Hope and optimism were in the air at the annual UK Cinema Association (UKCA) conference this week, attended by exhibitors buoyed by a strong start to the year thanks to the success of Bridget Jones: Mad About The Boy.

But after a challenging five years, it was agreed there was no time to be complacent.

“All of us need to do more than ever,” said Phil Clapp, UKCA chief executive, at the two-day event, which took place under the theme of ‘innovation’ at London’s Picturehouse Central.

Exhibtors packed out the event, representing venues of all shapes and sizes, from the multiplex giants of Odeon and Cineworld, to a representative from one of the UK’s oldest cinemas, North Yorkshire’s Ritz Cinema, now run entirely by volunteers.

Screen reports the key talking points from the event.

The under-25s are turning up

As of March 6, the UK-Ireland box office is up 15% year-on-year, the strongest start since 2020. Up to March 18, this has dropped slightly to being 11% ahead – but this was to be expected, according to Comscore’s executive director Lucy Jones, owing to the Easter holiday falling later in the year, and Disney’s Snow White the only big March release.

The excellent performance of Bridget Jones: Mad About The Boy for Universal, bringing in £42.9m as of March 17, has set 2025 off to what Jones confirmed to be a “strong start”.

Significantly, according to Comscore’s exit polls, 44% of the Mad About The Boy audience were under-25, many of whom weren’t even born when the first Bridget Jones film came out in 2001. Younger people gave higher ratings for the film and were more likely to recommend it, and 24% of the audience had not even seen the earlier films.

And it’s not just Mad About The Boy that’s a cause for celebration. Horror Nosferatu was an unexpected hit, and was the highest grossing film of January, taking £12.7m for Universal. It particularly performed well with the younger demographic, according to Comsore’s exit polls, with 47% of viewers on the opening weekend being under-25.

There has been encouraging diversity among the 10 titles that have contributed £5m each to the box office in 2025. As well as Mad About The Boy and Nosferatu, there’s Disney’s Mufasa: The Lion King, Universal’s Dog Man, Paramount’s Sonic The Hedgehog 3, Disney’sMoana 2, Universal’s Wicked, Studiocanal’s We Live In Time, Disney’s Captain America: Brave New World and Disney’s A Complete Unknown.

‘Bunching’ worry

‘Bunching’ was a phrase used repeatedly. The term relates to a period of time in which a plethora of major films are released in quick succession, leaving gaps in the rest of the year where exhibitors are scrambling to fill slots. This was the case in 2024, in which five of the top 10 best performers at the box office were released in November and December: Wicked, Moana 2, Paddington In Peru, Mustafa: The Lion King andGladiator II.

“In 2024, we had 1114 new titles released into cinemas, 200 of those were saturation releases, meaning they played in 250 or more cinemas, and those are the highest numbers we’ve ever seen,” said Jones. “It’s not a pipeline issue any more, the supply is there, it’s more the spacing of titles that is causing us a little bit of difficultly, especially if you’re running a cinema with one, two or three screens, you don’t want five of the biggest 10 releases of the year to come in a six-week period, you can’t physically play them all.”

In 2025, a similar trend is expected, with many of the big releases coming later in the year. The fourth quarter has Lionsgate’s Michael, Universal’s Wicked: For Good, Disney’s Avatar: Fire And Ash and Disney’s Zootopia 2.

However, participants at the executive roundtable urged distributors to show more courage when dating films in the release calendar – and not give tentpole films such a wide berth. They pointed towards the big problem with Warner Bros’ Joker: Folie A Deux being not so much the disappointing UK-Ireland box office (£10.4m, an 82% drop on Joker’s £58.3m total), but the fact rival distributors ran scared of the release date, giving cinemas no viable alternatives for several weeks.

The roundtable included Walt Disney distribution senior vice president Nick Rush; Matt Smith, head of theatrical distribution at Lionsgate UK; Everyman’s director of film Serena Gill; Showcase Cinemas UK manging director Crispin Lilly; and Tony Mundin, owner and managing director at Manero Cinemas. (The executive roundtable can only be reported by Screen without directly attributing quotes to participants).

Reduced theatrical windows have had a negative impact

The shorter theatrical window is the single biggest factor behind the post-Covid decline in cinema admissions – argued one participant at the executive roundtable.

UK-Ireland box office for 2024 showed recovery from the pandemic but admissions remain roughly 25% down on the pre-pandemic average. Windows have shrunk from 16 weeks pre-pandemic to a flexible window that is typically 45 days for big studio releases.

Exhibitors are relaxed about a quick transition to the home when a film has not worked theatrically, but conversely would like to see the home release delayed when a film is continuing to draw audiences to the cinema. Wicked was cited as a film that transitioned to premium video on-demand at a time when it was still working well theatrically – and participants were divided about the impact on the box office that resulted.

Showtime requirements are too restrictive

Attendees argued repeatedly for more flexibility on showtime requirements – pushing against the convention that a major distributor demands a film to be booked into all showings in a screen in the first week or two weeks of its release, which is difficult guarantee for cinemas with a small number of screens.

“Trying to get the films in when distributors are asking for all shows – Parkway Barnsley has got three screens – just doesn’t work,” said Rob Younger, owner of Parkway Barnsley, during the discussion on elevating the big screen experience. “We’ve had to take off films [ [to make room for incoming releases] that are making good money.”

“That is hurting us,” said one participant in the executive roundtable. “Over the past few years, the key focus for the whole industry is, ‘How do we grow audiences when the slate is lacking?’, which is what exhibition has been doing. And for us, we found success in diversifying, playing more films for longer into their run, more events, more alternative content.

“But that means it’s much harder to bring a film in on all shows, particularly if the goal is to continue growing audiences and drive frequency of attendance. You can’t do that if you’re showing just two or three films, you’ve got to be showing eight to 10 and cater to everybody. Just the flexibility in the show requirements will open that up to hopefully keep both sides happy.”

Some exhibitors have suggested the all showtimes requirement to be limited to opening weekend only, to allow for the greater flexibility needed for smaller cinemas to make the most of diverse programmes.

Will AI take our jobs?

That was a question posed by the final panel of the conference.

“The things you have to worry about is whether AI is taking a job now, soon, soonish, or [you need to] get some help from AI, or you’re fine,” suggested Rich Welch, senior vice president of innovation at Deluxe Cinema. “And to give you a clue, none of you are fine.”

Rob Lea, head of screen content and pricing at Vue Entertainment, explained it was the release of one particular 2011 film that inspired the multiplex exhibitor to explore machine learning when scheduling films in their cinemas.

“Moneyball was a big inspiration for us,” he said. “How can we use analytics to improve decision making?

“A key thing I’d stress is, although it is an AI system, and it’s very impactful to us, it’s very much kind the classic phrase, ‘Garbage in, garbage out.’ It really relies on the human intervention.

“We have a team of experts – film bookers, traditionally – who see the films, forecast the film performance, select comp titles, and all of that is key to go into the system to then help us optimise where the right cinema is to show that film at the right time.”

Community is at the heart of the UK’s cinemas

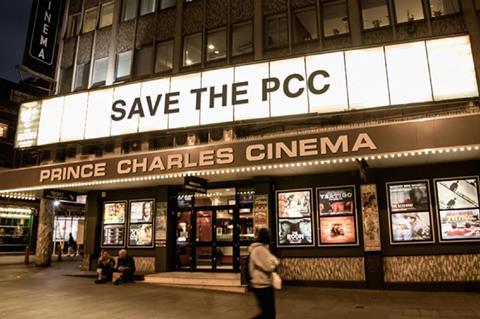

The outpouring of love from cinemagoers at the news in January that London’s iconic repertory Prince Charles Cinema (PCC) was facing an uncertain future speaks to the community spirit that has helped keep the UK’s independent exhibition sector afloat during a tough few years of pandemic woes, rising costs and film pipeline issues, and is one thing AI cannot replicate.

PCC’s landlord insisted a break clause be added to the central London cinema’s contract, which would mean the cinema could be turfed out with only six months’ notice. As of March 20, an online petition support PCC had reached 162,243 signatures.

The conference’s youth panel of east London-based students, curated by charity Into Film, all agreed their favourite cinema was the PCC, and used their platform to ask for more cinemas to programme reperatory titles.

PCC marketing manager Jonathan Foster, talking on a panel discussing innovation and box office performance, said of the cinema’s current position: “It seems there is some movement on possibly coming up with an agreement on the lease, just waiting for lawyers to work it out. I think it’s going to be okay. We’re positive.”

The importance of personal interaction with customers was a key message from panellists who represent smaller circuit cinemas outside of metropolitan areas, who offer tours of projection rooms and have seen sell-outs from eventising around opening weekends.

“Interact, interact, interact, interact” was Parkway Barnsley’s Younger recommendation.

Lewes’ Depot founder-director Carmen Slijpen championed the “congregational experience” cinemas still offer, and at an affordable price point compared with theatres and festivals. “Cinema will not end,” she beamed.

No comments yet