TÁR writer/director Todd Field first met Cate Blanchett a decade ago while working on an unrealised project with Joan Didion.

“I had a tremendous meeting with her,” recalls the filmmaker, Oscar-nominated for his previous features, Little Children and In The Bedroom. “I was sitting across from one of the great minds I had ever broken bread with. Her capacity to examine narrative in a multifaceted, holistic manner, outside the obvious concerns anyone would have as a performer, was so tremendous, and that conversation so rich, I wanted to be in dialogue with her at some point.”

So when Field sat down to write the story of Lydia Tár, a world-class conductor with the Berlin Philharmonic and a monstrous narcissist, whose formidable professional reputation crumbles when past indiscretions rear their ugly heads, Blanchett appeared to him. “I thought, ‘Oh, that’s interesting,’ and brushed it aside. But she kept turning up every morning and I thought, ‘This is unignorable, clearly, I’m writing this character for Cate.’”

Fortunately, Blanchett agreed to the role, her powerful performance already winning her a Golden Globe, a Critics Choice award, and Oscar, Bafta and Screen Actors Guild nominations. Field, too, has been roundly nominated for his work as both writer and director. Here he talks through four scenes from TÁR, each revealing a different side to Blanchett’s layered performance. There are spoilers ahead.

Lydia Tár gives a Juilliard masterclass

The scene: Lydia gives a guest masterclass at Juilliard. But when Max (Zethphan Smith-Gneist), a young music student, presumes to dismiss Bach on ideological grounds, Lydia takes him brutally to task, in a 10-minute unbroken take.

Todd FIELD: “This follows two other very long scenes, but we’ve still not really said hello to her. We’ve seen the different facets of how she handles herself in very particular professional situations, and now she’s been tasked to do her friend a favour and do this masterclass.

“She’s already had a very long day. She’s a bit on her heels. The scene begins with a young student playing a piece of music by Anna Thorvaldsdottir. And Lydia starts to take a line of inquiry with this student as to what their intent was in choosing this piece, because she feels as if the music has no intent.

“And for this character at this point in her life, everything is about intention. She’s looking at legacy. Her whole life is built around canonical work. That’s where her inquiry begins, about separating the art from the artist, centred around the student’s reaction to her suggestion that maybe he should be playing Bach instead. That’s where the fuse is lit.

“It’s an impossible shot. There’s no Steadicam, no crane, no wires. The only way to make that shot was to build our own equipment, so you would have absolutely rock solid, crane-like compositions, 36 [camera moves] in all, an uninterrupted take and hopefully not have people say, ‘Wow, how impressive,’ [and, instead] they’re involved in her performance. Keep in mind, it’s the first time we’ve seen her stand, other than backstage, it’s the first time we’ve seen her move, so it was important she had control over the time.

“It was done through a combination of grip equipment and a remote head, and four large men in stocking feet, and one camera operator in a tiny hallway with [DoP] Florian Hoffmeister and myself hunched over his shoulder, holding our breath, and days and days of blocking rehearsals with Cate and a full crew and those students to figure out where we needed to be and when.

“It was a very careful pas de deux between those four grips, camera operator Danny Bishop, and Cate. It was quite something. We allowed two days for it. And the first take was absolutely perfect, except for the very end when the student walks up the stairs past her and she walks down and there was a stumble and we missed it. We thought, ‘Okay, we’re going to get it on the next take.’ Well, we didn’t. We shot all that day, and all the next day. We only got it in the very last take. I believe we did it 12 times.”

Lydia finally conducts in the film

The scene: Lydia conducts the Berlin Philharmonic for the first time as it rehearses for a live recording of Mahler’s ‘Symphony Number Five’.

Field: “We know she’s a conductor. That’s all they’ve been talking about, but it’s a little bit like if you were doing an erotic film and you’re waiting for the big sex scene, you really don’t want to start the movie that way. There’s a level of anticipation — when are we going to see this horse come out of the gate? So that was the idea about this happening late.

“The way we meet her on the podium is very dramatic. That’s an 18mm [lens], Super 35, straight up her nostrils. That was an afterthought, and I’m so happy I did it because it was a great way to meet her. In terms of [real life] rehearsal footage, there’s not a great deal of it available, but it’s so intoxicating because it’s so messy. You’re stopping and starting, and you see the personality of these conductors, and the pointillistic way in which they compose a picture of a piece of music, and how that differs based on the tiniest things.

“So, that was important. It’s the first time we see how her gut works, how her ear works, because, like a lot of conductors, she’s attenuated to certain sounds, and the world bothers her because she can’t control those. This is the one place where it can be perfect for her.

“We shot all the rehearsals at the beginning. The very first day we had 95 camera set-ups with an orchestra used to rehearsing two-and-a-half hours and a break, and another two‑and-a-half hours and a break. When we told them we were going to need them for 10-hour days, they thought we were crazy. They said, ‘We already know this music.’ And we said, ‘No, you’re going to be acting.’ It’s going to be looks, and how you’re responding.

“Cate had never conducted an orchestra before and they had never acted in a film before, so it was a real challenge for us collectively, because it was supposed to happen at the very end of the shoot. Cate was supposed to have all this time to get ready and it didn’t work out that way. As daunting as it was, we felt like we climbed Everest. Then we had a 45-day shoot ahead of us.

“But for her to be able to stand up there and conduct an orchestra for real, she got to feel something very few human beings on Earth get to feel, which is what it’s like to have that sound and that power come through you, and command it. I think that informed her performance hugely because, after that, it was real for her.”

Lydia protects her daughter at school

The scene: Lydia returns to Berlin where her wife Sharon (Nina Hoss) says their adopted daughter Petra (Mila Bogojevic) might be being bullied at school. The next morning, Lydia asks Petra to point out the girl responsible, Johanna (Alma Löhr), and goes over to threaten her if she ever touches her daughter again.

Field: “A couple of scenes previously — when Lydia first arrives home and it’s the first time we meet her wife, the concertmaster Sharon Goodnow — they have this dance. During that dance, Sharon says, ‘I’m worried about Petra.’ She’s been coming home with bruises on her shins. There is bullying that goes on with a lot of Syrian immigrants, which is what their adopted child is.

“Cate and I had talked a lot about this, in terms of Lydia’s background, what was her childhood like? We were both convinced she had been heavily bullied as a child, and that had been part of who she is. Oftentimes, people who are bullied become bullies themselves, as a form of protection.

“So Sharon very innocently, or perhaps not so innocently, [tells Lydia about it]. She kind of knows she doesn’t have to say very much because Lydia is all about clearing the deck. So if she puts a problem in front of her, it’s not like Tár is going to show up to a PTA meeting — she’s going to take care of it. She’s going to take care of it fast, and she’s going to be very efficient about it. And Sharon’s hands are completely clean. That would go for familial life, or social life, or for orchestra life. She knows she’ll get it done and she does.

“That scene was an awful lot of fun to shoot because the children were marvellous. The child who played Johanna was incredible. She has a sister who’s also in that scene. It’s an important scene. This is the first time you see what [Lydia is] capable of. I’ve been in screenings where that gets laughter I wouldn’t expect.”

Lydia washes after helping her neighbour

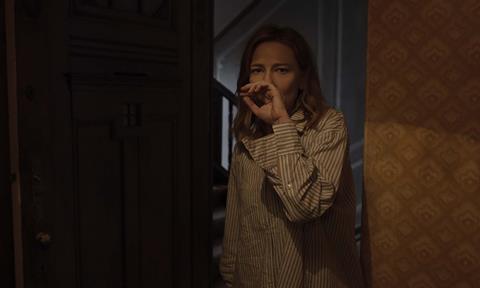

The scene: Struggling to compose in the old Berlin apartment where she lived when she met Sharon, and refuses to give up, Lydia is interrupted by neighbour Eleanor (Tilla Kratochwil) who badgers her into helping lift her invalid mother off the floor. Lydia relents but when she returns, she strips off and washes herself in the kitchen sink.

Field: “Eleanor is always bothering her, but she needs help and is desperate. She commands this character who commands everyone else that she has to come. There’s such primal force in this neighbour, that [Lydia] must obey. And she must help this woman who’s completely vulnerable. [The mother is] unclothed, covered in her own faeces, in a desperate situation, and she is compelled to help, despite herself.

“In the script, she was going to come back and jump in the shower. Cate said, ‘She’s a germophobe,’ so when she ran back in, she wanted to strip off everything that had touched that situation. Cate was adamant she wanted to do that. Going to the shower, it would have been another shower scene. Here, she’s so vulnerable; she’s throwing her nightgown into the garbage, not really thinking about it too much.

“Even the way she’s cleaning up is sort of unthinking, she’s at the kitchen sink, scrubbing herself down. It’s odd. That was something we came up with on the day. We had the idea and then we did it. Like many, many things in this film, there would be a plan in the morning and the two of us would have a conversation and things would change. We’d talk through a scene and might completely turn it on its head.

“That was a real testament to the crew, especially a German crew, because they like to plan, they’re very literal, they don’t like it when you change things. They’d say, ‘But it’s in the script.’ And I’d say, ‘Yeah, I wrote the script.’ [They would say] ‘We plan this. You have to do it like this.’ And I’d say, ‘No, I don’t.’

“Florian got used to it very quickly; he knew he was going to have to light 360 every single day because things were liable to change.”

No comments yet