Director Dan Reed recognises the material’s inherent sensationalism but commendably avoids any titillation.

Dir: Dan Reed. US/UK. 2019. 236mins

More than justifying its four-hour runtime, Leaving Neverland absorbs as it devastates, shining a spotlight on two young men with damning allegations of how Michael Jackson sexually abused them when they were children. Such a description might make this documentary sound like tawdry tabloid fodder, but director Dan Reed has instead crafted an utterly sobering portrait of abuse — how it happens, how the survivors internalise (and sometimes deny) what happened to them, and what the impact of those lingering wounds can be. While the deceased pop star is never far from the centre of Leaving Neverland, it’s more accurate to say that this is a story of two men, and their families, whose lives were forever shattered.

It’s hard to think of a film about abuse, denial, acceptance and recovery more affecting than this one

Inciting controversy before its Sundance world premiere because of its shocking accusations, the film is set to air on HBO in the States and Channel 4 in the UK. Even ten years after his death, Jackson remains an iconic performer, and between his memorable songs and his infamous personal scandals, he still commands the public’s imagination. So there should be considerable interest in Leaving Neverland, especially in the #MeToo era.

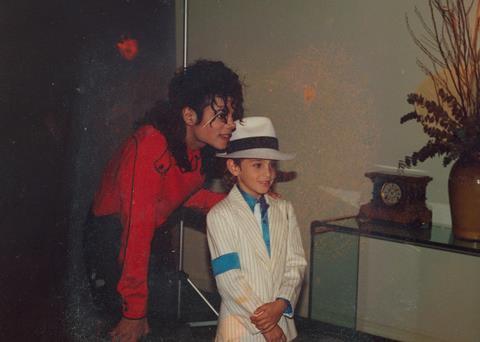

The film introduces us to James Safechuck and Wade Robson, two men who, independently of one another, formed unlikely friendships with The King Of Pop when they were just children in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Safechuck, at age 10, had been in a Pepsi commercial with Michael Jackson, who took an interest in the boy, while Robson got to meet the singer when he was seven, impressing him with his flawless dance moves. In extensive on-camera interviews, the two men — as well as key family members — recount these friendships’ early days and then what happened after they segued into alleged assault.

Reed (a documentarian who has focused on terrorism and, in The Paedophile Hunter, online sexual predators) recognises the material’s inherent sensationalism but commendably avoids any such titillation, opting for a muted, measured tone that allows Safechuck and Robson to tell their stories in sometimes graphic but always candid ways.

Constructed in two parts, each running about two hours, Leaving Neverland wants us to understand why these men (and their parents) were so willing to be seduced by Jackson’s fawning attention. That requires Reed to take his time to lay the foundation for these friendships, recognizing that the singer’s early courtship is crucial because it sets the stage for everything else that follows.

It would be easy for audiences to be judgmental as Safechuck and Robson explain what a big deal it was as aspiring young artists to be taken under Jackson’s wing — to be made to feel special and even loved. But among Leaving Neverland’s remarkable achievements is Reed’s empathetic skill at providing the proper context (usually through archival footage) so that we see the world from the perspective of those boys who were so trusting that they didn’t realise what was allegedly happening to them.

The film could double as a fascinating study of human psychology — particularly, our obsession with celebrities and our inability to see the flaws in people we think we know. Both of these men, as well as their mothers, plausibly reconstruct their thought process, which left them convinced that they could put their faith in Michael Jackson because he was a beloved pop star. But as their tales grow darker, and the accusations more upsetting, what remains riveting is that, on some level, none of these individuals could fully believe that Jackson was capable of such terrible deeds — no matter the legal trouble concerning molestation charges that swirled around him in later years.

Those looking for juicy details of alleged sexual abuse will get their share, but Leaving Neverland is far more concerned with the aftereffects of abuse. Documentaries aren’t criminal trials, but the persuasiveness of Safechuck’s and Robson’s stories is striking — especially as they talk openly about the jealousy, shame, anger and self-loathing that sprung up after Jackson seemingly discarded them. Those thorny emotions extend to the people in these men’s lives, and it’s heart-breaking to learn, years later, how these alleged incidents have continued to drive wedges between different family members.

Composer Chad Hobson does an exemplary job of providing mournful but not hyperbolic musical backing to these shocking accusations, while editor Jules Cornell dexterously weaves between different talking heads so that Leaving Neverland boasts a calm, focused precision that gives weight to the men’s claims. It’s hard to think of a film about abuse, denial, acceptance and recovery more affecting than this one.

Production company: AMOS Pictures

International sales: Kew Media, jonathan.ford@kewmedia.com

Producer: Dan Reed

Editing: Jules Cornell

Cinematography: Dan Reed

Music: Chad Hobson

Featuring: James Safechuck, Wade Robson