Samuel Maoz delivers a powerful follow up to Lebanon, which won the Golden Lion in 2009

Dir/scr. Samuel Maoz. Israel/Germany/France/Switzerland. 2017. 114 min

Back on the Lido where he collected a Golden Lion eight years ago for his debut feature, Lebanon, Samuel Maoz delivers a shattering portrait of a family grieving the death of their son in Foxtrot. Bound to prove a prime choice for festivals and art house around the world as indicated by its initial launch back-to-back in Venice, Telluride and Toronto, Foxtrot can count on solid critical support which should help woo viewers, given the disturbing but restrained, intimate tone which is never deflected all the way through, from the very first to the last shot of the film.

Moaz pares his dialogue down to the essential minimum, allowing most of the impact to be delivered visually

Assembled like a complex puzzle, each piece painstakingly fashioned with obsessive care and admirable economy, structured like a three-act tragedy with brief prologue and epilogue bookends, Maoz’ film starts with an announcement of a death foretold and ends with the death itself. The plot moves from the comfortable Tel Aviv home of the Feldman family to a remote checkpoint in the middle of nowhere and then back to the Feldman home for the final unravelling. Though it is all about mourning and loss, Maoz’ script reaches way beyond, unveiling in each one of his leading characters deep layers of past guilt that might have never been revealed in normal circumstances.

Michael Feldman (LIor Ashkenazi) is a busy and successful architect,while his wife Daphna (Sarah Adler), had studied philosophy before she got pregnant. Their son Jonathan (Yonathan Shiray), is serving in the Army, and they also have a daughter Alma (Shira Hass), usually too busy with her own things to even pick up the phone. A typical upper class, well-to-do family, they live in a spacious, modern Tel Aviv flat with the entire city skyline picturesquely spread out under their windows.

Then, one morning, the bell rings. Daphna opens the door to find two men in uniform and a female soldier standing there, and before they can utter one word, she faints. For like any other Israeli mother, she knows the only kind of tidings such a delegation bears. It means her son has fallen in what is officially called “the line of duty”.

And this is only the beginning. Going into any further details about the plot would be both unfair and damaging to the film and probably unnecessary. The ensuing first act and the third one are entirely dedicated to the mourning parents, to the terrible shock they experience, unwarranted and yet always nagging in the subconscious of every parent with a son in the Army. Maoz details their confrontations not only with the people around them, ranging from politely compassionate to demonstratively emotional, but mostly with each other and with the secrets they had never fully dared to reveal beforehand.

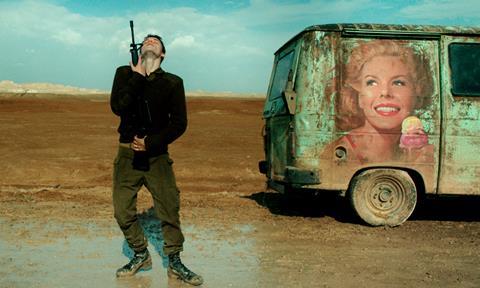

The second act is all about Jonathan and his small unit, the checkpoint they man on an abandoned road, where a solitary camel is their most frequent visitor. When they are on duty, they are supposed to inspect every single car that passes by from and into the occupied territories, and ascertain the identity of each person in it. Off duty, they sit in a ramshackle, rotting container, gradually sinking into the mud, which serves them as both living and sleeping quarters. One single terrifying incident blows their dull, unpleasant routine to smithereens, leaving them all in a state of shock. It is this incident which contributes the picture’s most explicit political reference, by suggesting that neither the gruesome facts themselves nor the manner in which they are dealt with by the military, are in any way exceptional.

Giora Bejach’s camera, meticulously measuring every single angle and travelling motion, every frame and shade of color, provides such eloquent images that Maoz, with the support of a subdued but highly sensitive score,can afford to pare his dialogue down to the essential minimum, allowing most of the impact to be delivered visually, whether it is the sheer despair of parents who can’t find the right words to express their pain or the black humour of the situation.

Seasoned veterans Ashkenazi and Adler, most of the time speaking barely above a whisper, make every single word, every look in their eyes and every bit of body language count, in what may be arguably some of the best work they’ve ever delivered on screen. As for the straightforward, natural, unpretentious demeanor of inexperienced Shiray playing their son, it provides just the right contrast between the two generations.

Production Companies: Pola Pandora Filmproduktions GmbH, Spiro Films, A.S.A.P. Films, KNM

Producers: Michael Weber, Viola Fügen ,Eitan Mansuri, Cedomir Kolar, Marc Baschet, Michel Merkt

International Sales: The Match Factory, info@matchfactory.de

Cinematography: Giora Bejach

Editing: Arik Lahav Leibovich, Guy Nemesh

Production Design: Arad Sawat

Music: Ophir Leibovitch, Amit Poznansky

Main Cast: Lior Ashkenazi, Sarah Adler, Yonatan Shiray, Gefen Barkai, Dekel Adin, Shaul Amir, Itay Axelrod, Danny Isserless, Itamar Rotschild, Ro’I Miller, Arie Tcherner, Yehuda Almagor, Shira Haas, Karin Ugowski

No comments yet