Clear-eyed portrait of Third Reich German filmmaker Leni Riefenstahl and her post-War attempts to rehabilitate her image

Dir/scr. Andres Veiel. Germany. 2024. 115mins

Those who hoped the art-versus-the-artist debate surrounding Leni Riefenstahl had died with the director will be appalled at the spectre Andres Veiel raises of Hitler’s friend, the Nazi-loving narcissist who made Triumph Of The Will and Olympia – and was once declared by Quentin Tarantino to be the best director who ever lived. She edged ever-closer to rehabilitation by the industry in her own 101-year lifetime, and there has been a sense of unease about that in the two decades since her death, for many reasons. With fresh access to her personal, self-serving and -aggrandising archives, Veiel lets Riefenstahl speak unedited: she puts a lot of issues to rest through her own lies, evasions and unrelentingly difficult personality.

Forensic and merciless

Much of Riefenstahl is already known to academics, although material from these archives has not been widely disseminated before. An intelligent film which isn’t particularly concerned with educating the uninitiated, it jumbles its timeline as it nips at Leni’s heels. Destined for festivals and art-house exposure for those fascinated by the knotty history of cinema and its relationship with politics, especially in Germany, Riefenstahl is forensic and merciless.

A new generation of cineastes may also be engaged by it: the film appears just as female directors make their mark in more than single figures. Leni Riefenstahl was one of the few, if not the only, female directors to become a household name, so dismissing her as a Nazi propagandist added an extra layer of complexity which she was more than happy to exploit. Riefenstahl shows that while she believed her own lies by the end, she still benefitted from too fast and easy a pass from those entranced by her aesthetics - aesthetics that don’t quite gel with society today. Hitler didn’t make her do anything.

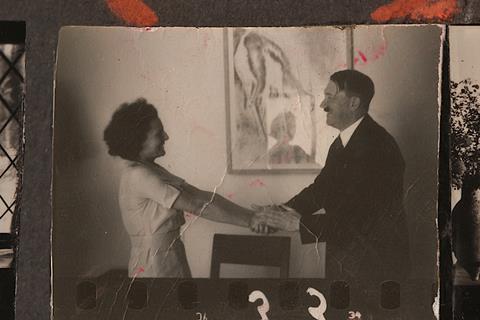

Veiel (If Not Us, Who?, Beuys) and journalist/producer Sandra Maischberger don’t particularly hail Riefenstahl’s achievements, although they catalogue the imagery, the iconography and the cinematic innovations still in use today. That’s not the point of Riefenstahl, yet Veiel’s hours in the editing suite watching her lie, dissemble and throw tantrums surely can’t have endeared him to her cause. They instead do a cool and efficient job of tracking this determined former dancer and actor through her life and career, especially her directorial debut, 1932’s drama The Blue Light, which Hitler so admired. The feeling was mutual: she wrote him a fan letter after watching him speak at a rally in 1932 which left her ‘overcome by a peculiar feeling’.

Where the film is most disturbing – and excels – is how it lattices her pre-war and wartime success (she never made another film after the conflict ended) into the lies she told to a nation and industry that almost preferred to be lied to. She needed more than to be acquitted of being a member of the Nazi party (which she never did join). She wanted full exoneration and acknowledged status as a genius. So she lied and bullied and evaded her way into the canon. She sued people who contradicted her. She worked as a photographer for The Times, no less. She went to Sudan and took photos of the Nuba tribe which were awfully reminiscent of her Nazi-era fetishization of bodily perfection.

Thus Riefenstahl also addresses a post-War Germany where the establishment carried on, with figures like the director and her friend Albert Speer able to benefit from a mix of Holocaust denial and uneasy self-justification. ”Should I have joined the resistance!?” Leni demands. Riefenstahl’s defiant defence of ignorance, the working-under-orders narrative, was common. She claimed, for example, not to have known about the fate of the Sinti children sprung from a death camp to appear in her film Lowlands. (They were murdered at Auschwitz.) She also denied witnessing a massacre of Jews in Poland as Hitler’s special correspondent, despite evidence to the contrary. In the face of what Veiel shows, the idea that Riefenstahl was simply ’unreliable’ is troubling. Then again, she was litigious. And she was talented.

Riefenstahl is a clean, precise piece of documentary film-making, which doesn’t sell itself out with arcs or underscore with music beats, opting for a still but haunting track by Freya Arne. There’s a sparingly-used voiceover narration which is a little jarring, but necessary as the film-maker deliberately skips chronology. The film doesn’t ask or answer the question of her genius, although reference is made to Willy Zielke, a producer she worked with, who filmed and edited the famous prologue for Olympia and was written out of it. And it won’t deter anyone from going back to acclaim her films, even if Leni Riefenstahl herself has fallen out of fashion and the ‘best of’ lists. It does, however, halt any attempt whatsoever at her personal rehabilitation.

It’s apt that Venice is hosting Riefenstahl. Olympia, her portrait of the 1936 Berlin Olympic Games in two parts, premiered on Hitler’s birthday at Riefenstahl’s own request and shared the top prize at Venice in 1938. Her bouquet was tied with a ribbon decorated in swastikas.

Production companies: Vincent Productions

International sales: Beta Films, beta@betacinema.com

Producer: Sandra Maischberger

Cinematography: Toby Cornish

Editing: Stephan Krumbiegel, Olaf Voigtländer, Alfredo Castro

Music: Freya Arde