Double Oscar winner Alexandre Desplat scores his fifth feature for Wes Anderson with The French Dispatch. Screen talks to the composer about a career spanning more than three decades.

You might expect music by a Paris-born composer for a film called The French Dispatch to sound distinctly French. But rather than an obvious Gallic flavour, Alexandre Desplat’s score for Wes Anderson’s latest wryly eccentric comedy drama — the fifth feature collaboration to date between the composer and the writer/director — has, to Desplat’s ears, a “more American, jazzy/bluesy” feel.

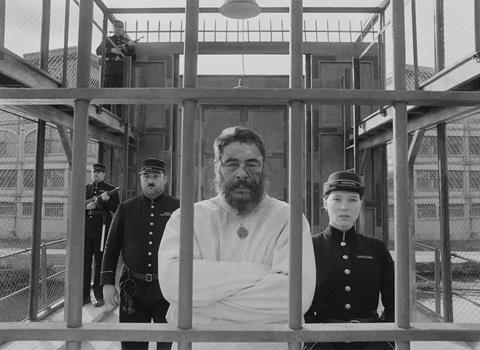

The score is just one of the unexpected elements of the film, an anthology of four unlikely stories from a fictional American magazine covering a poetic, bygone version of France. The ensemble cast includes Owen Wilson as a cycling reporter, Benicio del Toro as a criminally insane painter, Timothée Chalamet as a radical student and Edward Norton as a kidnapping chauffeur.

Following their usual practice, the composer and director talked early on about musical ideas for The French Dispatch, and Desplat was reminded of the work of the absurdist artists who launched an early 20th-century Paris-based art movement. At the core of the film, the composer felt, was “something very Dadaist, completely lacking in logic. I love the Dadaist movement’s rejection of logic and use of humour to build a work of art. So we tried to play with logic — or illogic — in the music too.”

As Anderson and Desplat continued to exchange filmed sequences and musical sketches, another goal for the score emerged. “Because the movie is so virtuosic, with such a flow of ideas,” Desplat explains, “the music also had to be sparse and minimal, to leave room for what’s on screen. It’s the opposite of what you would think — that the score should be big and active, mirroring what’s on screen.”

The result was a score that begins with solo piano music, played on the soundtrack by renowned classical pianist Jean-Yves Thibaudet, and gradually adds instruments including harpsichord, bassoon, tuba, percussion and banjo — an Anderson favourite — into the mix as the film’s four narratives successively unfold. (The soundtrack also includes a song performed by former Britpop star Jarvis Cocker, who has released Chansons d’Ennui Tip-Top, a companion album to the film with covers of vintage French pop numbers.)

In the cavernous prison setting of del Toro’s episode, for example, “We wanted the silence to be present and only a solo piano would help us to do that,” says Desplat. In later episodes, “the piano was the bones and we added flesh, made of many different instrumental colours, around it. And then there are recurring motifs that we hear throughout the film but played by different instruments, to establish a kind of continuity.”

Historical notes

Desplat’s working relationship with Anderson dates back to 2009’s Fantastic Mr Fox and, with 2014’s The Grand Budapest Hotel, brought the composer one of his two original score Oscars, as well as one of his three Baftas.

Composer and director have developed a process that begins with Desplat offering musical ideas for the project that Anderson has just finished shooting. “It could be 10, 20, 30 motifs or instrumental colours,” says the composer, “and then he picks and chooses and I reorganise the elements and they become the score.”

The relationship has lasted, Desplat suggests, because “we respect each other. And there’s something very childlike about Wes. It’s like when you were a child and your best friend came to your house and you closed your bedroom door to play with all your toys. The fantasy world of childhood comes back and you can try anything. There’s a sense of poetry and a freedom in his films, though he hides it behind all the virtuosity.”

Anderson is by no means the only filmmaker to seek out the prolific Desplat — who was raised in France by a French father and a Greek mother and still lives in Paris — as a regular musical collaborator. Over the course of a 36-year career in the European and US industries, Desplat has scored seven films for Jacques Audiard, winning best score Césars for the director’s Rust And Bone and The Beat That My Heart Skipped; six for Stephen Frears, including The Queen and Philomena; and seven, among them Argo and The Monuments Men, for (as either producer or director) George Clooney.

Each ongoing collaboration has its own process, Desplat explains. “These directors are human beings,” he says. “You can’t have the same relationship with Jacques Audiard and Stephen Frears and Kathryn Bigelow [on Zero Dark Thirty] and Nora Ephron [on Julie & Julia] and Wes, because they’re different personalities. You have to approach each relationship in a different way, and each time it’s a new adventure. Sometimes even with the same director it’s a new adventure.”

Desplat’s latest exploits have seen him reunite with three familiar, but very different directors. Some musical pieces have already been written for Anderson’s romance Asteroid City, currently being edited after its shoot near Madrid. Now Desplat is waiting to see a cut of the film before putting those pieces and fresh material together in a score.

Pinocchio, a stop-motion animation take on the classic tale from Guillermo del Toro (for whose The Shape Of Water Desplat won his other Oscar) should also be ready soon for its full musical accompaniment. Desplat, who wrote a few hit numbers when he was a young composer working in France, has already written and recorded some songs for the project.

Frears’ The Lost King, a drama starring Sally Hawkins about the search for the remains of England’s Richard III, had its score recorded with Desplat leading the London sessions. “It was a beautiful experience to be with musicians in the studio again, and with the director, not just by Zoom,” the composer enthuses.

Maintaining the pace

With close to 200 feature credits, more than 40 television projects and 11 Oscar nominations under his musical belt, Desplat has no plans to lighten his workload, either in the US or Europe (where his recent French projects have included Martin Bourboulon’s drama Eiffel and Guillaume Canet’s thriller Lui).

“I love to work a lot, and to work fast,” he says, suggesting it is the nature of the collaboration that is more important than whether the work is on studio or independent projects in the US, or more modest productions in Europe.

“I’ve been very lucky to work with directors who have the same passion for cinema that I have,” Desplat continues. “I never had to fight against my taste or my will. The scope is sometimes smaller [on European projects], so I’ve learnt through the years to work with smaller ensembles. But aside from that, the relationship with the director is the same — it’s creative.”

The musical purpose is the same too, he adds. “I try to bring something to the film that it doesn’t have — an extra vibration, an extra sensitivity. Something that’s there but that one cannot yet see or feel. That’s why I work so hard, I guess, because I want to find that gem which is hidden in the film and bring it to the light

No comments yet