Barry Levinson, director of Monday’s Toronto world premiere The Survivor, has never forgotten the strange man who shared his childhood bedroom in Baltimore for a brief spell in 1948 and tossed and turned and moaned in his sleep.

“It was my grandmother’s brother, who I’d never heard about. He stayed with us for two weeks,” says the director, who was around five at the time. “He was going on in a language I didn’t understand… Almost every night I’d wake up to something happening. I didn’t understand.”

That man was his great uncle Simcha and it was only some years later when his mother told him he was a concentration camp survivor that it all made sense. So Levinson had to say yes when he read Justine Juel Gillmer’s screenplay about the life of Harry Haft based on the book by Haft’s son Alan Scott Haft.

Haft grew up in Poland and was deported to Auschwitz as a young man in 1942. He stayed alive by winning more than 70 deadly bare-knuckle bouts against fellow inmates for the entertainment of the Nazi guards. The loser was shot on the spot or sent to the gas chambers. He eventually escaped and made his way to New York where he boxed for several years and landed a fight with legendary Rocky Marciano in the hopes that the publicity would reunite him with his lost love.

“One of the main aspects of it that affected me was the idea of post-traumatic stress disorder,” says Levinson. “Yes that chapter [in the camps] ended, but the emotional horrors – how do you come to terms with it and how do you get on with your life after you survived?”

Casting Ben Foster

Levinson and the producers reached out to Ben Foster, whose work in films like Leave No Trace, Hell Or High Water and The Messenger had won admirers in Hollywood but never quite leading man status. He had also acted for Levinson some two decades prior in Liberty Heights. “He’s a great character actor; he becomes other people,” says Levinson, whose credits include Good Morning Vietnam, Rain Man and Diner.

Foster’s grandparents had escaped the pogroms in the Ukraine and arrived in Ellis Island in the 1920s. He read the script that day and called back. “He gave me my first real job when I was 17, Barry shaped me very young and I’ve carried Barry with me in terms of approach,” say the actor. “Barry’s bullshit meter is very high and if it doesn’t feel right, in the moment, he’s going to go after it and explore it.”

To portray Haft, who died in 2007, Foster worked with dialect coach Erik Singer and Yiddish expert David Braun to nail the accent from Haft’s birthplace in Bełchatow, Poland. “We do have tapes of Harry but it didn’t feel like it should be mimicking,” says Levinson. “We wanted to ground the sound [of Haft’s voice] in that time, that place, and then evolve it through the three decades of Harry’s life as he becomes more Americanised and ages.”

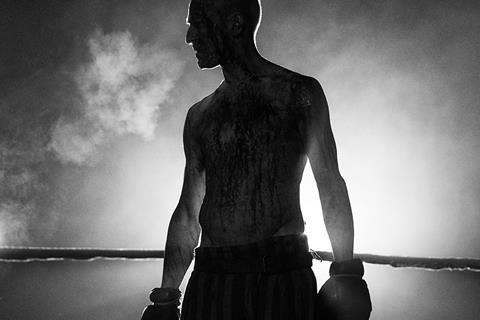

Foster went on a severe diet and lost 62 pounds for the concentration camp scenes, which are shot in black and white and restrict the depiction of Auschwitz mostly to Haft’s personal nightmare: violent fights at the behest of Schneider (Billy Magnussen), an SS officer who accepts the horrors around them with chilling indifference and makes a tidy profit from his prisoner’s prize firsts.

He worked with make-up artist Jamie Kelman, whose expertise with prosthetics and make-up rendered Foster in the wartime and post-war scenes almost unrecognisable. For the weight fluctuations, Foster was determined to do it the old-fashioned way. “I needed to feel it in my body,” the actor says. “I needed to feel that hunger to inform the rest of his life in the film.”

Foster worked with boxing trainers and regained 54 pounds for the Marciano sequence: “I ate lots of pasta. Loved that part.”

Visiting the past

The US-Canada-Hungary feature from Bron Studios and New Mandate Films shot chronologically. Principal photography in 2019 lasted 34 days, starting in Budapest’s Fot Studios in Hungary where production designer Miljen Kljakovic recreated parts of the Jaworzno work camp outside Auschwitz, before relocating to New York and finally a few days in the Deep South. Filming had wrapped when Endeavor Content launched sales at Cannes Marché that year and brought Levinson and Foster with a teaser. The pandemic delayed plans to premiere the film until now.

Levinson and Foster visited Auschwitz before the cameras rolled. As the actor recalls, “It’s very different than reading about it or hearing about it; to touch the brick, to touch the iron, to see the shoes with your own eyes. You start building an internal world that has a bit more of a tactile inner life. I plastered my home and my trailer with photographs of the atrocities. They built a 360-degree set so when I dropped away it was very easy to fall into this hell because the pictures were everywhere.”

There are no grandstanding speeches and the familiar visual grammar depicting Nazi atrocities is largely absent. With Foster it is mostly in the eyes, the intonation in his voice and the way he carries himself, both during the Holocaust sequences and the post-war scenes that make up most of The Survivor’s run time of two hours and nine minutes, when Haft wrestles with survivor’s guilt and gets to know a woman (Vicky Krieps) who helps survivors relocate their loved ones.

“This is a man who is basically living with a past that he can’t let go of but he can’t articulate it – it comes out in bits and pieces and I believe that pulls us in, because we’re not getting all the information with such perfect clarity,” says Levinson. “And by doing so you infuse the characters with a certain kind of humanity.”

Haft’s story resonates with present-day intolerance and the crisis of displaced people. “I find it a humanistic piece,” says the director. “You survive but then you have to find a way to live, to put the demons to rest and ultimately relax into life. When you see the Vietnam vets that came back it wasn’t like the war was over; some of them grappled with those issues, those fears, those nightmares that don’t go away that easily.

“That was the first thing that I connected to, because of my great uncle; that that you carry the damage and it affects us in ways that we can’t quite explain, that affect our behaviour. And so finally [Haft] was able to come to rest. And at the same time there’s a love story that runs through [the film]. He basically survives because of this love, the infatuation of a young girl that he met.”

Foster adds, “Being a refugee is an old tale and a relevant one. So we’re in service of empathy, that’s our job. Hopefully, this film can be a signal that isn’t so much a time capsule as far as a reminder that while we can’t know what you’ve gone through, we can’t know exactly where you’re coming from, we can meet you today in order to meet a better tomorrow.”

The Survivor from Bron and New Mandate Films premiered on Monday (September 13). Endeavor Content represents worldwide rights.

![The Brightest SunScreen[Courtesy HKIFF]](https://d1nslcd7m2225b.cloudfront.net/Pictures/274x183/3/5/0/1448350_thebrightestsunscreencourtesyhkiff_312678.jpg)

No comments yet