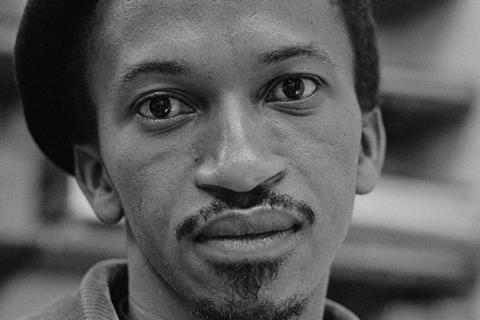

Raoul Peck explores the life and work of exiled South African protest photographer Ernest Cole

Dir/scr: Raoul Peck. US. 2024. 105mins

At the heart of Raoul Peck’s latest documentary Ernest Cole, Lost And Found, a stirring lament of the exiled South African photographer, is the devastating image of a life deferred. Living at the debilitating height of apartheid, Ernest Cole quickly shot to fame with his rebellious book of photographs ’House of Bondage’ (1967), which captured the unvarnished sights of racism, segregation and the realities of Black life in his home country. To publish the book, Cole had to move to America – and never returned to his homeland again. Peck’s film is a rich chronicling of Cole’s unique career, peerless artistry, political strength and moving end.

The concealment of his snapshots mirrors the obliteration of the creative spirit he experienced in his later life

This absorbing text is world premiering in Cannes (special screenings) and, while Peck’s latest recalls his previous films about Black revolutionary figures such as the Oscar-nominated I Am Not Your Negro and Lamumba, this might be the most tender of his works. Peck has crafted another timely documentary which should spark conversations about the crushing impact of intolerance and, with Academy Award-nominated actor LaKeith Stanfield delivering a palpably defiant narration, Ernest Cole, Lost And Found should be a tempting prospect for international distributors. Magnolia Pictures already holds North American rights.

Born in 1940 in Eersterust Pretoria, South Africa, Cole spent much of his early years despising the rampant inequality bred by apartheid. In the film, he describes the indignity of Black people forced to work as domestic helpers, nannies, or in service jobs to racist white employers. He also shares the restrictiveness of ’reference books’: small identification folders, required by law for Blacks to work and navigate the country, that could be seized by nefarious white policemen without warning. In the face of such practices – and much like African American photographer and filmmaker Gordon Parks – Cole made the camera his weapon of choice.

Cole rose fast in the photography world. He was employed by Drum Magazine, gaining the necessary experience to embark on the ’House Of Bondage’ project that would bring him fame. Cole spent the better part of a decade photographing the horrifying images of apartheid and its effects on housing, education, and employment. Many of these delicately curated images—such as the snapshots of ‘Europeans only’ signs—are jaw-dropping. Peck highlights one photo of a white policeman questioning two Black children and allows Cole’s words to describe the emotion that might be playing out on each subject’s face, from the victimised kids to the puzzled onlookers. It’s a microanalysis of art that pays dividends, although it’s disappointing that Peck only uses the approach once.

Cole died in 1990, and Peck has built a working script through his own writing and testimonials offered by friends and family. This allows Cole to speak, through Stanfield’s serious voice, about the entirety of his physical, emotional, and psychological journey following the release of ’House of Bondage’ (the book was banned in South Africa, as was he). Like many Black thinkers, he was immediately pigeonholed into taking on only Black subject matter. Cole, in fact, recounts the dissolution he felt after arriving in New York City in 1966 and seeing the incredible racial promise and sexual freedom, only to discover, during a failed photojournalistic sojourn through the Southern states, that America wasn’t all that different from South Africa. Black people were still expected to stay in their place.

Peck is deeply taken by Cole’s loneliness, his feelings of isolation. Cole was othered by racist whites, and felt separated from Black Americans due to being a foreigner. Peck digs into the loss that happens when you are without a country and a community through Cole and the other South Africans exiles, such as singer-songwriter Miriam Makeba, who fought against apartheid in the strange new land they now called home. Cole would later venture to Sweden, Denmark and England, searching for his artistic place in the world.

The film’s greatest treasure is thousands of previously-lost 35mm negatives that were recently turned over to Cole’s nephew Leslie Matlaisane (the documentary’s lone talking head). These photos are time capsules of specific moments in New York City’s history—from parades to everyday street scenes—and an eye-opening look at Cole’s creative growth and his mental decline; he moves from framing scenes of rebellion and protests to taking an interest in the downtrodden and homeless. With each frame captured by Cole, an increasingly sorrowful refrain is repeated by him: “I’m homesick. And I can’t return.” Before long the zippy cascade of photos, scored to woozy jazz instrumentals, becomes a noticeable drip. Cole stops taking pictures.

Eloquently edited and structured, Ernest Cole, Lost And Found becomes both a heartbreaking elegy to the photographer, and a kind of mystery. The latter arises when Cole’s lost work is found in a Swedish Bank vault without any record of who put it there. The concealment of his snapshots mirrors the obliteration of the creative spirit he experienced in his later life. You come to realise that Cole and viewers were robbed. What other creative statements were left underdeveloped, unspoken or erased because systemic racism refused to allow him back home? What great movement could have happened? Ernest Cole, Lost And Found mourns the pictures and the man left unseen.

Production companies: Velvet Film, Arte France Cinéma

International sales: MK2 Films, intlsales@mk2.com

Producers: Raoul Peck, Tamara Rosenberg, Olivier Père, Rémi Grellety

Cinematography: Moses Tau, Wolfgang Held

Editing: Alexandra Strauss

Music: Alexei Aigui

![The Brightest SunScreen[Courtesy HKIFF]](https://d1nslcd7m2225b.cloudfront.net/Pictures/100x67/3/5/0/1448350_thebrightestsunscreencourtesyhkiff_312678.jpg)