Dir: Abel Ferrara. France-Italy-Belgium. 2014. 85mins

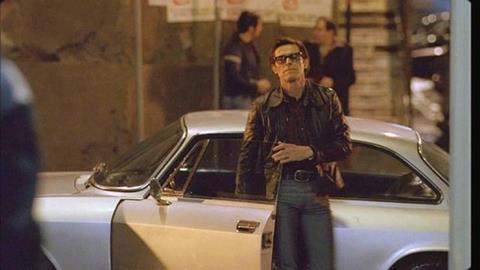

A flawed but intriguing attempt to capture the final days in the life of Italian writer, filmmaker and poet Pier Paolo Pasolini, who was murdered by a rent boy in the small hours of November 2, 1975, Abel Ferrara’s first biopic sees one of indie cinema’s walkers on the wild side in uncharacteristically subdued, contemplative mode.

The Pasolini that emerges is a collection of diverse and sometimes incoherent fragments more than a rounded character.

Sure, there’s a small orgy and some just-glimpsed fellatio, plus a couple of fairly explicit clips from the Italian maestro’s ‘scandalous’ last film, 120 Days Of Sodom, but it’s Willem Dafoe’s impressively understated lead performance that sets the tone of a film that tries to understand a complex man by simply following him through the course of what, but for it’s ending, would have been an unremarkable mid-career day-and-a-half in the life.

Intercut with reconstructions of Pasolini’s life and death over the course of his last 48 hours are dramatised scenes from a novel and film script he was working on at the time. What emerges from an at times confusing mosaic is the portrait of a man who in his creative projects, public declarations and private life was taking a prophetic, apocalyptic turn, shocking the bourgeoisie as he attempted to uncover hidden political-industrial conspiracies that he believed were dehumanising Italian life.

But although it’s a surprisingly absorbing watch, this uneven film never really gets under the skin of the poet. In Gus Van Sant’s final-days-of-Cobain film Last Days this outside view was a deliberate technique, a study in the everyday banality of genius; here the impression is of a series of takes on a character which never quite add up to a whole portrait.

The reaction among the Italians in the audience at the film’s Venice premiere ranged from mild admiration to bemusement to dislike; it probably didn’t help that the characters speak English part of the time and Italian at other points, for no obvious reason (though this will presumably be fixed by dubbing for an Italian release). Outside of Italy, Pasolini will most likely be confined to the more resilient end of the arthouse market; it certainly has none of the topicality or controversy-value of Ferrara’s last feature, Welcome to New York.

Two interviews given by Pasolini in his final 48 hours are restaged here, and help to chart the mindset of an intense intellectual whose thinking was veering towards a sort of Book-of-Revelations Marxism, warning darkly that “we are all in danger” but at the same time nailing the rampant materialism that would indeed come to characterise Italian and global life after the demise of the age of ideas. We see the poet-director, back from a conference in Stockholm, return to the house in Rome he shared with his devoted mother (veteran Adriana Asti) and cousin-secretary Graziella (Colagrande).

Another cousin, Nico Naldini (Mastandrea), comes across as his literary agent in a film that is sparing on who’s-who explanations. Maria de Medieros also shows up in an excessively mannered turn as Pasolini’s long-time friend and later literary executor Laura Betti. Later, Pasolini goes out to dinner with actor-turned-friend Ninetto Davoli (Scamarcio), before picking up rent boy Pino Pelosi (Tamilia) and heading for the seaside wasteland near the resort of Ostia where he would meet his end.

The film’s version of the murder itself takes on board the by-now generally accepted idea that Pelosi was not alone in carrying out the crime, but (perhaps wisely) leaves it up to the audience to decide whether the thugs who join the then 17-year-old rent boy in the brutal attack were violent homophobes or far-right thugs sent by men in high places. To focus too insistently on the crime itself (like Marco Tullio Giordana’s 1995 film Pasolini: An Italian Crime) would detract from a film that is not an investigative thriller but an attempt to create a cinematic ‘heatmap’ of a dark, creative soul at a point of crux.

Central to this structure are scripted and staged scenes from the two works Pasolini was working on at the time: a rambling novel called Petrolio, mixing rent-boy fantasies with the dirty politics of the oil industry, and a script for a film in which a Roman character called Epifanio (played by the real Ninetto Davoli) and his servant (Scamarcio again) follow a miraculous star to the birth of the Messiah, via the land of Sodom, where they turn up on the one day of the year when the exclusively gay male and female inhabitants couple with each other in order to ensure the survival of the race. Ferrara seems to have let the spirit of Italo giallo and peplum soft porn circa 1975 rub off on the staging of this airbrushed bacchanalia.

The Pasolini that emerges is a collection of diverse and sometimes incoherent fragments more than a rounded character. But perhaps that’s the point Ferrara and scriptwriter Bracci are trying to make: that the closer you get to the enigma of an intensely private public man, the more he slips away.

Production companies: Capricci, Urania Pictures, Tarantula, Dublin Films

International sales: Funny Balloons, contact@funny-balloons.com

Producers: Thierry Lounas, Conchita Airoldi, Joseph Rouschop

Executive producers: Camille Chandellier, Costanza Coldagelli

Screenplay: Maurizio Bracci, based on an idea by Abel Ferrara and Nicola Tranquillino

Cinematography: Stefano Fallivene

Editor: Fabio Nunziata

Production designer: Igor Gabriel

Main cast: Willem Dafoe, Ninetto Davoli, Riccardo Scamarcio, Valerio Mastandrea, Adriana Asti, Maria de Medeiros, Roberto Zibetti, Giada Colagrande, Damiano Tamilia

![The Brightest SunScreen[Courtesy HKIFF]](https://d1nslcd7m2225b.cloudfront.net/Pictures/274x183/3/5/0/1448350_thebrightestsunscreencourtesyhkiff_312678.jpg)