Kathryn Ferguson’s striking documentary shines a revealing new light on Sinead O’Connor

Dir. Kathryn Ferguson. UK/Ireland. 2022. 95mins

Here’s the thing about Sinead O’Connor: she was always a heartbreaker, but hers was the heart repeatedly smashed to smithereens. You don’t need to see Nothing Compares, Kathryn Ferguson’s empathetic documentary, to know that the Irish singer has been tormented, and that her stunning rise to fame – and equally rapid fall – between 1987 and 1993 turned out to be a pitiless experience for a young woman, and mother, who had also been an abused child. This tenderly-edited (by Mick Mahon) documentary benefits from O’Connor’s testimony, in voice-over, which wraps around a telescope to an ugly past where a troubled woman was pilloried for speaking up. While we like to consider ourselves a more caring society today, it would be naive to assume her experiences are a thing of the past, making Nothing Compares vital viewing on society’s road to enlightenment; a path O’Connor still travels herself.

Reclaims O’Connor’s rights to her own narrative in a film which ends on a proud note

The very recent death of O’Connor’s teenage son haunts the premiere of this documentary at Sundance. The fact the festival has gone online is possibly provident: the work can reach out without having to be physically addressed in Park City, giving her space. She is such a terrifying mix of fragile and headstrong in Nothing Compares, and even though it catalogues the events of nearly three decades ago, a sense of that vulnerability still permeates the final song she performs onstage that sees the credits out. (This is only time we see her today, or any other contributor, as the film is purely comprised of clips and voiceover, including memorable home video footage.)

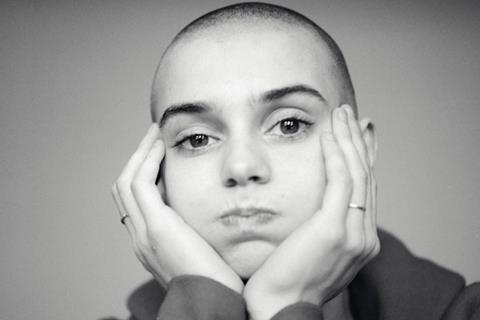

Ferguson’s film starts with O’Connor’s appearance at Bob Dylan’s 30th Anniversary Concert at Madison Square Gardens in 1993, two weeks after she ripped up a photograph of The Pope on Saturday Night Live. The crowd booed her arrival on stage, introduced by the kindly Kris Kirstofferson (“don’t let the bastards get you down,” he says). She looks so tiny, so vulnerable. But O’Connor was never about to be silenced. People remember her, bald and defiant, ripping up the Pontiff’s image on TV, but they don’t recall that she did it to the words of Bob Marley’s ‘War’, with ‘child abuse’ sometimes substituted for ‘war’. Time has vindicated O’Connor but the world couldn’t take it at the time, and her career in popular music was over. The so-called feminist Camille Paglia denounced her, going so far as to say: “In the case of Sinead O’Connor, child abuse was justified.”

From here, Ferguson moves back to O’Connor’s childhood in Dublin, her fractured education and abuse at the hands of her mother. It does not deal with events which took place after that Dylan concert, although audiences will know that her subsequent struggle with mental health has been long and difficult. Even at the height of her fame, with her emotions so much on the surface, it’s often sad to witness O’Connor’s raw talent and rebellious honesty colliding with the world of celebrity – something she had never desired.

Yet Nothing Compares is also joyous, as it tracks her musical emergence and happy times with her first husband John Reynolds (an EP here) and the birth of their child Jake. There’s a strong sense of integrity as she fights her record company’s attempts to sexualise her by shaving off her hair, the shocking revelation that she was urged to have an abortion for the sake of her career, and her life-long sense of responsibility to the women she was educated beside in Ireland’s frightful Magdalen laundries. She loved her mother but her mother abused her, something that perhaps contributed to her devil-may-care attitude to her career and constant ability to be a thorn in everyone’s side, not just the establishment. What did she have to lose, after all?

Prince’s estate refused to allow the production rights to ‘Nothing Compares 2U’, which, ultimately serves Nothing Compares well – the images we do see of the video that accompanied it are enough of iconography. Instead we get the chance to hear more of her other, brilliant self-penned works including the rousing ‘Mandinka’.

It can’t be classified as triumphant but, with Ferguson’s editorial savvy, Nothing Compares reclaims O’Connor’s rights to her own narrative in a film which ends on a proud note. It’s also a reminder of how genuine she has been throughout decades of struggle. To say O’Connor came before her time doesn’t go far enough to describe everything from her look and her spirit, to her honesty and sense of social justice. She has always reached out in times of trouble: perhaps Nothing Compares will help connect her again.

Production companies: Tara Films, Are Mhacha Productions

International sales: Submarine, info@submarine.com

Producers: Eleanor Emptage, Michael Mallie

Editing: Mick Mahon

Music: Irene Buckley, Linda Buckley

![The Brightest SunScreen[Courtesy HKIFF]](https://d1nslcd7m2225b.cloudfront.net/Pictures/274x183/3/5/0/1448350_thebrightestsunscreencourtesyhkiff_312678.jpg)

![The Brightest SunScreen[Courtesy HKIFF]](https://d1nslcd7m2225b.cloudfront.net/Pictures/100x67/3/5/0/1448350_thebrightestsunscreencourtesyhkiff_312678.jpg)