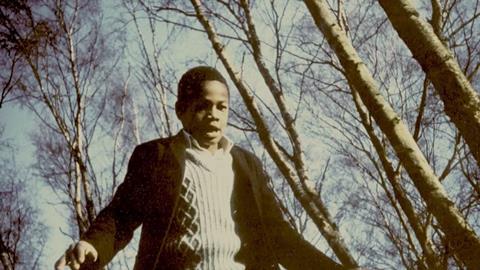

The tragic story of the late footballer Jusin Fashanu and his sibling John recalls a homophobic, racist Britain of the 1980s

Dirs. Adam Darke, John Carey. UK/US, 2017, 80 mins

Early on in the somewhat jumbled, always shocking story of the British premiere league footballer Justin Fashanu and his brother John, who played for England, there’s a reference to his life being surreal. That’s no outsize claim. It’s hard to reconcile the extremes of racism and sexual prejudice in the early 80s with today’s Britain: but then again, Justin is still the only professional footballer to have come out as being gay while still playing, and he’s dead by his own hand, so perhaps times haven’t changed that much. Pictures of him with, amongst others, Paul Gascoigne, hint at other tragic documentaries yet to come.

Who knows what happened to these “fast black boys” on their way to fame and fortune, but they were certainly both deeply troubled by the time they arrived.

Justin’s story isn’t straightforward, it’s not a morality tale with a clear hero, although there are plenty of villains. It wasn’t a simple case of him being gay, or black, or fatherless, sent to the orphanage Barnardos by his impoverished mother along with his brother John, another tricky customer. Ultimately, they were fostered by an older white couple in a tiny Norwich village, never really understanding why their other siblings stayed at home. Who knows what happened to these “fast black boys” on their way to fame and fortune, but they were certainly both deeply troubled by the time they arrived.

Directors Adam Darke and John Carey have a lot on their hands here: their story of a man for whom there “was never peace” is a restless piece of work in itself. As far as the documentary side of Forbidden Games is concerned, they’ve assembled an impressive roster of witnesses, including John himself, to deliver succinct and damning testimonies, and this documentary will be a must-see for British footballing fans. Yet they’ve also made a decision to thread Dreams Of A Life-style re-enactments with young actors through what’s an already busy piece, somewhat diluting the impact of this Cain and Abel story.

Pearl Fashanu, the boys’ mother, is interviewed and still, all these years later, is unable to understand why Justin never accepted how she sent the boys to an orphanage after their father returned to Nigeria. There were four Fashanu siblings; by the time they arrived in Barnardos, John had a crippling speech impediment and clung to Justin. In Shropham, Norfolk, where they were fostered, they were the only black boys for miles around. Justin was the more talented footballer, but John worked harder. Playing for Norwich, Justin was showered with racist epithets; banana skins were thrown on the field.

But Justin wasn’t a victim. He was flash, and he liked to splash the cash, a charming, natural talent who was soon bought by Brian Clough’s Nottingham Forest. Clough, a manager much mythologised by the British footballing fraternity, payed the first ever £1m transfer fee for Fashanu, but he was homophobic, Justin liked rent boys and the media and the playboy life, and it ended in tears.

Justin found god, suffered a traumatic knee injury and went to America for surgery; the temperamental John had worked his way up to playing for Wimbledon in the meantime, and, eventually England. From then on, the roles were reversed, and John would show no quarter to his troubled sibling and former protector when the time came: “The closer the blood, the bloodier the situation.”

Justin – “one day he was one person, the next day another person” – was paid a lot of money to come out to The Sun, although John offered him more not to say he was gay in public. He played the media game, claimed to be bi-sexual, indulging in a highly-improbable affair with the Coronation Street actress Julie Goodyear, made allegations against members of Parliament, and when the end came, it was in troubling circumstances involving allegations of sexual assault. John, meanwhile, joined his tormentors. “I wouldn’t want to get changed in his vicinity,” he said of his brother.

Archive clips – editing by John Carey is supple – remind viewers of a divided Britain; and, indeed, if the past is another country, you wouldn’t want to live there. Music by Soren Anderson complements the piece. Dramatic recreations distract more than they add to the sense of what may be possibly a story that’s too big for the screen.

Production companies: Fulwell 73 Productions, Darke Films, Black Sun Media

International sales: The Film Sales Company, Andrew Herwitz

Producers: Adam Darke, John Carey, Leo Pearlman

Executive producers: Benjamin Turner, Gabe Turner

Cinematography: Damian Bradshaw

Editor: John Carey

Music: Soren Anderson