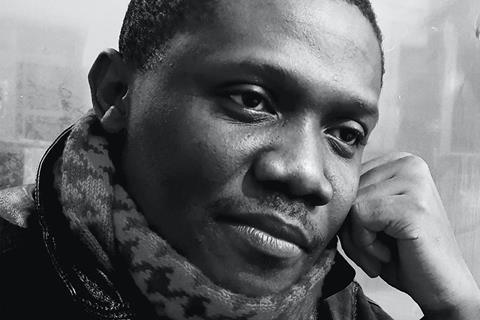

Nigerian filmmaker CJ ‘Fiery’ Obasi says it’s a “dream” for his third feature Mami Wata to premiere at Sundance – which is fitting because the idea for the film came to him in a dream-like vision in 2016.

Using West African folklore as his jumping off point, Obasi’s original story looks at villagers in a fictional West African village who worship the titular mermaid-like deity; but when the male villagers plant doubt about Mami Wata and her female intermediaries, chaos breaks out in the village.

The film premiered on Jan 23 in Sundance’s World Cinema Dramatic Competition and CAA handles North American rights. The project has taken part in Ouagu Film Lab, Less Is More, Durban FilmMart, EAVE, Venice Production Bridge, and FESPACO’s Les Ateliers Yennenga (backed by the Red Sea Film Fund). Mami Wata’s partners include the director’s own company Fiery Film, Nigeria’s Palmwine Media, Swiss Fund Visions Sud Est and France’s iFind.

Obasi’s past features are the zombie thriller Ojuju (which played at Fantasia) and crime story O-Town (which played in Goteborg). He is also part of Surreal16 collective which has made omnibus films like Juju Stories (a prizewinner at Locarno).

Mami Wata marks Sundance’s first feature selected by a Nigerian filmmaker with Nigerian funding. After Sundance, Mami Wata will screen in the Fiction Feature Competition at FESPACO.

What sparked this idea back in 2016 to make a film inspired by the goddess Mami Wata?

I had a vision. I literally fell into a trance-like state, which has happened to me no more than four times in my entire life. As a child, I had a very vivid imagination and I could see imaginary visuals. In 2016, I had this vision of a beach where I saw this young woman walking towards the ocean and she walked right past me and heads towards the goddess. I can still see it clearly now, I get goosebumps when I talk about it because it’s so clear. And the vision was in black and white. So I knew what my next movie had to be. And that’s the scene at the end of the film.

How did you take that initial vision and turn it into this richer story that looks at themes like matriarchy vs patriarchy and the price of progress?

That was a six-year journey to figure that out. At first, because of my past work, I was thinking the film would become a revenge thriller. Everyone who read the drafts loved it, but deep within me I knew it wasn’t what was in my heart, and the feeling from that vision. So after writing 9 drafts I started again in 2018 and went to several labs with it. I needed an internal dialogue with myself about why I wanted to make this film and what I could tell that was uniquely me. So now the characters of Prisca and Zinwe are drawn from my late sisters. And after I had cracked that code, the rest came together in an almost magical way.

It’s a very feminist story, and you mentioned your late sisters, are they one reason you were comfortable telling such a female-driven story?

I wanted to see people who look like my sisters and the women who raised me represented visually. We don’t usually see African women represented like this.

Why did you shoot in the Benin Republic instead of in Nigeria where you shot your last two features?

It was about finding the right locations. We did a recce in Nigeria back in 2016 and all those fishing villages looked more modernised than we had in mind. In 2020 we got the idea of Benin, it’s literally next door to Nigeria and the beaches are lovely. It looked like the vision I had. There is a special vibe and energy in Benin and the villages and nature have an untouched beauty. But it’s not a backward beauty – I wanted to make a rural village African story without the usual way of these places looking impoverished in films. The camera’s gaze usually looks down on them and we wanted to look up to them. We wanted our cast to look like gods were in the camera.

You mentioned wanting to shoot people like they are gods. What else can you tell us about the visual language and especially the way you lit the film?

We found the DoP of my dreams, Lílis Soares [Brazilian cinematographer whose credits include A Day With Jerusa]. I wanted someone who could capture what was in my head but was also on their own personal journey of development.

We watched a few black and white films just to know what we didn’t want to do. Then we watched films that were innovative in their narratives, because we wanted to break a few rules. We called ourselves to order every time we did a shot because we were filming African people and we didn’t want that typical sympathetic gaze, like we are supposed to feel sorry for these people. I wanted an empathetic gaze, where you connect with someone. That was the human side of the cinematography.

And we wanted to light them in a way that reinvented the code, that you could be regular African folk and not have to be a superhero to look amazing.

I know you’re a film obsessive, did you have many other film references in your head?

One might be Kurosawa, the way he framed his shots is not just about the character, it’s about everything happening within that shot. In a Kurosawa shot, you can see someone sitting in a field. There is wind blowing on the grass, there is a tree in the distance and a bird in the horizon. You’re taking the entire image, and very few big few filmmakers can do this.

Your wife Oge Obasi is your producer, how do you manage that partnership?

It got us to Sundance, so it must be working (laughs). We both understand our roles, I don’t produce because she’s better at producing, and she doesn’t direct. We have a deep respect for each other’s craft.

Does it feel like the world is waking up to Nigeria’s independent film scene?

People are waking up very slowly. People used to have a certain image of what a Nigerian filmmaker would be. And then they realise I am doing something different. There was an initial kickback but now people have accepted I’m on a different path.

How did it feel to get into Sundance?

I wrote on a vision board back in 2018 that this film would premiere in Sundance. I’d been watching clips of all these filmmakers at Sundance like Kevin Smith and Tarantino in the snow. So, it’s a dream to be here.

![The Brightest SunScreen[Courtesy HKIFF]](https://d1nslcd7m2225b.cloudfront.net/Pictures/274x183/3/5/0/1448350_thebrightestsunscreencourtesyhkiff_312678.jpg)

No comments yet