“It’s like turning up at the scene of an accident, and no one’s really got their head around that they’re going to be in hospital for the next three weeks.” This is how one crew member describes the state of shock UK below-the-line workers have found themselves in following the onset of the SAG-AFTRA strike.

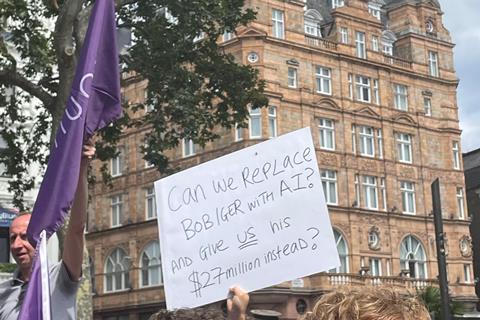

Less than a month into the SAG-AFTRA strike, which concerns members of the US actors’ union rallying against US studios and streamers on issues of insufficient payment and the threat to jobs of artificial intelligence (AI), the impact in the UK has been substantial. A high volume of US studio and streamer projects are filmed in the UK, thanks to solid tax incentives and highly-skilled crew. Major features to halt include Wicked, How To Train Your Dragon and Speak No Evil for Universal; Disney’s Deadpool 3 and Andor series; Warner Bros and Netflix series The Sandman; and AppleTV’s Silo.

There are some big projects still shooting in the UK – Paddington In Peru is ongoing without US actor Rachel Zegler; sources say Paramount’s Sonic The Hedgehog 3 is gearing up to shoot, not involving actors from September, using a splinter unit to capture plate shots; and Netflix also has some series in production. But there isn’t enough to go around.

UK creative industries union Bectu estimates “thousands” of crew have been put out of work in the UK following the strike commencement, and it’s not just the US productions shutting down that’s the issue.

“It’s a perfect storm” says Bectu’s national secretary of London production and regional production division, Spencer MacDonald. “All the areas have had a downturn. Unscripted, commercials. There’s not much scope for moving around at the moment.

“Even the people who were regularly working and really good at their job are fumbling around trying to get some work. When these people have to start doing that, you know things aren’t great.”

Several UK producers Screen has spoken to reference a dearth of UK independent production happening at the moment, with many facing funding challenges, or choosing to push production into next year for fear of complications around casting in light of the strikes.

For newer crew in the industry, there are even fewer places to go, as they must now compete with highly-experienced workers who are willing to take pay cuts and go into more junior roles on lower-budget features to keep money coming in. And those who are working are trying to keep their projects under-the-radar, with actors not keen on the optics of working in this period even if the projects are not struck in the eyes of SAG-AFTRA, and some crew feeling a sense of guilt as their peers grapple with unemployment.

A production manager told Screen that they’ve been inundated with CVs since the strike began, and even had someone physically turn up at their office looking for work. “I think what’s made it doubly difficult for crew is the start of the year was very slow, the renegotiation of the [Pact-Bectu] TV drama agreement at the end of last year caused a lot of production to postpone until that was in place. Then there was the pending writers’ strike [Writers’ Guild of America have been striking since May 2] so nothing started up.

“A lot of people burned through their savings. Then the jobs that did start back up again have now shut down. They were the lifeline. I’ve spoken to friends with two to four weeks’ worth of money left, and that’s it. It’s not that people don’t support the strikes, but we don’t necessarily see the benefit, and we’re bearing the brunt of the impact of it.”

“I’m borrowing left, right and centre,” reveals one hair and make-up designer.

For many, it’s meant flashbacks to the shutdown of Covid, but worse. “There’s nothing out there,” a special effects specialist tells Screen. “It’s like Covid, but without the support.”

“Even with Covid, the biggest thing to ever hit the economy globally, there was still a strategy, still a plan in place, in terms of how they were going to get people back to work,” agrees MacDonald. “It gave crew members a bit of reassurance that there was going to be resolution, and they were involved. But with this, it’s not their dispute, and they’re concerned about when will there be an end date.”

Most crew are self-employed, on freelance contracts, with one-week notice periods. Crews on halted projects have been put ‘on hiatus’ – there’s a promise of a job when production starts up again, but there’s no clarity if or when this might be, and they won’t be getting paid in the meantime.

MacDonald believes the US companies should be paying UK crew retainer fees. “We have started to contact some employers. If they want to retain their crew, are they going to pay a retainer? There doesn’t seem to be much of an appetite to talk about that.”

Screen contacted four of the biggest employers of UK crew, Warner Bros, Universal, Netflix and Disney, for comment on how they are addressing crew employment and the ‘hiatus’ process in this period. None had responded at time of publication.

“They pick the crew they want to use on a particular job. If they do go off and pick up alternative work, there are no guarantees they are going to be able to come back off it [if the strike ends],” says MacDonald.

“When it was busy and there was a mad gold rush for content, they [US companies] were paying [UK crew] retainers. They’ve done it before – it’s not completely alien.”

MacDonald notes that, in the past few months, Bectu’s membership has increased dramatically, as people seek support and advice. “It started more slowly when the writers’ strike was announced, but it wasn’t as pronounced. As soon as the SAG dispute happened, we saw a massive increase. The number of new joiners in the past month is at least double what we normally get.”

Similarly, the UK’s Film and TV Charity has also seen an increase in people applying for its stop-gap grants in recent weeks, that help those working in the film, TV and cinema sectors to meet urgent financial needs.

As of yet, no dedicated hardship fund has been set up to support below-the-line staff impacted by the strike in the UK. “It’s affecting smaller communities and businesses where we would normally be shooting on location,” says a location manager. “I would have expected a nod from the government to say we recognise this is a hidden industry and a hidden stream of money that impacts villages, cleaners, security, people who make coffee. There’s a lot going on there.”

One crew member Screen spoke to who is working on a US studio project with an uncertain future expressed concern about their colleagues’ mental health.

“A lot of people are clamming up. I’m avoiding the tea room – it’s devastating,” they say. “Before the strike people were saying they don’t know how they are going to manage. That was nothing to do with the strike, but people stretching themselves in good times. Then this has happened. It’s a bit of a shock.”

There’s a very real fear that the industry will hollow out. “It’s precarious work in the industry, it’s so insecure. If people have transferable skills, they’ll go elsewhere. We need to invest in people,” says MacDonald.

“Prevention is better than cure, but this industry tries to cure things rather than prevent. When production does return there will be a backlog, and if people have left, it’s going to magnify that problem. People in retrospect will look back and think – we could have done a bit more.”

“How the hell are we going to make money?”

It’s not just on-set production teams that are suffering. Screen has heard of camera rental houses, with hefty overheads owing to their storage facility costs, fearing they won’t be able to survive if the strikes go on beyond Christmas. And with press around struck projects also on hold, those who work with acting talent across the promotional circuit have also fallen on hard times.

Michael Miller is the founder of the Celebrity Stylist Union, which formed last year with the support of Bectu. Since the strike, stylists who work with actors doing press activities, such as junkets, premieres, interviews and photo shoots, have struggled.

“We’ve got no work. Absolutely nothing. It’s all been pulled until the strike is over. The release schedule is up in the air. We don’t know when we’re going to start again. A lot of us are trying to figure out how the hell we are going to make money.”

Miller notes, however, that a silver lining from the actors’ strike is it has opened up a conversation in the industry about problematic working conditions across the board. “In one way, it’s terrible we’ve lost all of our work,” he says. “But in another, it’s beginning to shine a light on the studios and streamers and show them for what they really are.

“The streamers have made the rates plummet. Netflix has a standardised $500 (£392) an outfit rate for stylists. We get paid per outfit, not for our time.” Miller says stylists aren’t compensated for hours spent sourcing the outfit, expenses, or the clothes, which means when all costs are factored in, many are working for under minimum wage.

Going forward

There’s cautious talk within the industry that the strikes will be over by early next year. Some are taking this time as a moment for existential reflection. “We’re so linked to the US,” a production manager posits. “Seeing how much the industry has shut down – is the UK industry really our own?”

With that comes a sense that the streamer and studio influence in the UK might wane. “I think the inflated [crew] rates we’ve seen over the past three or four years will be brought down,” they believe. “There will be fewer of the big shows, and big franchise films, and hopefully there will be more independent stuff. Streamers were cutting back anyway, and this period of strikes is giving companies time to restructure the way they are doing things. It does mean everyone is going to have to take a pay cut.”

“It’s the end of the golden age,” suggests one third assistant director. However, they don’t believe the US studios and streamers will retreat from shooting in the UK. “After the strike is done, more and more Americans I think are going to come here [to film], because we are cheaper and less protected. We should have a stronger union.”

For now, people are just keen to find work. “I’ve had a location manager saying he’ll do admin, sweep floors, anything just to work,” recalls the production manager. ”Everyone’s in a desparate situation.”

No comments yet