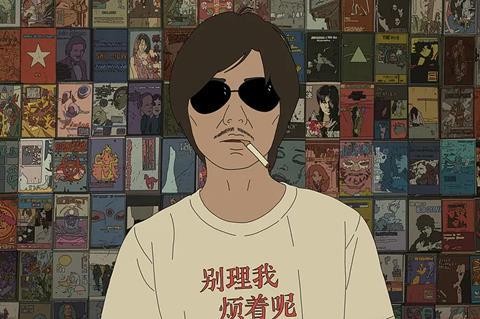

The “surprise film” due to screen in Directors’ Fortnight but was pulled at the last minute is Chinese director Liu Jian’s animation A Portrait Of The Artist As A Young Man. It would have been the only Chinese feature playing at this year’s Cannes Film Festival.

But organisers announced last week the late entry would not be ready in time due to ongoing pandemic restrictions in Beijing.

Produced by Yang Cheng and with a voice cast including Chinese director and Cannes regular Jia Zhangke, the film is set in an art college in the 1990s, taking a bittersweet look at youth drawn from Liu’s experiences as an art student.

As China maintains a zero-Covid policy, with lockdowns in Beijing and Shanghai, post-production facilities are among those to have closed their doors, which may have impacted the completion of the film.

However, Liu previously fell foul of Chinese censors in 2017 with his second animated feature, Have A Nice Day. After premiering at the Berlinale – as the first Chinese animation ever selected to play in Competition – the black comedy was withdrawn from France’s Annecy film festival following pressure from Chinese officials.

Producer Yang did not respond to Screen’s request for comment.

China nearly absent from Cannes

China is represented by just a few short films in Official Selection and across Cannes’ parallel sections this year. Last year, there were no titles in Competition but Wei Shujun’s Ripples Of Life premiered in Directors Fortnight and Na Jiazuo’s Streetwise played Un Certain Regard while Wen Shipei’s Are You Lonesome Tonight? and Zhao Liao’s documentary I’m So Sorry were both in Special Screenings.

Beijing-based sales company Rediance handled two of the titles from last year - Ripples Of Life and I’m So Sorry. ”Censorship is a long and complicated process,” said Rediance CEO Xie Meng. ”When a film is finished, it is required to apply for a number of permits before it can premiere overseas. By the time the festival invite drops, the turnaround time leading to the premiere is extremely short. Now there are more hurdles that we need to overcome, making the whole process longer and more difficult. Time is always an issue. If the official censorship is not fully cleared in time, it will end up like One Second.”

One Second is the Chinese drama, set during the Cultural Revolution and directed by Zhang Yimou, which was selected for the Berlinale in 2019 but pulled from Competition just four days before its world premiere. The same year also saw the withdrawal of Hong Kong director Derek Tsang’s China-set Better Days from the Berlinale’s Generation section.

”There is stricter control over film production and festival distribution at various points in the Chinese cinema food chain,” claimed Toronto-based film programmer Shelly Kraicer, who lived in Beijing for more than a decade. “It is harder or next to impossible to get approval for anything at all controversial. Even things that would have been totally inoffensive to authorities a decade ago are now strictly forbidden.”

Outside of the censorship system, he added: “The grey areas that used to exist that encouraged purely or semi-independent in style Chinese art cinema have systematically been shut down. The Chinese government no longer tolerates such ‘not quite banned but not quite authorized’ grey areas, within which interesting filmmaking used to be able to flourish in a limited way in China.”

For three consecutive years, independent Chinese films won Tiger Awards at International Film Festival Rotterdam (IFFR): Zhu Shengze’s Present.Perfect in 2018; Cai Chengjie’s The Widowed Witch in 2019; and Zhenglu Xinyuan’s The Cloud In Her Room in 2020. Kraicer jointly programmed these three films as a curator for IFFR, until a recent mass layoff eliminated his position.

Kraicer further suggested that medium-to-large budget Chinese films no longer need international festivals. “China has evolved, since pre-Covid at least, into a self-sufficient system combining local festivals, awards, marketing, promotion and ticket sales,” he said. ”In fact there is a negative incentive to premiere outside, given the unpredictably of the film bureau’s control over foreign festival screenings.”

The pandemic has no doubt caused production delays, but also influenced the mindset of filmmakers. “Given the strict travel restrictions, Chinese filmmakers and actors are unable to attend international events, and it is the same for Chinese media. They won’t get the kind of hype and media coverage that they used to get pre-Covid,” said Rediance’s Xie.

This partly explains why some Chinese filmmakers have opted to premiere locally at Shanghai or Beijing film festivals, which may even generate more publicity than from overseas. This is also in line with a more localised focus set by the Chinese authorities, which aim to raise the profile of local events, steering away from foreign endorsement.

Once held biannually, China’s Golden Rooster Awards was turned into an annual event from 2019 when Beijing started to boycott Taiwan’s Golden Horse Awards, and last year, a best foreign language film category was added to its lineup of all-Chinese nominees. The Oscars have also been downplayed, with no telecast in China for the last two years.

In Cannes this year, Rediance represents Argentinian director Maria Silvia Esteve’s short film The Spiral in Directors’ Fortnight. This is part of the Chinese company’s continuing effort to diversify its portfolio, having co-produced Apichaptong Weerasethakul’s Memoria and Anthony Chen’s Wet Season.

![The Brightest SunScreen[Courtesy HKIFF]](https://d1nslcd7m2225b.cloudfront.net/Pictures/274x183/3/5/0/1448350_thebrightestsunscreencourtesyhkiff_312678.jpg)

No comments yet