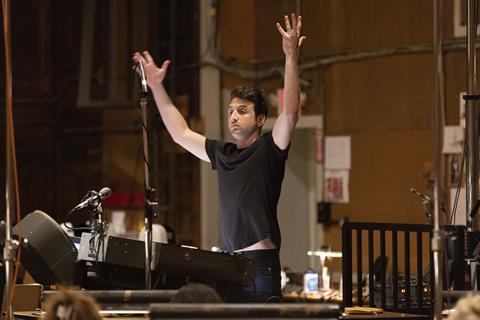

Justin Hurwitz works at a deliberate pace, and has stayed phenomenally loyal to filmmaker Damien Chazelle. The composer tells Valentina Valentini how his meticulous process translated into the wild, uninhibited soundtrack to Babylon.

While it is not unusual for filmmakers to establish regular working relationships with composers, it is rare for that partnership to remain exclusive on both sides. Which makes the creative connection between writer/director Damien Chazelle and composer Justin Hurwitz a real Hollywood rarity. The two — who first met as roommates at Harvard, where they made their first short film together — share a symbiotic drive and determination, and a working pace that may be called deliberate: Hurwitz worked on their fifth and most ambitious project to date, Babylon, for three years; on La La Land, it was four years.

“That’s not a normal amount of time,” says Hurwitz, referring to the usual timeframe and scope of a composer’s work on a film, which generally amounts to a few months during post-production. “But when [Damien] has got a movie, that’s all I want to do. I just want to kill myself for it and make it as good as my work can be.”

And while Hurwitz thinks that working with another director and on different types of projects could be a good thing, he is hesitant to do so. “I have such a special relationship with Damien,” he says. “The way he makes music part of his process from the very beginning to the very end, and given my obsessive and perfectionist personality, it gives me time to feel like I can do my best work. I have months to search for the themes while he is developing the script, months to write demos, months to write to picture, months to mix. Most filmmakers don’t think about music until much later, so I would be concerned about my own timeline — I’m a very slow writer and slow orchestrator.”

Considering Hurwitz’s accomplishments as a composer, and his La La Land Oscar wins for original score and original song (‘City Of Stars’, shared with lyricists Benj Pasek and Justin Paul), it is perhaps surprising he has screenwriting credits on shows such as Curb Your Enthusiasm and The League, plus one 2011 episode credit for The Simpsons. But music is his first love — he studied classical piano from the age of six, and began composing music at 10.

Hurwitz is often associated with jazz, which is ironic since that is not his background. Blame Chazelle — Hurwitz had to learn the grammar of jazz, beginning with their 2009 short film Guy And Madeline On A Park Bench, which is heavily influenced by the world of jazz music and is the precursor to La La Land. “I don’t get considered for that much because people think of me as a jazz person,” he says. “I don’t get offered [other kinds] of scores.”

Hurwitz, who works solo without an assistant, has chosen a low-volume business model. He would rather do fewer projects in order to spend three years on a score in the hope it would have a life beyond the movie. Part of that is being able to travel around the world conducting live La La Land concerts. Whiplash is now part of that repertoire, having been turned into a concert, with the first shows debuting last autumn in North America and then South Korea. Even First Man — which did not earn the same awards attention that greeted their first two features — continues to perform well across all online music platforms, he says.

Next up is La La Land the Broadway musical, which is being written by Pulitzer-winning playwright Ayad Akhtar and theatre director Matthew Decker. “I know nothing about it [yet],” says Hurwitz, who only found out about it a few days ahead of the announcement in February. “I don’t know when I will get started [but] I feel like Lionsgate wants us to move quickly. I will do the music; it will need a lot of new music.”

Roaring Twenties, with a twist

Babylon, which has earned Hurwitz his second Oscar nomination for original score and his fourth overall, is a raucous romp starring Margot Robbie, Brad Pitt and Diego Calva, set in a nascent Hollywood studio system transitioning from silent films to the talkies.

Wild is a word that comes to mind, even from Hurwitz, when talking about the story and especially the music. Chazelle, who began writing the script over a decade ago after coming across little-known facts about the era, had an across-the-board brief for the craft departments: keep everything grounded in the 1920s but make it nothing like the 1920s we are familiar with. That meant no Charleston. “We wanted to create the feeling of these wild, unhinged, hedonistic parties [that Damien found through his research] and give a modern viewer that feeling. But because it is the line-up of a band at a party in the 1920s, have it be believable [that it’s of the era] — a couple of trumpets, couple of trombones, three saxes, but we are using them in ways that are not at all what we think of as 1920s jazz.”

The duo often turned to rock ’n’ roll as a reference. Rock is most often built around repetitive guitar riffs, and Babylon uses a lot of riff-based music and repetition played by an entire horn section in unison or in unexpected ways.

“It’s very muscular,” says Hurwitz. “It’s not the way horns were used in the ’20s. We took a page from rock in that sense. And we took a lot from modern dance music, [where] beats will drop to give you that moment where the pounding kick or high hats come in. I used horns to mimic the feel you get from EDM [electronic dance music] with that slow rise that raises the temperature and throws you into a new section, the beat or bass dropping. A lot of the structural tricks that are in modern dance music we did with instruments of the day.”

While much of his scoring process was similar to La La Land and Whiplash — a lengthy development and pre-production, pre-records prior to shooting, on-set supervision, and then a year of composing simultaneous to picture edit — Hurwitz also opted for a new technique: sourcing specific musicians to fulfil particular styles and sections of the score.

“I have never made finding the right musicians so much a part of my process in the past,” he says, explaining that music contractors generally fill the band with the best available talent. But trumpeter character Sidney Palmer (Jovan Adepo) has his own storyline in Babylon, so Hurwitz felt it was important to bring in musicians whose styles could complement what he was trying to accomplish with the score. “I didn’t know Sean Jones… I went searching on YouTube. It’s not like I discovered him, he is a well-known trumpeter,” he says, regarding the performer hired to play Sidney’s trumpet on the score. “He lives in Baltimore, has a busy touring schedule, teaches at Peabody, but I was like, ‘That’s the kind of fiery solo trumpet that sounds like Sidney to me.’”

Hurwitz also hired saxophonist Leo Pellegrino, whose viral videos of him dancing in the New York subway while playing saxophone caught his attention. “He has this biting, unique sound and he plays dance music on a sax, which was the kind of music I had been demoing [for Babylon].”

After auditioning a slew of amazing but traditional sax players, Hurwitz hired Jacob Scesney to play the solos at all the parties. “He would be wailing and screaming with the sax, doing overtones and wild things that were just perfect and I learned how to build the pieces around his solos to incorporate him the right way.”

Hurwitz likens the process to recording an artist’s album. “Film music is normally on a really tight schedule,” he says. “This was a few years of just trying different musicians, different things, to find all that special flavour that comes from special musicians and special approaches to particular pieces.”

![The Brightest SunScreen[Courtesy HKIFF]](https://d1nslcd7m2225b.cloudfront.net/Pictures/274x183/3/5/0/1448350_thebrightestsunscreencourtesyhkiff_312678.jpg)

No comments yet