Dir/scr: Ben Lewis. UK-Spain. 2013. 89mins

Taking its title from futurist author H.G. Wells’s 1937 essay World Brain, this well-constructed, though conventional documentary explores the efforts of tech giant Google to create a massive digital library by scanning millions and millions of books, fulfilling the promise of a “universal library.”

The documentary convincingly points out that Google’s ambitions aren’t entirely philanthropic, but meant to continue to improve their Search algorithms, and find ways to monetise their enormous stores of information.

Although largely staid material, veteran documentary filmmaker Ben Lewis (The Great Contemporary Art Bubble, Hammer And Tickle: The Communist Joke Book) manages to raise intriguing questions about the future of books and the corporate control of information in the Internet age.

Co-produced by European broadcasters such as the BBC and ARTE/ZDF, the documentary is perfectly suited to television showings and film festival play, as it is told efficiently and studiously, though not exactly reaching the level of dystopian sci-fi that it likes to reference.

The film puts Google’s massive endeavor to digitise some 10 million books in historical context, tracing such age-old undertakings to create biblio-Meccas from the Library of Alexandria in Ancient Egypt to more recent efforts such as the Guttenberg Project, Wikipedia, and Brewster Kahle’s Internet Archive.

Smart talking head interviews with the likes of Harvard Library director Robert Darnton and University of Oxford’s head librarian Reginald Philip Carr offer astute background information about Google’s plans, while technology thinkers such as Russian author Evgeny Morozov and blonde dread-locked virtual reality pioneer Jaron Lanier raise concerns about what’s problematic: Is Google a social reformer or a maleficent Big Brother; are they power-mongering monsters, or working on behalf of the public good?

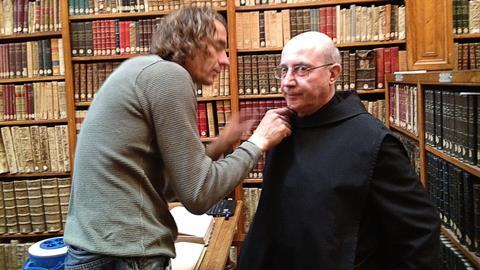

This is the main conflict in Google And The World Brain, and it gets played out among its subjects in some surprisingly effective moments. In one instance, smiling Google Sr. VP Amit Singhal speaks as if he’s drunk the Google kool-aid, testifying to the company’s beneficence. In another scene, an interviewer asks a Spanish monk whether it’s okay if Google is making money on the more than 20,000 books they’ve copied from his Monastery, and he’s struck dumb for a full five seconds, seemingly unable to grapple with the crass commercialistic side of Google’s mission.

Indeed, the documentary convincingly points out that Google’s ambitions aren’t entirely philanthropic, but meant to continue to improve their Search algorithms, and find ways to monetise their enormous stores of information.

Eventually, the film chronicles the pushback against Google, first from authors and publishers of copy-written materials, and more amusingly, from an international community that feels threatened by the California-based conglomerate. Jean Noel Jeanneney, former director of France’s National Library, for example, delights in recounting how he scoffed at Google’s young suits, while Heidelberg University professor Roland Reuss gets in one of the best jibes at the company, criticising them for acting “illegally on such a massive scale that it appears legal.”

The story comes to a head with a landmark international court case against Google, which resolves, in part, some of the documentary’s central disputes.

Director Lewis tries his best to enliven the legal and theoretical debates with an ominous sci-fi sound design and score, digital animated images of exploding books, and silly faux-archival footage of H.G. Wells (an actor, of course) reading aloud from his essay. Such stylistic elements sometimes feel forced, as does the film’s occasionally more apocalyptic tone.

While the documentary makes a final push for H.G. Wells’ dystopic words: “There is no way out, or round, or through,” Google And The World Brain actually suggests there are plenty of end-rounds to Google’s power grabs, such as nonprofit endeavors launched in the wake of Google Books, including the Digital Public Library and Europe’s Europeana project. While tales of corporate takeovers of global knowledge may make for compelling sci-fi, perhaps the actual situation is not that scary, after all.

Production companies: Polar Star Films, BLTV

International sales: Films Transit, www.filmstransit.com

Producers: Bettina Walter

Executive producers: Carles Brugueras

Cinematography: Frank Lehmann

Editor: Simon Barker

Music: Lucas Ariel Vallejos

Website: www.worldbrainthefilm.com

![The Brightest SunScreen[Courtesy HKIFF]](https://d1nslcd7m2225b.cloudfront.net/Pictures/274x183/3/5/0/1448350_thebrightestsunscreencourtesyhkiff_312678.jpg)