Dir: David France. US. 2012. 120mins

How To Survive A Plague is a time capsule that revisits the early days of AIDS activism in the US, when gay groups took to the streets and occupied buildings as they pressured politicians and pharmaceutical companies to work for a cure.

How To Survive A Plague looks and feels like an unruly collage that is anything but conventionally cinematic.

The documentary by David France, a journalist covering AIDS since the 1980s, has the expositional straightforwardness that should lead it right onto public television in the US, although its prefiguration of the current Occupy Movement could put it in an arthouse theater or two before going on the small screen in the US. European television could also seize on its rich archival view of gay history. The film is sure to have an educational market.

France surveys a nine-year period (1987-96) of the campaign fought by activists to influence research into HIV treatment. The doc advances year by year, examining the growing HIV infection rate of the epidemic that activist/playwright Larry Kramer calls a plague. When health officials and pharmaceutical companies stalled, activists found ways to deny them the option of doing nothing. The wild tactics got attention in the US, and spread worldwide. That energy helps keep How To Survive A Plague from being a martyrology.

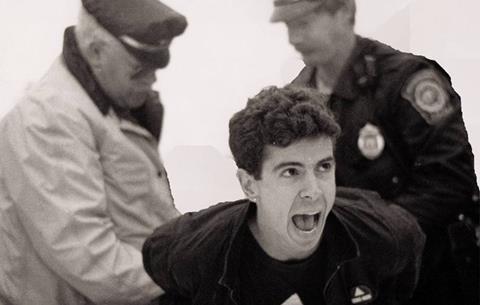

In this poignant chronicle, images keep repeating of young inexperienced and infected men piling into politicians’ offices and blocking traffic. Many died before any progress was made. Many were saved by drug research that their protests helped accelerate. The film estimates lives saved at 6 million. Interviews with those who lived through the protests bring back grim memories — and nostalgia for a time when moral urgency drove their lives.

The film tracks the rise of ACT-UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power), a direct action group responding to perceived inertia from government and from established gay groups. Sharp-elbowed and shrill by design, ACT-UP invaded meetings and conferences on AIDS policy. Its sudden interruption of a mass at St. Patrick’s Cathedral in Manhattan in 1989 made more enemies than allies, but the documentary shows that ACT-UP could not be ignored.

The film’s volume level is high, but out of the shouting came the Treatment Action Group (TAG), a quieter concentration of mostly self-taught activists who persuaded pharmaceutical companies like Merck to include them in the development of new AIDS drugs which proved effective on controlling the virus. Attacked as elitists by many in ACT-UP, TAG helped significant medical achievements to emerge from AIDS activism.

The doc distills thousands of hours of video footage shot by activists themselves on camcorders (new devices then), and preserved at the New York Public Library. Young audiences will discover a generation fueled on anger but short on organization. Older audiences will recall a time when AIDS dominated the media, and conservative politicians like Jesse Helms blamed the victims. (We see ACT-UP’s retaliation, a giant yellow condom suspended outside Helm’s home. Public mockery was a key tactic.)

Most of the film follows a tight format of yearly struggles, complete with mortality statistics, but the volatile emotions of activists from ACT-UP overflow into drama that thrashed in its disorganization and shocked the non-gay population. Young men speak from the heart about fighting battles that they don’t expect to survive. As with many underfunded and outgunned groups, the impassioned protesters fight a lot among themselves.

How To Survive A Plague looks and feels like an unruly collage that is anything but conventionally cinematic. As one activist laments as the AIDS quilt covered the Capital Mall in Washington D.C. in 1992, the AIDS epidemic “should not be the occasion for making something beautiful.” Yet the film reaches a heartbreaking crescendo in archival footage of a demonstration outside the White House in 1992, when protesters fought police to throw ashes of loved ones through the iron bars of the White House fences.

Production values on the doc are high, given the varying quality of footage documenting protests from 1987 to 1996. France has tamed a formidable subject to tell his story.

Production companies: Ninety Thousands Words, France/Tomchin, Ford Foundation/JustFilms, Impact Partners , Little Punk

International sales: Submarine, www.submarine.com

Producer: Howard Gertler

Executive Producers: Joy Tomchin, Dan Cogan

Co-Producers: Henry van Ameringen, Alan Getz, Peggy Farber, Lindy Linder, Ted Snowdon

Screenplay: David France, T. Woody Richman, Tyler Walk

Cinematography: Derek Wiesehahn

Editors: T. Woody Richman, Tyler H. Walk

Music: The Red Hot Organization, Luke O’Malley, Stuart Bogle

![The Brightest SunScreen[Courtesy HKIFF]](https://d1nslcd7m2225b.cloudfront.net/Pictures/274x183/3/5/0/1448350_thebrightestsunscreencourtesyhkiff_312678.jpg)