An ‘intractably hardcore’ work by Jean-Luc Godard.

Dir: Jean-Luc Godard. Switzerland/France. 2018. 85 mins.

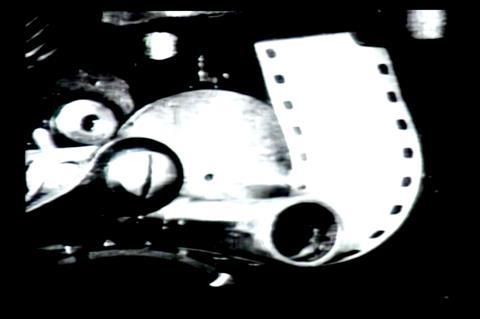

A new work by Jean-Luc Godard is always an event – if not in the outside world, then certainly in the context of Cannes, where it briefly attains public prominence before being handed over to be sifted for clues by armies of academics and exegetes. You could almost say that a Competition premiere of a Godard work in the Grand Théâtre Lumière is less a cinema screening in the normal sense than a one-off site-specific art installation. This is definitely the case with The Image Book, a meditation in sight, sound, text and blazing colour that is intractably hardcore even by the standards of his recent work like Film Socialisme and 3D experiment Farewell to Language.

The Image Book if nothing else, is inestimable, in that it defies normal estimation or assessment;

A Godard work this tough faces the viewer with a singular challenge: shrug and assume, as so many have in the past, that the director has lost the thread (as if he were ever interested in anything so linear as a thread) or take a bet that there is a hidden logic in the work and submit oneself (critically, of course) to that logic.

The Image Book – which dispenses with narrative and actors, but uses a number of recorded voices, including the director’s - is unmistakeably a one-man production in the manner of his epic 1988 video cogitation Histoire(s) du Cinéma. But it is also credited – on the press book and in barely readable scrawled on-screen captions - as a collaborative venture with Swiss film-maker Fabrice Aragno, former Godard production manager Jean-Paul Battagia and academic and theorist Nicole Brenez. Press material credits them with ‘montage’ – which no doubt means not strictly editing but a collaborative montage of ideas, presumably developed during long, dense discussion.

Like recent Godard works, The Image Book is divided into several chapters, and like Histoire(s) du Cinéma, of which it resembles a hyper-charged, more aggressively fractured sequel, it mobilises a sometimes barely readable flash storm of spoken and on-screen texts, film and TV clips, artworks, etc to create the impression of a suggestive discourse about the contemporary condition – although the meaning of that discourse is to be read strictly between the lines and the images.

Certain strands of themes emerge fairly clearly, beginning with a succession of images of hands and fingers, illustrating (or illustrated by) the spoken statement that “man’s true condition is to think with hands” (we never know the exact source of the film’s texts, but the film helpfully includes a list of sampled references at the end, for those rapid enough to scan them). Another suite of images concerns trains, indissolubly linked – in Godard’s work and in the modern consciousness – with the Holocaust, and characteristically for him, Holocaust images appear, alongside extracts of films related to World War Two (among them, Jacques Tourneur’s Berlin Express).

A later theme concerns the Middle East, and the Western incapacity to understand it as anything but an indefinable ‘other’: this comes under the chapter heading ‘Joyful Arabia’, the title of a work by Alexandre Dumas. This long, sustained section, which therefore comes across as the most clearly coherent in the film, mixes images from the cinema of the Arab world with TV news coverage (Isis-related images occur throughout The Image Book) and video (possibly iPhone) images of the Middle East that seem to be the only expressly shot material in the film. Fragments of a narrative recited through this section, involving a sheikh’s aspiration to rule the entire Gulf, are taken from a 1984 French novel by Albert Cossery, Ambition in the Desert.

Only the most naïve would dare recap with the question “What does it all mean?” – since a simple answer is surely beyond reach, and since the real question with Godard is always, “How does it all mean?”. The Image Book pushes Godard’s sampling method to the extreme, with its aesthetic of absolute fragmentation and frustration. Frustration, that is, because his method of cutting off and distorting voices, and of whisking complex texts away before hitting us with further wave upon wave of image and language, makes clear meaning almost impossible to latch on to – like speeded-up atonal music which it’s barely possible to glean for structure, let alone melody. For the record, this soundtrack contains, among more accessible classical composers, noted sonic radicals such as Alfred Schnittke and Scott Walker.

Among untreated film clips, including many from his own work, Godard again offers violently hued, distorted images, some so texturally distressed that they resemble Robert Rauschenberg screen prints. Meanwhile, Godard himself can be heard intoning – and towards the end, coughing - balefully among the voices, which bounce and distort in a complex sound mix, testing our comprehension. Many will hear his tones as embodying an inscrutable, gnomic, ineffable wisdom; for many others, watching and listening to The Image Book will chime with a phrase heard here: “Chatting with a madman is an inestimable privilege.” The Image Book if nothing else, is inestimable, in that it defies normal estimation or assessment; to encounter a film this intransigently confrontational by an artist who shows no sign of softening will be a nightmare for many, but yes, for many a privilege and a pleasure.

Production companies: Casa Azul Films, Ecran Noir Productions

International sales: Wild Bunch, edevos@wildbunch.eu

Editors: Jean-Luc Godard, Fabrice Aragno, Jean-Paul Battagia, Nicole Brenez

![The Brightest SunScreen[Courtesy HKIFF]](https://d1nslcd7m2225b.cloudfront.net/Pictures/274x183/3/5/0/1448350_thebrightestsunscreencourtesyhkiff_312678.jpg)

![The Brightest SunScreen[Courtesy HKIFF]](https://d1nslcd7m2225b.cloudfront.net/Pictures/100x67/3/5/0/1448350_thebrightestsunscreencourtesyhkiff_312678.jpg)