What led Firouzeh Khosrovani’s mother to embrace revolutionary Islam so fervently?

Dir. Firouzeh Khosrovani. Norway/Iran/Switzerland. 2020. 81 mins.

Director Firouzeh Khosrovani (Fest of Duty, Profession: Documentarist) manages to get not just under the skin of her family, but also under that of modern Iran in her spare but inventive and revealing Radiograph of a Family. Khosrovani’s essay film could be described as pre-autobiography, as the history it deals with is less her own - although she figures prominently - than that of her parents, whose relationship is irrevocably transformed by seismic changes in their nation’s history. Premiering in IDFA, Radiograph should attract festival and niche platform slots for its individual and revealing approach to the themes of family relations, memory and women’s social roles.

Incisive and moving clarity

The film begins with a strange statement from Khosrovani: “Mother married Father’s photograph.” This proves to be literally true: Hossein, her father to be, was away in Switzerland when he was due to marry his beloved fiancée Tayi, so told their families to celebrate their wedding without him, pending his return.

Photographs prove the consistent thread both in the couple’s story and in Khosrovani’s approach to it: she narrates their history, and her own, through a wide array of images of the couple and their family, sometimes intercut with home movies and archive footage of Iran, from the 1960s onwards. The story proper begins with the courtship of Hossein – an older, sophisticated, Westernised radiology student living in Geneva – and the inexperienced, religiously observant Tayi. The couple marries and settles in Switzerland, but Tayi dreams of returning to Iran - which they do for the birth of their daughter Firouzeh. Uncertain about her own identity and role in society, Tayi discovers the teachings of religious sociologist Ali Shariati, and becomes passionately involved in the movement that would bring about the Iranian Revolution, distancing her from the altogether secular Hossein.

The couple’s estrangement is exacerbated by Tayi’s enlisting for military action during the Iran-Iraq War and her adoption of strict revolutionary clothing – to the bewilderment of Firouzeh, who wonders why her mother and her friends all dress alike.

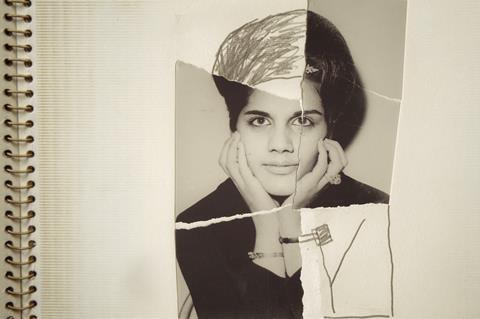

Khosrovani uses an ample gallery of family photos to track the changing relationship of Tayi and the husband she came to call ‘Mousieu’, for his European ways. The photographs have not just a purely documentary function, but real weight as objects – shown with their sometimes jagged-edged frames, precious artifacts as well as images. Many photos were in fact destroyed by Tayi in her attempt to erase images of her pre-revolutionary self, and one of the film’s most eloquent sequences shows Firouzeh’s childhood attempts to reconstruct the mutilated picture of her mother, drawing around surviving remaining scraps of picture. X-rays too play a key role, notably relating to a back injury incurred by Tayi in her youth, which – it’s indirectly suggested - may have had an influence on the direction her life would take.

Also running throughout the film is the leitmotif of a long white room, shown in slow tracking shots – representing the film-maker’s family home before her birth and during her childhood, its transformations reflecting those of Iran over the years. It is seemingly in the real-life original of that room that Khosrovani concludes the film,.

Khosrovani’s detached, forensic questioning of her family history may remind viewers of Sarah Polley’s similar investigation in Stories We Tell – albeit without the elaborate self-referential trickery – or the work of French writer Annie Ernaux. Her off-screen first-person narration is voiced throughout by the film’s editor Farahnaz Sharifi, while Soheila Golestani and Christophe Rezai provide the voices of the young Tayi and Hossein – the only real false note here, introducing a tone of somewhat stilted archness. Closing credits show Khosrovani herself, presumably, at work on a white background surrounded by a sea of photographs – a striking image, its power only somewhat undercut by the decision to give composer Peyman Yazdanian free rein with orchestrations of overbearing lushness. Otherwise, it’s the economy and reserve of Khosrovani’s approach that give the film such incisive and moving clarity.

Production companies: Antipode Films, Rainy Pictures, Dschoint Ventschr Filmproduktion, Storyline Studios

International sales: Taskovski Films, sales@ taskovskifilms.com

Producers: Fabien Greenberg, Bård Kjøge Rønning

Screenplay: Firouzeh Khosrovani

Cinematography: Mohammad Reza Jahanpanah

Editor: Farahnaz Sharifi

Production design: Iraj Raminfar

Music: Peyman Yazdanian

Featuring (voices): Soheila Golestani, Christophe Rezai, Farahnaz Sharifi

![The Brightest SunScreen[Courtesy HKIFF]](https://d1nslcd7m2225b.cloudfront.net/Pictures/274x183/3/5/0/1448350_thebrightestsunscreencourtesyhkiff_312678.jpg)

![The Brightest SunScreen[Courtesy HKIFF]](https://d1nslcd7m2225b.cloudfront.net/Pictures/100x67/3/5/0/1448350_thebrightestsunscreencourtesyhkiff_312678.jpg)