Sinead O’Shea’s spirited documentary is a fitting tribute to Irish author Edna O’Brien

Dir. Sinead O’Shea. Republic of Ireland/UK, 2024. 98mins

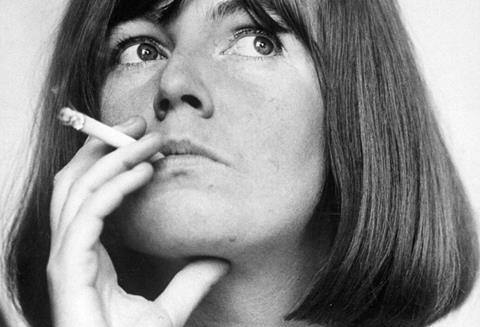

Blue Road seems a far more fitting tribute to Edna O’Brien, her life and work, than the gushing epitaphs delivered on the Irish author’s death last year at the age of 93, when the establishment was finally overcome by her genius. Sinead O’Shea’s warm, empathetic documentary recounts the turbulence of being O’Brien through a mixture of her own words and those closest to her, including her two loving sons. Sometimes words just aren’t enough to capture a life so uniquely lived and expressed, though, and Blue Road searches to capture the light between them. It’s executed in the same spirit of openness and friendship that O’Brien brought to her own headlong passions and you get the feeling that, yes, she’d think it got her right.

An arresting portrait of what makes an author

O’Brien told her own story in late-life autobiography The Country Girl. Blue Road brings it vividly to life – and beyond the end of that book, to her very last days. The timelieness of this project should work in its favour when it comes to festival exposure after a TIFF world premiere.

O’Shea’s access to archive footage enhances the film, including scenes of O’Brien’s mother and father, still living on the farm long after she left, bemused by her fame (or infamy). O’Shea, director of A Mother Brings Her Son To Be Shot and Pray For Our Sinners, knows how to put imagery like this o best use, judiciously blending bucolic scenes with sound and interviews to create a documentary which isn’t as conceptual as Errol Morris’s view of John le Carre in last year’s The Pigeon Tunnel, but is a similarly arresting portrait of what makes an author. Jessie Buckley lends her expressiveness to O’Brien’s diaries, never before voiced

O’Brien’s story, like that of le Carre, starts in a troubled home and pretty much ends there too, at least in her mind. O’Brien’s overwhelming urge was freedom: from Ireland’s draconian mores of the 1950s, from an impoverished ‘big house’ in the one-horse village in County Clare with 27 pubs, her father’s drunken rages and the glares of the neighbours. Even in Dublin, training to be a pharmacist, she couldn’t escape. Falling in love with the austere, much older (by 16 years) and eventually bullying author Ernest Gebler, she eventually fled to London and never returned to Ireland to live, although the country haunted her work for the next seven decades.

She only got to London after escaping an attempted kidnap by her father involving the parish priest, angered by her ‘taking up’ with a divorced man. Gebler, in his own time, would also try to curtail her ambition. Although he introduced her to her publisher, the runaway success of The Country Girls trilogy drove his jealousy to ugly heights and their eventual divorce was bitterly contested. He also claimed to have authored her work.

The nastiness would continue: in Ireland, it came from the church, the establishment (at one point, all her books were banned) and the country’s all-male literary and critical circles. Elsewhere, she had a feyness which was mocked. Her tendency in the 1970s to open her house to celebrities – and her mind, to acid – let to her being dismissed as insubstantial. A lengthy affair with an unnamed politician robbed her of her voice. She considered committing suicide in the late 1980s, after yet another critical mauling.

You can see In Blue Road, though, that Edna O’Brien never let all this change or harden her. She was a singular talent, a maverick, who remained defiantly herself, only looking to her beloved Joyce for lessons. The 1972 Longford report on pornography called her a “purveyor of insidiously pornographic and perverted views on sex”. Yet she wrote about political matters too, and was hammered. Books about a rape victim, or a serial killer, all received a public drubbing. And although her name became a byword for liberation, she co-existed uneasily with feminist thinking of that time, with her early characters always yearning for love but often achieving victimhood.

O’Brien spoke as she wrote, in a highly poetic but ultimately very grounded manner. She liked champagne and she spent all her money. She just never fitted in with what people thought she should be. For the woman who so famously sought love, she ended her life without a partner, without much money and in a rented house. But certainly, as the clear-eyed testimony of her two sons asserts, not without the riches of family adoration. What drove her? It’s so interesting to watch O’Brien talk to O’Shea in her very last days, frail and dying and, in her mind, back in the farmhouse again, looking to her father.

Production company: SOS

International sales: Submarine, info@submarine.com

Producers: Claire McCabe, Eleanor Emptage, Sinead O’Shea

Cinematography: Eoin Mcloughlin (UK), Richard Kendrick (Ire)

Editing: Gretta Ohle

Music: Richard Skelton, George Brennan, Gareth Averill

Narration: Jessie Buckley