Squid Game production designer Chae Kyoung-sun, editor Nam Na-young and cinematographer Lee Hyung-deok tell Screen about their roles on the Netflix sensation.

Hwang Dong-hyuk, the director and creator of Korean drama sensation Squid Game, wanted to create spaces and visuals that had never been seen before in his home country. He and his team delivered on his lofty creative ambitions, drawing in not only millions of Koreans but mesmerising audiences around the world. The show landed Netflix its biggest global hit, drawing 142 million subscriber households in its first month of streaming in 2021 and ranking number one in 94 countries, including the UK and the US.

Hwang initially touted Squid Game in 2009 but had to wait nearly 10 years until Netflix’s interest was piqued as part of its commitment to grow its international programming.

The show revolves around a fictional contest in which 456 players, most of whom are in deep financial trouble, risk their lives to play a series of deadly children’s games for the chance to secure a multi-billion won cash prize, with many dying during the process. It deals with economic strife, class disparity in Korea and capitalism, all through a uniquely Korean lens.

Production designer Chae Kyoung-sun says that when Hwang asked her to join the team, he promised the show would give her opportunities to try something new.

“Production design in Korea is mostly centred on recreating existing spaces, but Hwang wanted to create spaces and visuals never-before-seen in Korean shows,” says Chae.

Editor Nam Na-young says Hwang wanted all 456 of the game’s participants to be main characters. “He wanted to show how each contestant who survived each stage changed, and what kind of facial expressions they made, so this is the part that I focused mostly on,” says Nam.

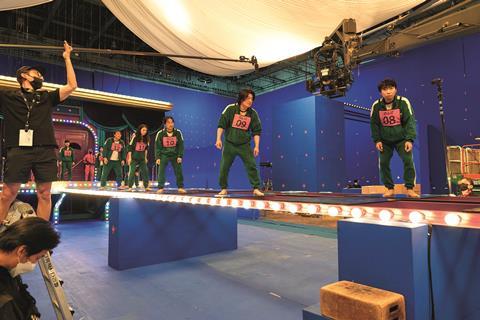

Long shots of the contestants entering the games were used to ensure all were visible. “I refrained from using too many techniques when showing the background story of each of the characters,” explains Nam. “I just tried to show their story as is.”

Capturing the contestants’ dejection and desperation in the outside world was key for cinematographer Lee Hyung-deok. “Colours in low saturation, lighting in low contrast and creating the dull and grainy look and feel of a film camera — even though I was using a digital one — were some of the elements I had in mind,” he says.

The game appears to be a fantasy as the characters start to play. But then the horror reveals itself, calling for a change in approach. “I used highly saturated colours with strong contrast in light [for the game sequences],” Lee says. “I wanted to bring to the screen the wide spectrum of emotions of the characters and their changes through the betrayal and trickery in the most desperate moment of survival, the rage and violence, and the selfishness and altruism.”

Real-life inspiration

As the competition is based on children’s games that were played in Korea during the 1970s and ’80s, the show heavily references that era: the giant doll robot Younghee was inspired by illustrations in elementary school textbooks; the alleyways in which the contestants play marbles resemble common Korean neighbourhoods of the time. Early on, Hwang told Chae he was determined the show would feature one of his vivid childhood memories — of a sunset falling on the alleyways where he played as a youngster.

Another image that first came to mind when reading the script became Chae’s primary concept for the art design — a broken ladder leaning against high walls that surround a man on the ground, with him glancing helplessly at the damaged equipment.

“The illustration had a fairy tale-like feel to it but was also sad — the man being shut out of society and the competition therein seemed disturbing,” says Chae. “I thought it fitted well with the uniquely Korean fairy tale-slash-fantasy that Hwang had in his head. Visually, we wanted to divert from the typical genre element of survival games and death games.”

This mix of otherworldly horror, primary colour set designs and the contrast in worlds marks the show out as different and underlines its Korean essence.

Squid Game landed amid a time of international audience appetite for Korean content; think of the current success of Korean television formats such as The Masked Singer and The Masked Dancer, and the Oscar success of feature Parasite, directed by Bong Joon Ho and co-written by Han Jin-won. It is telling that Squid Game streamed to global audiences with no cuts, changes or tweaks.

“Experiencing foreign languages and culture have become much more commonplace,” notes Chae. “Working on Squid Game, I wasn’t mindful of the cultural elements of different countries. I simply wanted to create a space for the characters written in the script.”

Set challenges

Squid Game filmed over seven months in Korea’s fifth-largest city Daejeon (where parts of 2016 horror hit Train To Busan were shot) and the directing and production departments tried out everything themselves, from the squid game to the glass stepping stones and tug of war.

The structure of the set was the first of its kind, which meant Lee and Chae spent hours working things through. “We rented three to four large studios to build our own sets, one to two months prior to the shoot,” says Chae. “While finished sets were used for filming, we kept building other sets next to them. We planned everything out to maximise efficiency, and ran simulations for all the games.”

For Nam, it was a new experience taking on a series, as her previous work had been in features.

“The challenge was that I had to consider not only the editing in a single episode, but also to make sure it flowed organically with the overall series,” says Nam. She allotted 10 days of editing for each episode and meticulously planned the work before starting.

Cinematographer Lee also came from the world of film. “Shooting something that is as long as Squid Game within a limited span of time effectively was a challenge,” he says. “Changes in the filming schedule due to Covid-19 also disrupted the flow but the filming schedule was, overall, quite reasonable.”

The show’s critical and commercial global success, and its presence in awards chatter, are testament to the collaborative effort it took to make it. Chae credits the countless meetings that she and Lee had before the shoot with achieving the visual and emotional balance of the show.

“I wanted to understand and relate to these characters, and my hope was that this would translate into the production design,” she notes. “This show made me realise that when you fully understand the characters and feel affection for them, you can invite everyone to resonate with it, and go beyond the message that the show tries to deliver.”

![The Brightest SunScreen[Courtesy HKIFF]](https://d1nslcd7m2225b.cloudfront.net/Pictures/274x183/3/5/0/1448350_thebrightestsunscreencourtesyhkiff_312678.jpg)

No comments yet