The pay dispute at Picturehouse Cinemas hit the headlines when striking workers targeted last month’s BFI London Film Festival. Screen measures the impact on the wider UK exhibition sector.

A weekday evening midway through the BFI London Film Festival (LFF) and the protesters are out in force at Picturehouse Cinemas’ seven-screen flagship, Picturehouse Central, near London’s Piccadilly Circus, forming a picket line and chanting.

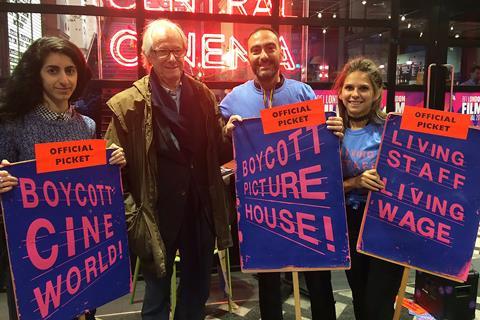

Alongside the protesting Picturehouse staff on this particular evening is double Palme d’Or-winning UK director Ken Loach. “It’s a very important dispute and is marked by the Picturehouse workers’ determination to get their due, which is a proper wage,” Loach tells Screen. “They [the picketers] are a wonderful, cheerful, brave group of people, mainly young, who risk their jobs to get proper pay. I have huge respect for them.”

The picket is good-natured. Loach, who is giving out leaflets on behalf of the strikers, says it is effective too. Some would-be cinemagoers turn away. Filmmaker Eugene Jarecki hears about the dispute and promptly cancels the Q&A for his Elvis Presley documentary Promised Land in support of the strike. One of the UK’s most famous screen celebrities, Benedict Cumberbatch, is photographed outside the cinema holding “Living Staff Living Wages” and “Boycott Picturehouse” leaflets.

The protests, which organisers billed as “the biggest cinema workers’ campaign in UK history”, were the continuation of a long-running dispute between management and staff over pay and conditions at Picturehouse. The standoff was embarrassing for the LFF and provoked awkward questions for the BFI.

For example, the protesters wanted to know why the BFI, which supported the Living Wage Foundation (the organisation setting an hourly wage based on the cost of living) and paid its own cinema staff at BFI Southbank the London Living Wage or above, was working so closely with an exhibitor that refused to honour the same principles. (The London Living Wage is £9.75 ($12.85) per hour at the time of writing but expected to rise by 30-40p in November. Nationally, the Real Living Wage is £8.45 per hour. The statutory National Living Wage for over-25s is currently £7.50.)

“They [the BFI] have known about our campaign since 2014,” says Nia Hughes, organising official at the BECTU sector of Prospect, the union representing the strikers (but which Picturehouse management refuses to recognise at many venues). “Their association with Picturehouse is bad for their reputation.”

In response, the BFI said this was an employment dispute in which “it had no involvement or jurisdiction”. “We pay the London Living Wage and we encourage others to do the same. We hoped the dispute was going to be resolved as quickly and amicably as possible,” a BFI spokesperson tells Screen.

The dispute has been running in one form or another since 2007, when workers at the Picturehouse-owned Ritzy Cinema in Brixton campaigned for increased wages and union recognition. It had become progressively more bitter, however, following the sale of Picturehouse to Cineworld in 2012 and the appointment of Moshe (Mooky) Greidinger as chief executive of Cineworld at the start of 2014.

Battle lines drawn

In advance of the LFF, Picturehouse had hired legal company Mishcon de Reya (a Living Wage employer itself), which fired off letters to BECTU warning any strike would be unlawful. Earlier this year, Picturehouse claimed it was subject to cyber attacks on its website and four employees were dismissed for gross misconduct as a result. (An unfair dismissal case is being pursued in an employment tribunal.)

Picturehouse management implied they were the ones being unfairly victimised. The company asserted that, once paid breaks are added in, its hourly wages of £9.30 in London and £8.36 elsewhere were equivalent to £9.92 and £8.92 over an eight-hour shift and that these had been agreed with its own in-house union, The Forum (described by protesters as a “sham union”). Its basic rates of hourly pay were also higher than at Cineworld or Odeon — and at many other independent venues in London. The company also described itself as “one of the highest-paying employers in the cinema industry”.

To some observers, the management’s refusal to come to an agreement with the protesters was baffling. If the cinema chain really was paying the equivalent of the Living Wage, as it claimed, why not then just pay the actual Living Wage? That would end the dispute.

Picturehouse and Cineworld management were not available for comment for this piece but earlier this summer Cineworld chairman Anthony Bloom told The Guardian that the board was “proud of our employment practices everywhere” but wary about becoming a Living Wage-accredited organisation. “If we agree to the Living Wage and it rises to £15 next year, we’ll be bound to follow that,” he commented. Contacted by Screen, the Living Wage Foundation indicated that there was no chance at all of the Living Wage rising to £15 next year. The London Living Wage was £9.15 in 2014, rose to £9.40 in 2015 and then to its present £9.75.

The protesters were quick to point out that Picturehouse’s parent company Cineworld was raking in sizeable profits — £93.8m in 2016 — and that Greidinger was on a huge remuneration package.

BECTU denies that Picturehouse was being picked on as a soft target, although it’s perhaps the case that the company’s communitarian brand values and liberal-tending customer base make this pay dispute a good one for BECTU to highlight. “They [Picturehouse] make huge amounts of profits out of being this ethical, independent, ‘bougie’ company,” says Hughes. “The BFI pay the Living Wage. Curzon pay the Living Wage. The Arthouse in Crouch End, which is a two-screen cinema right next to the five-screen Picturehouse, pays the Living Wage. Surely if a company of that size, which is tiny, can become a Living Wage-accredited employer, there’s no reason why Picturehouse and Cineworld can’t roll that out for all their employees across the country.”

Cineworld doesn’t pay the London Living Wage for new customer assistants or front-of-house staff. Neither do Odeon or Vue. “We don’t offer zero-hour contracts, and we pay more than the National Minimum Wage to all colleagues aged under 25,” an Odeon spokesperson tells Screen. “For colleagues aged over 25, we pay the National Living Wage. And for colleagues working in Central London (zone 1), we pay above the National Living Wage to all roles.”

As the dispute rumbled on, there were signs that the discontent was spreading. Picturehouse’s rival Curzon had made great store of being a Living Wage employer. However, when Curzon withdrew paid breaks in March 2017, some staff members cried foul. Curzon strongly defended its position. The company’s head of HR Emma Murphy points out that Curzon has paid the London Living Wage since the beginning of 2015. “We’ve increased our pay every year in line with the Living Wage, both in London and outside London,” she says. “It [the Living Wage] is something we committed to once we could afford to pay it. We agreed it was important, if we could afford it, to pay a fair wage.”

Read more: Ritzy staff dismissed in latest Picturehouse-Bectu flare-up

As for the vexed issue of unpaid breaks, Murphy says that is something which will be addressed in forthcoming negotiations with BECTU once the new rate of the Living Wage is announced.

Other exhibition chains make familiar arguments in defence of their wages policy. This is a low-margin business with very high utility costs. Part-time jobs in cinemas can be an attractive option for students or young film enthusiasts, they suggest; the zero-hour contracts under which many staff members are hired provide flexibility. Cinemas, they say, are exciting places to work — at least by comparison with pubs or fast-food restaurants. Most exhibitors, whether independent or multiplexes, offer free tickets and concessions on food and beverages to their staff members.

For the strikers, these arguments carry little weight. “We don’t want to be paid in popcorn” is a familiar sentiment.

For independent cinemas, total staff costs can be as high as 50% of income. They may be broadly sympathetic to the Picturehouse protesters but some point out that they can’t afford to pay the London Living Wage — and claim their staff members accept their situation. For example, at north London venue Rio Dalston (a registered charity), front-of-house staff receive £8.50 an hour. “This level is accepted in order that the cinema will be able to at least break even,” says programmer Peter Howden.

Worker solidarity

It is instructive to speak to a part-time employee at one of Odeon’s sites in the north of England. Speaking anonymously, she expresses her support for the Picturehouse protesters in London, even though she is paid considerably less than they are. (She is on £7.05 an hour, the minimum wage for people aged 21-24, with unpaid breaks.) The box offices at the venue have now been removed and replaced by ticket machines. This was supposed to increase efficiency but she says it has had the reverse effect. The machines are often broken and cinemagoers prefer to queue to buy their tickets from a person at the food counter.

“We pretty much do everything from the food stands because they barely give us enough hours to have someone to clean the screens,” the Odeon worker notes. “We used to have people greeting people when they came in but they don’t give us enough hours to do that now. We can’t check tickets either so we have quite a lot of people going in without tickets. We can’t check age rating properly because people buy tickets from the machine and go in without seeing anyone.”

For Loach, the importance of the Picturehouse dispute is that this is a test case. “This is why the employers are fighting so hard to resist it,” he suggests, noting that if Picturehouse management accept the Living Wage, other exhibitors will come under intense pressure to follow suit.

In the meantime, the strikes have shown the industry in a negative light at a time when UK film is worth £4.3bn to the economy and the BFI’s Future Film Skills action plan has only just been put in place to “open doors” into cinema for younger, more diverse workers. “For the industry, which wants and needs to continually engage with younger audiences, it [the negative publicity around Picturehouse] has to be a concern,” a BFI spokesperson comments. “Many partners across the film sector will be involved in the Future Film Skills action plan, and we will be encouraging all to pay the Living Wage.”

This feature first appeared in the November issue of Screen International. Click here to subscribe.

No comments yet