TIFF opener is Hayao Miyazaki’s long awaited return to film-making

Dir/scr: Hayao Miyazaki. Japan. 2023. 124mins

For his first film in a decade, and most likely his last, writer-director Hayao Miyazaki revisits familiar themes — the fragile bonds of family, the delicate balance of the natural world — to tell an achingly beautiful story about a 11-year-old boy in mourning for his dead mother who may not really be gone. The Boy And The Heron marks the return of the animation auteur, who announced his retirement after his Oscar-nominated 2013 picture The Wind Rises, delivering a film full of stunning images that vary from sublime to nightmarish. Drawing from elements of his own childhood, Miyazaki has dreamed up a fantastical environment in which anything seems possible — including the potential to remake oneself.

A film full of stunning images that vary from sublime to nightmarish

Opening in Japan in July without advertising or trailers, The Boy And The Heron was an event in Miyazaki’s home country, scoring the director’s biggest ever opening, and a similar buzz should greet the animation when it premieres as Toronto’s opening night film. (The picture then makes its way to the New York and San Sebastian festivals, and has sold to multiple territories including Gkids for North America.) At 82, Miyazaki is among the most revered living filmmakers, and his fans will no doubt be ecstatic to see another picture from him. Awards recognition is likely as well.

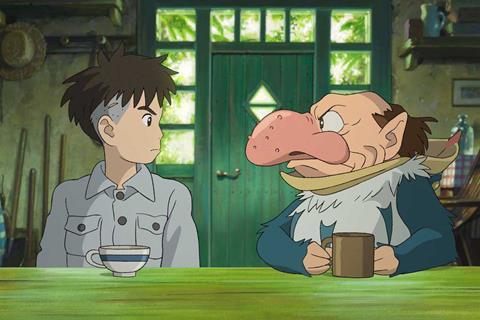

In the midst of World War II, young Mahito (voiced by Soma Santoki) has fled from Tokyo to the countryside with with his father Shoichi (Takuya Kimura). The boy is still shattered by the death of his mother Hisako, who perished in a fire. Shoichi, however, has moved on with his life, marrying Natsuko (Yoshino Kimura), Hisako’s younger sister, with a baby on the way. Mahito is having trouble adjusting to this new arrangement — he gets uncomfortable when locals mention how much Natsuko looks like the late Hisako — and hints of his mental distress show themselves when one day he hits himself in the head with a rock. But soon, Mahito meets a bizarre talking Grey Heron, which actually has a man inside it (Masaki Suda) claiming that the boy’s mother is not really dead.

Working with longtime producer Toshio Suzuki and his regular composer Joe Hisaishi, Miyazaki effortlessly steps back into his distinctive style, which combines impish humour with serious themes, the animation highly naturalistic until the characters venture off into parallel realms, where astonishing visuals take centre stage. (“A lot’s strange about this place,” a character notes early in The Boy And The Heron, a declaration that will be warmly received by the filmmaker’s adoring throngs who savour his trips into the surreal.)

When the Grey Heron guides Mahito through a land in which the living and the dead intermingle, the boy will discover, among other things, where babies really come from, with Miyazaki introducing us to the Warawara, impossibly adorable little critters who look like balloons with feet, hands and happy smiles. Not unlike Spirited Away, The Boy And The Heron is the saga of an impressionable child on a magical odyssey, and Miyazaki (with assistance from art director Yoji Takeshige) dots Mahito’s journey with one striking locale after another. Every time the film presents us with a cute or tranquil moment, the story quickly shifts gears, demonstrating that the most unexpected terrors also exist in this parallel realm — whether it’s carnivorous pelicans or fearsome parakeets. Even the Grey Heron is a disturbing sight, the man’s large mouth and menacing teeth jutting out from the bird’s beak.

None of these arresting visuals would matter, however, if not for the strong emotional undercurrent Miyazaki brings to the proceedings. Hisaishi’s piano-centric score is a stark wonder, highlighting Mahito’s endless longing for his beloved mother as the boy searches for clues to her whereabouts (in the process learning much about his ancestors’ surprising connection to the planet). Often in his work, Miyazaki has lamented the imbalance between humanity and nature, but his latest film feels especially fraught in this regard. Between the carnage of World War II and the feuding factions within this parallel realm, The Boy And The Heron views society with a fair share of pessimism, holding out hope that individuals and families can help heal those deep wounds. That the filmmaker manages to blend this universal plea with an intimate tale of a boy making peace with his personal tragedies is even more impressive.

Perhaps The Boy And The Heron does not quite reach the heights of Miyazaki’s greatest achievements. The storytelling can sometimes be cluttered, and the narrative momentum occasionally stalls before a moving third act. But those reservations are minor when considering this lovely valedictory statement from a humanist filmmaker long invested in how people treat one another — and the magical creatures that periodically intervene to help them change their ways. This is not the first time Miyazaki has claimed that he has made his final film but, if it is, it is a wholly satisfying, bittersweet sendoff.

Production company: Studio Ghibli

International sales: Goodfellas sales@goodfellas.film

Producer: Toshio Suzuki

Editing: Takeshi Seyama, Rie Matsubara, Akane Shiraishi

Music: Joe Hisaishi

Main voice cast: Soma Santoki, Masaki Suda, Ko Shibasaki, Aimyon, Yoshino Kimura, Takuya Kimura