An intimate, revealing interview piece highly recommended to either legend’s fans

Dir. Orson Welles. US. 2020. 131 mins

Film history has not yet had time to make up its mind about Orson Welles’s long-fabled experimental feature The Other Side of the Wind, the reconstruction of which premiered in Venice in 2018. But two years later, here is a fascinating sidebar to the film, which also stands up compellingly in its own right. Hopper/Welles – with direction credited to Welles – is actually an extended conversation between Welles and Dennis Hopper, filmed in 1970. This might suggest the ominous prospect of grandiose torrents of anecdote; instead the film is an intimate, low-key interview piece in which an unusually retiring Welles prods a thoughtful Hopper for his views on life, cinema, art and the condition of America in 1970.

Hugely revealing about a Dennis Hopper very different from the sacred monster he later became, it also shows Welles in generous, avuncular mood. While this is essentially a fireside chat atmospherically shot, Hopper/Welles is recommended viewing for anyone remotely interested in either personality, or in the history of American cinema.

The meeting was shot on black and white 16mm by Welles’s long-serving collaborator Gary Graver (credited as director on the clapperboard glimpsed throughout) during the making of Other Side. In that film, Welles pitted the fading certainties of Hollywood’s old imperilled studio system against the cultural and social changes represented by a new generation of film-makers – and by the 60s youth revolution in general – of which Hopper was a flag-bearer, having enjoyed massive success with 1969 counter-culture document Easy Rider. When he flew from Taos, New Mexico to Los Angeles to meet Welles, Hopper was working on his follow-up The Last Movie, the reception of which would damage his directing career as dramatically as Welles’s own career was derailed in his day - retrospectively giving Hopper/Welles an undertow of tragic irony.

You can’t help wondering whether Welles recognised Hopper as a potential fellow Icarus.

A somewhat confusing, though conceptually suggestive aspect to the film is that the conversation is supposedly happening at a party that features in Other Side, in which Hopper briefly appeared. So while a relaxed Hopper is straightforwardly being himself, Welles essentially plays the role of Other Side’s protagonist, veteran film-maker Jake Hannaford (played in the film itself by John Huston). Hence, occasional phrases like “I, Hannaford” remind us that this isn’t strictly Welles speaking - or is it? Hopper sometimes seems perplexed, and at one moment, Welles has to make a point of stepping out of character.

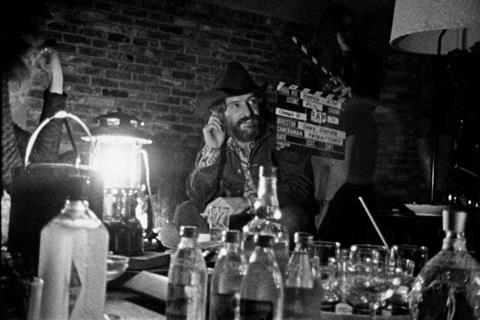

The encounter – set around a low table lit by storm lamps, with two party guests listening in and crew members visibly going about their business - is shot by Graver on two cameras, always trained on Hopper, while Welles remains resolutely off-screen, his voice sometimes muffled by rough sound. Seemingly flowing in real time over two hours plus, although five hours of material were shot, the film shows Welles, with unaccustomed modesty, coaxing out a portrait of the younger film-maker. The result is a Dennis Hopper we may have forgotten ever existed, and that would be eclipsed by his deranged roles in Apocalypse Now, Blue Velvet and many a lesser later movie.

Wearing a Stetson and plucking pensively at his heavy beard, the 34-year-old Hopper comes across as earnest, candid and cheerfully self-deprecating, although a steady supply of drinks gradually brings out his show-off streak. While confessing that he’s not much of a reader, he shows himself to be a studious cinephile, making references to Buñuel, Eisenstein, Antonioni et al, and talks with interest about an odd experimental film he’s just appeared in (in fact, François de Menil’s long-forgotten Crush Proof), improbably co-starring Pierre Clémenti and R&B legend Bo Diddley. While this is anything but a chat show storytelling opportunity, he also has a great story to tell about Elvis Presley’s confusion about how to behave in movies. Hopper is also disarmingly frank about his family background in Dodge City, Kansas, and about his difficult relationship with a forbidding mother whom he confesses he would have liked to sleep with (he later says, “I think I’m a lesbian, really”).

Things get confusing when it comes to distinguishing Orson Welles and the avowedly reactionary Jake Hannaford (presumably it’s Hannaford, not Welles, who hasn’t heard of Bob Dylan). But the conversation takes on a really interesting turn when Welles/Hannaford pushes Hopper on why he isn’t more forthright about his political views, eventually castigating him, “This is the first area in which I find you really weak” – to which Hopper responds with grinning forbearance. You also wonder whether it’s Welles or Hannaford who’s talking about impotence and buying “dirty papers”. In keeping with Other Side, there’s some self-congratulatory banter which suggests that, despite the gap, these two male generations had plenty in common in their attitudes to gender – and indeed, when actress Janice Pennington, one of the two ‘partygoers’ present, tries to enter the conversation in its final stages, she’s barely allowed to finish a sentence.

While the film is a curious footnote to the Welles legend, it’s most revealing about Hopper himself. And it is deeply poignant, given our retrospective knowledge that the current project Hopper describes with such starry-eyed enthusiasm (and it’s only here, really, that he lapses into visionary babble) is fated to stall the career of a golden boy, who would unjustly end up better remembered in the caricatured role of a wild-eyed casualty. You can’t help wondering whether Welles recognised him as a potential fellow Icarus.

Production companies: Royal Road Entertainment, Grindhouse Releasing, Fixafilm

International sales: CAA, nick.ogiony@caa.com

Producer: Filip Jan Rymsza

Cinematography: Gary Graver

Editor: Bob Murawski

Featuring: Dennis Hopper, Orson Welles, Janice Pennington, Glenn Jacobson