Dir: Jean-Pierre Ameris. France. 2012. 95mins

Victor Hugo’s rambling The Man Who Laughs (L’homme qui rit) has already engendered one filmed masterpiece, Paul Leni’s silent classic by the same name, which put the deformed face of Conrad Veidt in every self-respecting cinema manual around the world. More film and TV adaptations have followed but none particularly significant, and it looks like Jean-Pierre Ameris’ new attempt to deal with Hugo’s prose will join that list.

Gwynplaine’s make-up, a crucial factor in this case, is far too bland, neither grotesque nor outlandish enough to generate mirth or horror and never looks more than just what it is, a painted face.

An uninspired condensation of a vast and tortuous novel, shot almost entirely inside Prague’s Barrandov Studio and lifting the story completely out of its time and place context - that is England in the late 17th century - Ameris’ version not only takes numerous shortcuts through the plot, preferring to stress the political subtext running through it, but also tries to turn it into a timeless metaphor, valid at all times for all places.

Hugo’s tragic tale starts with a disfigured boy, Gwynplaine and the blind baby girl, Dea, he saves from death, growing up under the protection of a travelling mountebank, Ursus, and sharing his caravan as he goes from one country fair to another. For 15 years they live happily together, the horrid smile carved on the boy’s face becoming the feature that gains their shows a reputation around the fairgrounds.

That is, until it turns out Gwynplaine is the heir to a great fortune and title, which are restored to him with all due pomp and circumstance. Once he tastes the dubious delights his new position offers, he prefers to give it all up and return to his beloved Ursus and Dea. But when he does it is already too late. She dies in his arms and he commits suicide, leaving a desolate Ursus to mourn them both.

Creating a completely fictive reality unconnected to any substantial historical references is a pretty high order to fill, too much for the production design that fails to come up with solutions that will look more than studio sets. The predominantly dark images may be justified at times by the plot itself, but audiences will find themselves quite often wondering whether a scene takes place in the morning, noon or at night.

Gwynplaine’s make-up, a crucial factor in this case, is far too bland, neither grotesque nor outlandish enough to generate mirth or horror and never looks more than just what it is, a painted face.

Gerard Depardieu a natural typecast for the role of the corpulent Ursus has no problem with the homespun character he has to put forward, but Marc-Andre Grodin (who plays Gwynplaine) seems rather lost when he makes such statements as “the misery of the poor makes the paradise of the rich”.

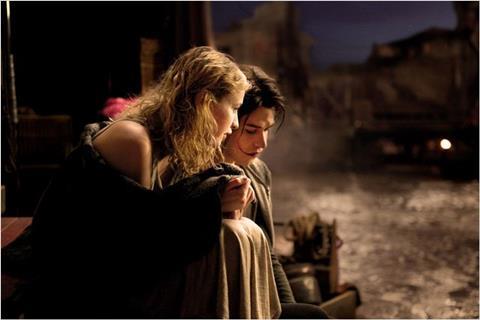

His scenes with Christa Theret (Dea) at the fairs justify none of the emotions their audience in the film pretends to experience and the “eternal smile” on his handsome face doesn’t really change it that much. The classic silent, when released again a few years ago, was described in some reviews as a blend between horror and swashbuckling. Film critics will have a field day tackling this one.

Production company/sales: EuropaCorp, www.europacorp.com

Producers: Edouard de Vesinne, Thomas Anagyros

Screenplay: Jean-Pierre Ameris, Guillaume Laurent, based on Victor Hugo’s novel

Cinematography: Gerard Simon

Editor: Philippe Bourgueil

Production designer: Franck Schwarz

Music: Stephane Mucha

Main cast: Gerard Depardieu, Marc-Andre Grodin, Chrsta Theret, Emmannuelle Seigner