It is becoming a familiar scenario for smaller UK distributors. They have a new movie about to hit the screens but a very limited budget with which to market it. The film has bookings in 10 venues. Other cinemas want to show it. They know that if they accept these extra bookings, they will have to pay over £600 in additional certification charges. They therefore restrict the release.

The rub here is the fee tariff for the British Board of Film Classification (BBFC) which means as soon as a film goes out on more than 10 screens, the cost for certifying it doubles.

“I don’t for a minute want to suggest there shouldn’t be a BBFC but it can be very challenging,” says Pat Kelman, CEO of arthouse-focused distributor 606 Distribution, of the extra charge for expanding the theatrical footprint of films such as My Little Sister and Love According To Dalva. “The films that I am releasing are small generally but I have had opportunities to go wider and I’ve not been able to take them.”

Other smaller UK distributors echo Kelman’s view.

“Our view is that if [the BBFC] wanted to help independent films with relatively limited releases of up to 50 screens, they could have had a much more friendly system than this. This was a missed opportunity for them to help small releases,” says Christopher Hird, founder and managing director of Dartmouth Films, which had an indie documentary success last year with Eric Ravilious: Drawn To War.

Hird describes it as “absolutely bizarre” that the BBFC has introduced a system that “positively discriminates against the small and limited releases”.

“I fear the BBFC is stifling screen culture in the UK,” adds Zak Brilliant, head of sales and distribution at Met Film Group, while Jonny Tull of northeast England-based distribution and exhibition company Tull Stories says, “It just feels like a little bit of stress and strain that doesn’t need to be there.”

Robert Beeson of New Wave Films, which has been releasing arthouse films in the UK market since 2008 (upcoming titles include Albert Serra’s Pacifiction and Maryam Touzani’s The Blue Caftan), describes the BBFC’s approach as “a blunt instrument to decide what is a larger film and what isn’t a larger film”.

These distributors will often spend between 10% and 20% of their entire marketing budget on getting a film certified, with all pointing out that a 20-screen release for them is very different to 20 screens for a studio for whom the cost of certification is a tiny fraction of the overall P&A budget.

“With a small independent film, you’re lucky to get one show a day. Very often, particularly if you’re releasing documentaries, you might get three or four shows across a week,” Brilliant notes.

By contrast, big US studio movies will screen four times a day – or more.

“Extortionate charge”

Other distributors releasing films on a wider scale are also feeling the squeeze from BBFC charges. “It is an additional cost which is really eating into our budget,” says Jordan Pletts, campaign manager at Studio Soho Distribution, whose slate includes Joyland and Harka.

“We’ve experienced it more with films that we think can play in around 50 [screens]. If it goes over 50, you get slapped with this extortionate charge. What we find annoying is that if you’re doing a saturation release, you pay the same whether you’re in 51 or 400 screens. [These charges] only really sting the smaller distributors.”

“I find it difficult to have to think about the BBFC’s pricing structure to consider whether to take a series of one-off bookings that would put us over the WPR [widest point of release] threshold and incur possibly more costs than we would receive in incremental box office returns, especially if it’s after the release and into the film’s run,” says Eve Gabareau, founder and head of Modern Films. “I don’t think the BBFC should play any role in a commercial decision we make about booking a film but somehow they do.”

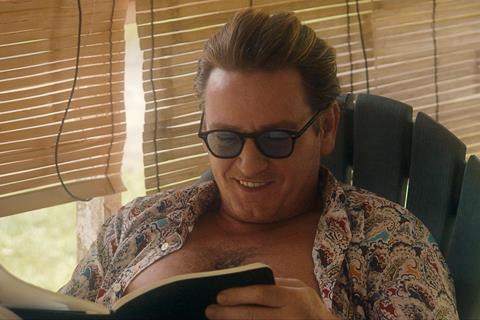

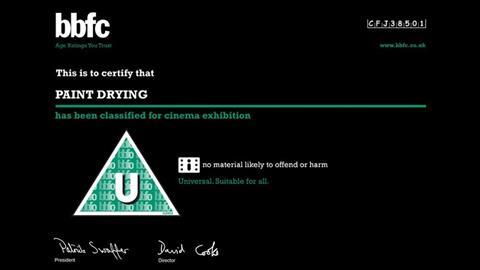

Ironically, the current tier system was introduced in response to earlier complaints about how films used to be classified. The BBFC had a standard rate per minute for everything. This one-size-fits-all approach meant Disney was paying the same amount for classification as the smallest independent distributor. When maverick filmmaker Charlie Shackleton submitted his 607-minute crowdfunded protest epic Paint Drying to the BBFC in 2016, the director received a U certificate – and a bill for £5,286.16.

In 2022, the BBFC finally introduced a two-tier classification fee tariff for theatrical submissions. This fee structure meant a lower tariff for smaller releases. The cut-off point was 20 screens: as long as indie distributors didn’t cross that number, they paid significantly less for certification.

This was welcomed although smaller distributors holding “one-day special” screenings were still being hit with hefty bills. (The BBFC has given ground on this issue.)

The cause of the smaller distributors’ disquiet now is the BBFC decision at the start of this year to add a third tier to its fee classification structure. Now, theatrical features released on up to 10 screens cost £575 to certify. For films on 11 to 50 screens, it is £1,200 and for 51 or more, it’s £1,780. All plus VAT of 20%.

This tweak was, as a BBFC spokesperson puts it, “to better reflect the range of different sizes of cinema film release”. The net result, however, has been to put the smaller distributors in a situation in which it makes more economic sense to limit the release of new movies.

Certificates and platforms

Criticism of the BBFC has been going on for almost as long as the organisation has been in existence. Founded as the British Board of Film Censors in 1912, it’s a self-funded, not-for-profit organisation created by the film industry itself in order to standardise ratings.

Early on, the BBFC issued only two classes of certificate, one applying to “universal” exhibition and the other to films not regarded as suitable for children. That has expanded over the years to the current system of seven ratings – U, PG, 12, 12A, 15, 18 and R18 – and in 2023, it deals with theatrical features, trailers, DVDs/Blu-Rays and VoD, with extra charges for each.

Netflix, Prime Video, Apple TV+, Curzon Home Cinema, Lionsgate+, Rakuten TV, Sky Store and YouTube Movies all now use the BBFC’s age ratings and content advice on their platforms.

Netflix has been granted the authority to do its own ratings in-house based on BBFC guidelines – and the BBFC audits some of its content each month to make sure accuracy and consistency are maintained.

“While there’s no legislation requiring services to carry BBFC ratings, our partners choose to work with us to do the right thing by families across the UK,” says BBFC chief executive David Austin. “Research has consistently shown that UK families recognise and value BBFC guidance and want there to be consistency across cinema, home video and online ratings.”

The BBFC declined to reveal how much Netflix is paying to self-certify its straight-to-platform titles but pointed out that any titles Netflix releases into UK cinemas will be classified by the BBFC and charged at the same rate as other theatrical distributors.

Many had hoped the BBFC would use the income from its deals with Netflix, Amazon and others to reduce the fees to smaller players, in effect helping to subsidise the release of independent and arthouse films in the UK market. Some distributors are also asking why, if Netflix is allowed to self-certify its titles, they can’t do the same.

It’s clear that some envy has built up toward the organisation.

“The BBFC has got quite a big pot of money in their reserve,” notes one. “They’re sitting in a building in Soho Square [in central London] that is massively undervalued. It was last valued about 15 years ago… and there are questions about their financing and giving back to the industry. They should be passing on some greater benefit to the sector.”

According to its 2021 annual report, in spite of operating losses the BBFC had capital and reserves of £12.6m, putting it in a far more robust financial position than other film trade organisations.

“I completely understand the concerns of smaller distributors, which is why we have always been extremely conscious of keeping our fees as low as possible,” says Austin. “Between 2007 and 2019, we brought our fees down by 33% in real terms, and since 2019 we have reduced the cost of classification for smaller releases by almost 50%.”

Austin points out a decade ago, when the BBFC sought to introduce a lower-fee tariff to support the release of smaller films, “the proposal was met with resistance from some distributors and so wasn’t implemented.” The sticking point then was that there would have been higher fees for films with a much wider release.

Paint Drying director Shackleton argues the “chasm” between smaller indie distributors and the major companies releasing blockbusters has now grown “so vast” that it would be fairer if the latter picked up most of the costs. Shackleton points out the majority of the films being released by the smaller indies are aimed at adult audiences, rather than families and children. In other words, the demographic much less impacted by ratings.

“Some of the frustration from smaller distributors comes from the fact that they’re having to get a certificate at all for films whose audience couldn’t care less what that certificate is,” he says.

For him, the key question is not about BBFC costs – which he regards as “reasonably fair for the work involved” – it’s about why some films need to be certified at all.

“My objection is always that this is pointless. I’m paying for this thing [a BBFC certificate] that I don’t want or need, getting these people to do all of this work that will have no material benefit to anyone,” Shackleton says.

He argues certification should be voluntary. “The studios are always going to want their big tentpole releases given these recognisable ratings that parents obviously care about. Then, me or a small distributor can choose whether they think there is any value in finding out that their seven-hour Lav Diaz film is a PG or whatever.”

What do exhibitors want?

What is inescapable, however, is that exhibitors and the local authorities in which their cinemas sit, want the reassurance brought by a certificate.

In theory, distributors could bypass the BBFC, approach local councils directly and get them to agree a film is fine to play. In practice, this rarely happens.

“Occasionally we have a festival screening and go to the council direct, but this can take time, depending on the council – not ideal,” says Clare Binns, managing director of exhibitor/distributor Picturehouse Cinemas and Picturehouse Entertainment. “We have to have a certification. If you don’t, you could end up with a customer who will find something not to their taste – offensive to them – and then you are just creating more problems.”

Says Austin of how the BBFC aims to be transparent about its decision-making: “We regularly seek input from experts in particular fields to inform our approach. We consult with child psychologists, education professionals, charities, and other organisations. We’re open and accountable – to the industry, local councils, government, parliament and to everyone in the UK, especially children and families.”

Giving back

The BBFC chief executive isn’t apologetic either about the organisation keeping its base in the heart of Soho, where property prices are at a premium, at a time when many other film companies have moved out of central London.

“We are using our building in the most effective way to bring down costs – savings that as a not-for-profit organisation we pass on to our customers,” Austin says. “Since Covid-19, we have reduced our footprint thanks to more remote working, and this has allowed us to rent out space, with the income generated used to subsidise our fees. We have also added new cinema facilities to 3 Soho Square to reduce our reliance upon expensive external screening rooms.”

The Soho Square location, Austin adds, “means that we can relatively easily visit our customers’ premises to view films, which they often ask us to do”.

Nor does Austin recognise the charge levelled at the BBFC that it isn’t “giving back” to the industry.

“We take our corporate social responsibility seriously and are proud to support the voluntary sector through charitable donations,” he insists. “Over recent years we have supported a number of vital campaigns and organisations, including the London Film School, MediCinema, the Homeless Film Festival and the National Film & Television School. Since 2001, we have donated over £1m, largely to film-related charitable causes.” (This works out to an average of £45,450 per year.)

Is it the BBFC’s responsibility to underwrite the business costs of smaller UK distributors? The distributors are not looking for handouts but facing a business reality.

“I often find that when the BBFC bill comes in, that can be the difference between me breaking even and making a loss,” says Kelman, who argues that a “threshold of 25 screens” would be a “more realistic” number for the lowest tier.

“You want the BBFC to be something you never really think about… but they’ve become such a disturbance. They kind of get in the way,” says another small distributor. “Their job is to certify, not to participate in the success of a film. Sometimes the BBFC gets more than the producers do.”

“I am doing it for love of cinema, not to turn a gigantic profit, and [to bring audiences] amazing films that wouldn’t get into cinemas otherwise,” says Tull of why he’d like to see the BBFC be more mindful of the role indie distributors play in the overall film ecosystem with its fee structures.

Whatever their gripes about fees, these distributors agree that the actual service provided by the BBFC is transparent, fast and fair. There are very few censorship rows of the sort that were commonplace in the era of Ken Russell’s The Devils and Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange.

Nonetheless, the distributors all have stories about not being able to take their films wider because the current tier system with its 10-screen break point is so heavily tilted against them. That means UK audiences are being denied the chance to see work which might otherwise have been available to them – a state of affairs surely to no-one’s advantage.

“We developed our current fee tariff in consultation with the Film Distributors’ Association and Government, with a third tier being added in direct response to industry feedback. We are open to reviewing the fee structure again in the future,” Austin says, raising the possibility that the distributors’ concerns can at least be looked at once more.

![The Brightest SunScreen[Courtesy HKIFF]](https://d1nslcd7m2225b.cloudfront.net/Pictures/274x183/3/5/0/1448350_thebrightestsunscreencourtesyhkiff_312678.jpg)

1 Readers' comment