scene that is very important to the film in that we ‘meet’ these two people we will end up needing to judge later on. As a spectator, we judge them even before they enter the courtroom.

“This scene is the moment the audience understands that it will be hard to judge this woman because she is a writer, she has mastered the art of telling a story. She has to be able to say, ‘This is my story and you have to believe me.’ She also needs to do it in English, which isn’t her native language. We can see here that she is able to manipulate telling her life story to her own advantage, but at the same time, we can see she is very emotional.

“At the end of this scene she — and we as an audience — understand that the situation is truly horrible, that what is coming will be a nightmare. Sandra asks her lawyer not to tarnish the image of the man she once loved and he says he will try, but they — and we — know the case will be very violent.

“This scene is extremely complex. That’s why I love it so much. We learn who this woman is, yet we don’t really know her. When she starts to talk about her son’s accident, we wonder if she actually is so perverse she is capable of faking tears to show how her son’s visual impairment has affected her just to win the case, or if she is truly experiencing such emotion.

“In my fantasy, what I imagined of Sandra [Hüller] wasn’t what she did. She proposed something much less cliché, more modern — she acted as if it were a documentary. I told her to act as if she was innocent — she played it raw. Audiences identify with her because she’s not perfect, but she’s real. She’s not a heroine, she is not a perfect victim, but as a spectator, I find perfect victims and angelic women boring to watch on screen.”

Sandra and Samuel’s fight is revealed

The scene: The courtroom is listening to an audio recording of a blowout fight between Sandra and her husband (Samuel Theis) the day before he died — a flashback scene shown to the audience, but only heard in court.

Triet: “This scene is the most precisely written of everything we shot. We wrote at least 30 different versions of this scene alone. It was written, then rewritten, then rewritten, then translated into English, then I didn’t like the English translation, then we added the French subtitles and then realised things didn’t work, so we rewrote again. I was obsessed with every word.

“The translation was often less original in English, so sometimes it took longer to get the precise words right. We spent hours debating certain phrases. We spoke mostly English on set. Sandra often responded to me in French, but I asked everyone to speak in English. I did have to ask Sandra’s language coach for a list of more adjectives at one point so I could better describe what I was asking for.

“The scene lasts for 10 minutes — it’s very long. The end of the scene is quite violent in terms of the soundbites the courtroom hears. We had originally added several words like ‘drop dead’, but the actors changed a few things. In addition to the dialogue, we spent hours talking about the placement of the actors’ bodies. We decided to have them start off physically far away — he is at the counter and she is at the table eating spaghetti and, as the scene goes on, they move closer and closer to each other.

“We used two cameras to shoot it — which is rare for me, but the actors were in such a highly strung emotional state, we needed to have a lot of material to draw from. It took us two days to shoot this scene. It was the most complex from an emotional standpoint and very physically draining for the actors — they were exhausted.

“The biggest challenge was to make an extremely personal film about a family and a couple. Above all, to ask the question, what does it mean to live together in reciprocity? Is it possible for a couple to live together and for both to feel fulfilled? The film goes to a dark place, but the audience still connects to them. My biggest fear was, will audiences empathise with them? Are they an annoying intellectual couple or will people relate?”

Daniel delivers crucial testimony

The scene: Daniel (Milo Machado Graner) is testifying for the second time in the courtroom. He describes a conversation he had with his father that features a flashback scene in a car; we see his father speaking to him, but hear Daniel’s voice.

Triet: “This was among the most difficult days of filming. It’s when Milo’s character is meant to undergo a change in perspective as he returns to testify. We filmed this scene all day. We did 70 different takes. After around 45 of them, I could tell Milo was uncomfortable. I started to panic — I said, ‘This isn’t working.’

For Milo’s sake, I tried to hide my disappointment even though the scene wasn’t what I’d imagined. The crew was looking at me like, ‘What are we going to do?’ I was having trouble explaining to Milo what I was looking for.

“Finally, something clicked. After hours and hours of filming — don’t worry, he took breaks, he ate, we didn’t torture him! — he came back on set and he just got it. In that moment, I saw a maturity come over him. Milo has a curiosity that is rare for any actor, let alone a child actor. There’s something about him that’s different than other kids — he’s obsessive and always looking for another way to do something, to do it better.

“It was important to me that the courtroom scenes were realistic, and unlike most legal procedurals we see in the US that border on cliché. When I was in my mid-20s, I spent a lot of time in courtrooms, I was making documentaries so I was close to this world and watched cases unfold in real time. What we’re used to seeing in fictional courtrooms is much different than the reality, so I wanted to show something messier, not as symmetrical, much more like the way the justice system works in France which is more free, borderline-anarchic.

“The actors also brought something more modern. Antoine Reinartz, who plays the prosecutor, doesn’t look like an old-school French lawyer with a deep voice. He is aggressive but does it with a smile. Swann [Arlaud], Sandra’s lawyer, is also modern — he’s not like a hunky 1970s hero, he’s more feminine, more androgynous.

“This is a key scene. The film is as much about this woman on trial as it is about her boy who will have to learn to live with doubt for the rest of his life. I’ve never experienced precisely what Daniel endures, but often in life I’ve needed to form an opinion. Growing up is accepting what we don’t know to be certain and moving forward anyway.”

No comments yet