Are the numbers beginning to add up for video-on-demand? Robert Marich takes a look at the figures being generated in the US market, which is acting as a testing ground for global VoD patterns

Video-on-demand revenue for films is finally growing from a trickle to a meaningful revenue stream that is mostly benefitting major studio films.

“On a really big film, the domestic VoD number is up to $10m or even more in revenue to the studios,” says Stephen Einhorn, New York-based media consultant and ex-president of New Line Home Entertainment. “So it’s gotten big enough to get the attention of studio executives. But it doesn’t change whether a film will be greenlighted or not, or alter the decision whether or not to acquire an independent film.”

London-based analyst Screen Digest estimates global VoD consumer spending to have reached $2.9bn in 2009, and forecasts it will hit $5.3bn by 2012. Until now, VoD has disappointed because of its slow growth, while being blamed for inflicting even larger disruption on the more lucrative physical DVD business.

“VoD has gotten big enough to get the attention of studio executives. But it doesn’t change whether a film will be greelighted or not.”

Stephen Einhorn, New Line Home Entertainment

The global VoD movie consumer level spend of $2.9bn in 2009 is about 19% of the physical DVD market. The 2012 $5.3bn figure could be approximately 58% of the DVD market, as VoD grows and DVDs decline.

Why the surge now? Consumers are able to view VoD on more than just computer screens. Video-game consoles, TV sets with built-in web-connections, Apple’s new iPad tablet and mobile phones comprise a new wave of VoD platforms, augmenting subscription cable/satellite TV, Apple’s iTunes handhelds and websites.

Sony’s Bravia television sets present a case in point of technology evolution as catalyst for growth. Sony recently offered a free 24-hour rental of Sony Pictures animation Cloudy With A Chance Of Meatballs (pictured) in a promotion for US buyers of its Bravia TV sets and Blu-ray DVD players. These now have built-in web connections that facilitate seamless VoD. Back in 2008, when Sony offered a video stream of Hancock to US consumers, it required the purchase of a $300 peripheral device to connect Bravia TV sets to the web.

US testing ground

At present, the US accounts for half of global VoD revenue for films, while the next largest territory — the UK — represents just 6%. So the sprawling and diverse US is the trend setter.

Universal Pictures is testing US consumer response to an early VoD rental window for its comedy The Boat That Rocked (aka Pirate Radio). The film will be available from March 11 via VoD, a month before the physical DVD release on April 13. Ordinarily, VoD is simultaneous with or follows the DVD window. Universal believes The Boat That Rocked, which grossed a modest $8m theatrically via Focus Features, is most suited for rentals (VoD in other words) while DVD is more of a sell-through window.

The majors remain cautious and inclined to test rather than plunge, after being burned by their costly Movielink debacle. But the majors are exploiting the smallish VoD window in hotels, for example. Hotel VoD marketer LodgeNet Interactive says 41 of its mainstream theatrical films generated more than $1m each in VoD revenue in the US in 2009 (see charts, attached or below).

The price of VoD

VoD takes several forms: single view or permanent ownership via paid-for electronic sell-through; subscription VoD offering a pool of content for unlimited viewing for a flat fee (popular in cable TV); and free viewing with advertising for older movies. At present, US distributors generally receive a larger slice of consumer spend for VoD — around 70% — than other windows, such as the 50% for cinema tickets.

But VoD is expected to be less lucrative than the DVD window it is squeezing. Although the hope is the sizeable $3.99 VoD price level popular in cable will stick, the 99-cent a day DVD kiosk is creating downward pressure in the US.

“The key to growing the market is finding the right price point,” says Rob Aft, president of media finance adviser Compliance Consulting in Los Angeles. “At what price are young people willing to pay rather than pirate? Is it a dollar or two dollars? The industry needs to experiment to find out.”

Field trials by cable and satellite platforms are under way in the US which allow subscribers to watch programmes on-demand on multiple devices — also helping to keep VoD prices down. The pay-TV operators hope cross-platform on-demand will increase customer satisfaction and reduce disconnects. A further cross-device effort involves cloud computing, where content is stored remotely and can be accessed on multiple devices.

Long tail shrinks for indie film

While big films are achieving sizeable sales in VoD, indie titles seem to be left behind. This seems counter-intuitive: VoD is supposed to make the so-called ‘long-tail theory’ a reality by making less well-known content easy to locate and access, driving up sales. After all, VoD platforms can stock more titles than bricks-and-mortar video stores and there are no physical DVDs to replicate.

“The problem is that we’re losing the middle man that serves an important marketing function,” says Meyer Shwarzstein, head of indie film aggregator Brainstorm Media in Los Angeles. “When you walk down the aisle of a video store, the store does some of the marketing by exposing consumers to titles. It’s a form of browsing.”

The decline of video stores puts more marketing responsibility on the shoulders of film distributors, Shwarzstein adds.

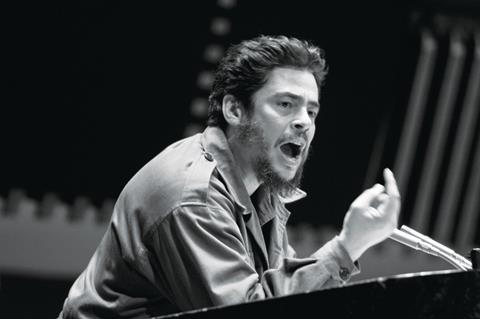

Some indie films achieve decent VoD business in the US. Orchestrating a simultaneous theatrical/VoD release, IFC Films generated more than $1m in VoD revenue for Steven Soderbergh’s Che (pictured), more than $500,000 for Italian mafia drama Gomorrah, and around $500,000 for political comedy In The Loop, according to industry estimates. These figures are pumped up by an average VoD consumer price of $7.

“The video store does some of the market by exposing conusmers to titles. It’s a form of browsing.”

Meyer Shwarzstein, Brainstorm Media

However, the reality is that big aggregators such as iTunes simply focus on the major films.

In a conference call with investors in January, Netflix CEO Reed Hastings told them he was not interested in swelling Netflix’s movie count for its Watch Instantly web-streaming service. “You can imagine we could quickly license, if we wanted, 100,000 irrelevant titles,” said Hastings, whose company is a major buyer of films. “If we had 1,000 of the biggest titles, that would make a much bigger difference than 10,000 others.”

Still, VoD provides some revenue gain to small films. Genre-focused VoD and streaming websites such as FearNet will license non-theatrical films, but at rates as low as less than $10,000 for windows stretching six months or more. The only good news for film-makers and distributors is that such low-revenue deals tend to be non-exclusive, allowing the film to be licensed elsewhere at the same time.

Other websites make no minimum guarantee to film distributors but simply offer revenue sharing with an uncertain payout, which can be miniscule.

The precarious state of independent films in VoD is demonstrated by the early response to YouTube offering $3.99 VoD play of Sundance movies The Cove, One Too Many Mornings, Homewrecker, Children Of Invention and Bass Ackwards (pictured). According to a report by The New York Times, the five had 2,684 views in their first 10 days, generating just $10,709.16 in revenue, despite festival publicity and promotion on YouTube.

Click here for a breakdown of the video-on-demand market in the US for 2009.

1 Readers' comment