“Cinema is in a very bad way – I think it’s lost its place,” Brian Cox told the Edinburgh International Film Festival (EIFF) during a surprise appearance in the festival’s industry programme.

“I think it has lost its place, partly because of the grandiose element between Marvel and DC and all of that, and it’s beginning to implode. You’re losing the plot, I think. Television has really stolen the march, when you get incredible things like Ripley, like Succession,” said Cox.

“In terms of the work,” continued the Succession star, referencing films in the vein of Deadpool & Wolverine, “it becomes diluted after a while. You’re getting the same old same old. I’ve done those kinds [of films] – I did X-Men.”

Cox, who appeared in 2003’s X2: X-Men United, said of Deadpool & Wolverine stars Ryan Reynolds and Hugh Jackman: “They make a lot of money out of it. You can’t knock it. But at the same time – the art of cinema [is getting lost]. The art of cinema tends to be more protected in Europe than anywhere else.”

He noted: “Cinema, television and theatre have to reflect who we are, what we’re going through at any particular time. It’s very confused now, but we live in a very confused time. So actually, it’s reflecting the confusion rather well.”

Cox is starting production in Scotland on his own feature directorial debut on August 26, having previously directed for theatre.

Glenrothan is set in a fictional distillery town of the same name and follows two estranged brothers as they are brought back together in an attempt to save their family’s distillery, with Cox and Alan Cumming set to play the brothers.

The project was first announced in 2021, and was developed by UK production company Nevision and Lionsgate.

“It’s a love letter to this country, which I feel is deeply neglected in every aspect,” explained the Dundee-born actor. “It’s become very confused. As a young man, as a boy, I was never very interested in Scotland as such, but as I grow older, I have become more and more interested because of the culture, because of the Celts, because of who we are, what we’ve done, and how we don’t quite get our place artistically.

“We’ve created the Edinburgh festival, we’ve created the Fringe festival, it’s probably the greatest fringe festival ever, it’s like the Olympics and we do it every year. But the homegrown stuff is very, very hard. It’s almost impossible. I felt it was time to come back and honour, not just the country, put the people who work [in it] – the designers, the costume, make-up people, camera people. It’s a question of honouring people, and I’m at a time in my life where I feel I need to do that.”

Casting woes

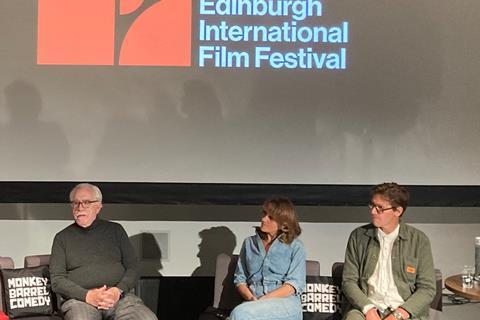

Cox was taking part in a panel discussion exploring the transition of work from live performance to screen, alongside WME Independent co-head Alex Walton, producer Afolabi Kuti and directors Nina Conti and Daniel Reisinger, who both have films world premiering in the EIFF competition. Edinburgh Fringe veteran comedian and ventriloquist Conti directs Sunlight, while Australian filmmaker Reisinger is behind And Mrs.

The change in approach to casting was a hot topic of discussion. “We’ve had a number of movies recently where it’s come to down to the social following of the actor, that’s really made the difference… Their social following, to hit that demographic, is of real value,” said Walton. “That’s what distributors are putting more currency into.”

He continued: “When you’re selling a drama, if you got great reviews it was cheaper to market them because the press were fanning the flames. Now, if you’ve got social following, you’ve got an audience, it’s way more affordable for distributors.”

“It’s crazy when you’re in LA and they do these castings, and everyone has to stand up and start the casting [with]: ‘I have this many followers on Instagram, I have this many followers on Twitter [now X],” added Reisinger.

Cox was irate about the now dominant practice of actors submitting self-taped auditions for parts, as opposed to being able to audition in-person for a casting director – a habit which took over during the Covid pandemic.

“Sometimes they [actors] never even get the fucking result because they get ignored. So they can spend three days making a tape which goes nowhere… Young actors are in a limbo, it’s designed to maintain that limbo. It’s disgusting, quite frankly, because it actually stops what an actor can do or who an actor is.”

No comments yet