Director Jonathan Hacker worked closely with Saudi authorities to access found footage for his documentary Path Of Blood, about young Al-Qaeda recruits.

It is a rain-sodden November evening in London’s Westminster and there are long queues to get past security into the UK parliamentary building of Portcullis House. It is two weeks before a crucial parliamentary vote on the UK’s membership of the European Union. Mingling with the throngs of pro and anti-EU lobbyists are, however, a handful of Bafta members and counter-terrorism experts.

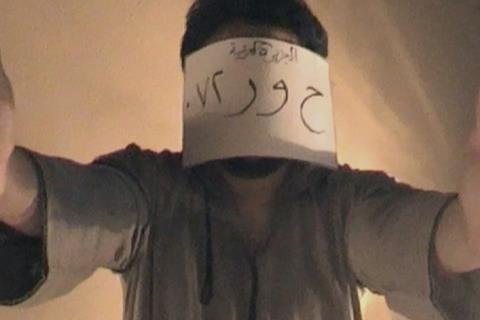

They are in attendance for a screening of UK director Jonathan Hacker’s documentary Path Of Blood. The film reconstructs from some 500 hours of home video-style camera footage the final days of young Al Qaeda recruits involved in a string of deadly attacks across Saudi Arabia between 2003 and 2009.

The event is being hosted by Neil Coyle, member of Parliament for Bermondsey and Old Southwark, whose constituency was the scene of the deadly London Bridge and Borough Market terror attack in the summer of 2017.

Coyle believes the film — which was released theatrically in the UK over the summer by Trinity Film and comes out on DVD this month — offers important lessons around the radicalisation of youngsters.

Insightful and disturbing, the documentary reveals the human side of the young Al Qaeda footsoldiers. Scenes showing them relaxing over non-alcoholic beers, playing football or goofing about in face-to-face interviews are at odds with the horrific acts they went on to commit. “We wanted to take a more nuanced look at terrorism,” explains the filmmaker to the audience in a lively Q&A after the screening.

Hacker first heard about the existence of the Al Qaeda “home movie” footage from Saudi journalists Abdulrahman Al Rashed and Adel Al Abdulkarim in 2011. “I’d done a film previously on suicide bombers for the BBC, Britain’s First Suicide Bomber, and they approached me to see if I was interested in the project,” explains the filmmaker. Al Rashed and Al Abdulkarim take executive producer credits on the film alongside The Hurt Locker and Zero Dark Thirty writer and producer Mark Boal, who was drawn to the project for the “startling and absolutely unique” raw footage. Hacker also produces through his London-based OR Media.

The filmmaker flew out to meet Saudi Arabia’s then security tsar, Prince Muhammad Bin Nayef, in late 2011. He had masterminded the country’s counter-terrorism activities at the height of the Al Qaeda campaign and had the ultimate say on the use of the found footage.

Arriving late for his meeting after his plane was stuck on the tarmac in London due to snowy conditions, Hacker was whisked through airport security and into a waiting car bound for a secret military base in the desert. “It was night-time and because it was a secret base the driver couldn’t find it. We ended up being given a police escort with me changing into my suit in the back seat,” recounts Hacker.

The prince put the filmmaker at ease with tales of smoking by the bins with former MI5 chief Eliza Manningham-Buller when Bin Nayef had trained in counter-terrorism with the British secret service in London in the 1990s, before agreeing to allow access to tapes that had been retrieved during raids at various Al Qaeda safe houses.

“They were still in the suitcases in which they had been found. There were literally piles of tapes. Nothing had been logged,” says Hacker.

Expert insight

Hacker drafted in Middle East expert and Arabic speaker Thomas Small to do a first assessment of the material. It was no easy feat. The sound and image quality was poor, while the dialects and slang of the jihadists made the dialogue nearly incomprehensible, even to his trained ear.

“I was overwhelmed initially by the sheer amount of footage, the vast majority of which was not usable,” says Small, who went on to co-write an accompanying eponymous book with Hacker, and also serves as co-producer on the film. “I was focused on how terrible the footage was but it was Jonathan, as an experienced filmmaker, who knew that the gems he could see would make a film.”

In an unprecedented move, Saudi security forces also supplied footage they had shot over the period and agreed to give in-depth briefings about their war on the Al Qaeda cells, which, Hacker says, had barely been reported at the time.

“We realised we could tell a story cross-cutting these two elements,” he explains. “I saw a way I could shape the film as cat-and-mouse thriller. While there are no single protagonists in the film, the forces of Al Qaeda and the forces of the security services become collective characters in a way.”

The resulting film is a fast-paced work giving insight into the battle between extremist groups, Saudi state security forces and in the Muslim world at large. Hacker hopes that, on a more universal level, the film also debunks some of the myths around extremist groups.

“Most people, when they think of terrorists, have a two-dimensional, shadowy sense of who these people are. They either think of them as James Bond villains or fanatics, but it’s important to understand that the people who join terrorist organisations are ordinary people.”

![The Brightest SunScreen[Courtesy HKIFF]](https://d1nslcd7m2225b.cloudfront.net/Pictures/274x183/3/5/0/1448350_thebrightestsunscreencourtesyhkiff_312678.jpg)

No comments yet