As the UK faced political crisis and internal division, audiences flocked to the cinema in ever-greater numbers for escapism and uplift. Screen reports on a year of admissions growth.

This was a year in which the UK navigated a turbulent political landscape, with the deadline for the country’s exit from the European Union looming and the terms of a Brexit deal still not agreed or finalised in the week before Christmas. Against that unsettled backdrop, however, the country’s cinema industry has had a quite remarkable year.

Admissions and box office declined in equivalent mature markets across the continent, from a modest contraction in Spain to alarming plunges in Germany and Austria. The UK seemingly faced the same challenges: the FIFA World Cup, a scorching heatwave and the ongoing march of Netflix and the streaming giants. But box office was up 3% for the year to the end of November, and admissions were up 5%.

“We are undoubtedly out of step,” comments Phil Clapp, chief executive of the UK Cinema Association, representing the interests of the exhibition industry. “In mature western and southern Europe markets, almost none of them are flat, some are in deficit and some are horribly in deficit.” Clapp points to the level of investment that his exhibitor members have been making in cinemas in the UK, as well as suggesting a possible link between cinemagoing and “the feelgood factor and the need to get away from watching the country tear itself apart on the nightly news”.

An examination of the films that have performed particularly well appears to back up the latter notion. “It seems a bit glib to call it escapism, but it’s clear that musicals and films with a strong music component are having a golden period at the moment,” says Tom Linay, head of film at UK cinema advertising agency DCM. “People get swept up in that genre more than any other types of film, and as a result they’re huge.”

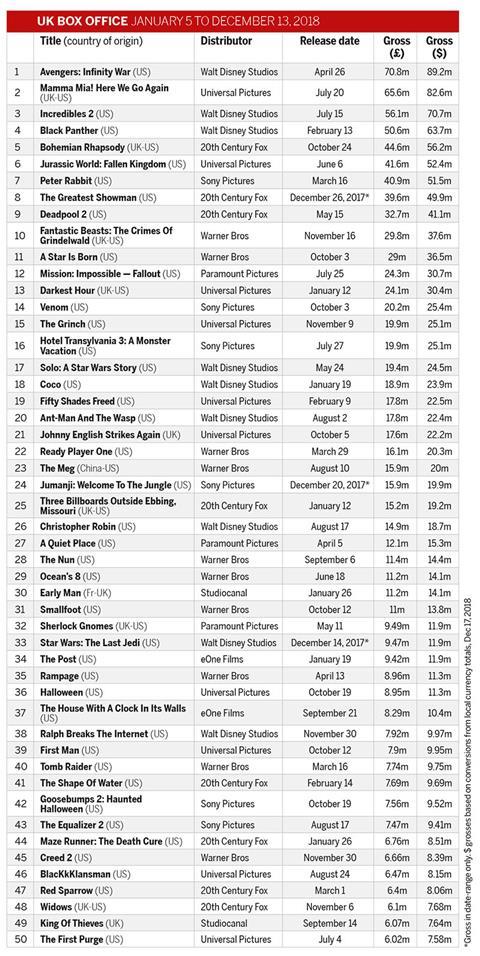

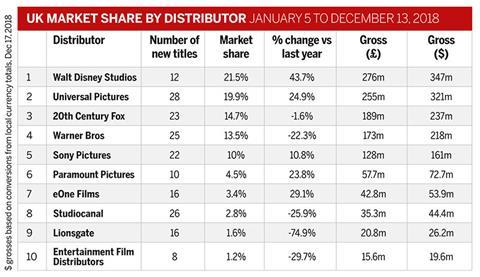

While Linay adds that “the superhero narrative reached a particular crescendo this year”, with the $151m (£120m) combined UK and Ireland gross of Avengers: Infinity War and Black Panther, both those films were positioned to appeal far beyond the traditional fanboy audience. “If you are making a film that you want to be the biggest of the year, you need to appeal strongly to both men and women,” he says.

Indeed, Disney and Marvel’s marketing images for both titles ensured that female characters featured visibly in the mix: Mrs Incredible was the more active character in Incredibles 2; Mamma Mia! Here We Go Again is a continuation of a female-led franchise; and while both Bohemian Rhapsody and The Greatest Showman (the latter a 2017 release that performed robustly in 2018) boast male protagonists, both titles strongly engaged female audiences.

“Going after superhero fanboys or family will take you to a certain level. The breakthrough successes have been those films with a much broader appeal,” concurs Clapp. He also points to the untypically large number of major hits, with seven releases in 2018 cracking £40m — around $50.5m — plus The Greatest Showman also achieving that total within the 2018 calendar year. In 2017, only four titles had surpassed £40m by the middle of December. “In recent years, we’ve had one film that is head and shoulders above the others, be it a Bond or a Star Wars,” adds Clapp. “This year, there is no runaway success but there is a significantly larger number of strong and perhaps unexpectedly strong box-office performers.”

Price wars

In the UK, cinema admissions grew steadily from their 1984 low point, peaking in 2002 with 175.9 million, and have bounced up and down ever since, with 170.6 million in 2017. What has been a constant factor is that box office has always run ahead of admissions, reflecting an annual ticket price inflation boosted by 3D and the growth of premium experiences in either environment or technology.

In 2018, headlines may have been grabbed by the revamped Odeon Leicester Square’s £40 ($50) ticket price, but the overall narrative is in the opposite direction: average ticket prices have actually gone down since admissions have risen faster than box office.

While Odeon has been selectively making over its estate with its Luxe proposition, and the upmarket boutique chains, notably Everyman, have been opening new venues at a rapid pace, Vue has been offering customers an attractive low price at many of its venues — £4.75 ($6) per ticket on Saturday evening in Cardiff, for example. Tickets purchased via Cineworld Unlimited and Odeon Limitless cards are put through the tills at relatively modest transaction values.

“From our perspective it’s a good thing because we work with admissions,” says DCM’s Linay, whose company is in the business of selling eyeballs to advertisers. “Major exhibitors are working hard to push their subscription model, and if they haven’t got one, they’ve got an aggressive pricing strategy. And [two-for-one ticket offer] Meerkat Movies are very happy with their year as well.”

Clapp comments that 2018 is a year “where kids films are particularly strong and where 3D is not particularly strong, and that tends to depress the average ticket price.” But, he adds: “There has undoubtedly been an element of discounting in the market. And that reflects a competitive sector where each company is trying to find a price point that is attractive to audiences. In particular, in areas where there are a large number of cinemas in competition with each other, pricing is one of a number of levers that a cinema may pull.”

The lack of a Star Wars film in 2018, and the release of its nearest equivalent — Mary Poppins Returns — a week later in the calendar, are potential speed bumps for December.

“With 161.3 million admissions to the end of November, we need 14.6 million admissions in December to beat 2002,” says Linay. “And if we beat 2002, then that will be the biggest year for admissions since 1971. At the beginning of the year, looking at the release calendar and anticipating a summer disrupted by World Cup football, we never expected to find ourselves in such a strong position.”

![The Brightest SunScreen[Courtesy HKIFF]](https://d1nslcd7m2225b.cloudfront.net/Pictures/274x183/3/5/0/1448350_thebrightestsunscreencourtesyhkiff_312678.jpg)

No comments yet