The teams behind Copa 71, Frida, Power and Soundtrack To A Coup D’Etat discuss their creative approaches to using footage.

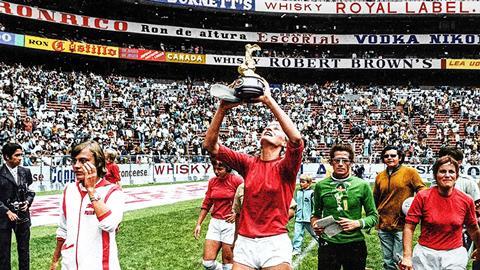

For UK filmmaker Rachel Ramsay, documentary feature Copa 71, about the 1971 Women’s World Cup, started with just 90 seconds of footage from a mislabelled clip found in the Associated Press archives.

“It gives you goosebumps, ‘This is real,’” she recalls. The groundbreaking tournament attracted crowds of more than 100,000 in Mexican stadiums but had been mostly forgotten in sports history – except by the women who played in it.

Those 90 seconds proved, “This event was real, we’re not going mad and the women who remember this are not crazy, and all of the evidence does back it up,” says Ramsay, who directs jointly with James Erskine.

In that clip they could see dozens of cameras filming the action on the pitch, but the surviving footage was hard to track down. At first, people told the filmmakers “it had been lost in a fire, then we were told, ‘No, it had been lost in an earthquake,’” recalls Ramsay, with a laugh.

Their team of researchers (including producer Victoria Gregory, a research veteran herself) found dribs and drabs in various formats over the course of three years – starting on the ground in Mexico, where the matches had been broadcast on local TV. “It was kind of a jigsaw puzzle of building these football matches based on what we had, rather than being able to write exactly what we wanted.”

Compared to the many thousands of hours that a World Cup tournament would generate today, in total the Copa 71 team collected about 20 minutes of video footage of the 1971 Women’s World Cup. One man they found on social media unearthed his grandfather’s old home movies shot from the stands of the stadium.

“It gives it a very different feel and allowed us to be much, much closer in on the action,” says Ramsey. “That was just minutes of footage but it made a huge difference.”

Through creative editing, fresh interviews with the players and other contextual historical footage, they had more than enough to weave together the feature documentary.

“We wanted an audience to feel like they were there,” says Ramsay. “Our stories could carry part of that, but when we could intercut those memories with footage of them as younger players, you can start to recognise them on the pitch and it brings it all to life.”

Archive is not just video. After Ramsay heard from the players that a photographer had been assigned to each national squad, the film team found a “treasure trove” of still images in a vault connected to the University of Mexico City library.

The players’ own scrapbooks and letters could also be corroborated with newspaper articles from 1971. The latter showed the male gaze of the time: shots of the players spending their downtime in bikinis and headlines such as ‘Women’s football is like watching a dog walking on its hind legs: Surprising, but not well done.’”

Ramsay and Erskine’s film has resonated with audiences following its Toronto launch in 2023, especially in the UK and Ireland where Dogwoof’s release in March generated a healthy $187,000 (£148,000) box office. Further validation has come with nominations at the Critics’ Choice Documentary Awards (for best sports documentary) and the British Independent Film Awards (debut documentary director for Ramsay).

Intimate approach

Archive is a vital tool for any filmmaker revisiting a historical subject, and the challenge is to bring the material into the film with creative impact.

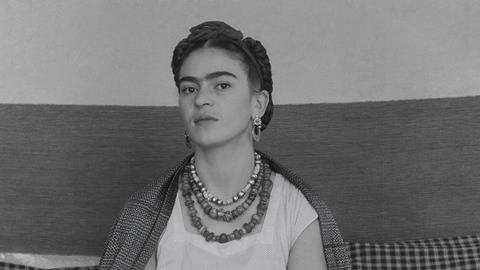

“I always try to make scenes that feel active using archival material,” says director Carla Gutierrez of her Frida Kahlo feature documentary Frida.

“I hate it when people call archival ‘B-roll’. I heard someone recently use the phrase ‘verité archival’, and that is exciting – that’s what I wanted, in finding a way to feel very intimate with Frida. If we want to see the world through her eyes, we can’t just look at photos of her.”

Gutierrez explains it was no easy hunt for moving images of the 1907-born Mexican painter’s life and times, especially to represent her early years.

“We were trying to find 1910s and 1920s archive material in Mexico. I wanted viewers to see through the eyes of this little girl or a teenage Frida. Most of what we initially found would be wide shots with tripods, so we went in search of those old images that might have more fluidity or a lower eyeline,” says Gutierrez, who worked alongside lead archival researcher Manuel Alejandro Martinez Torres and archival producer Adrian Gutierrez and their teams.

Previous Kahlo researchers were helpful to Gutierrez – Hayden Herrera, who wrote a definitive 1983 biography of the artist, let them rummage through her attic. They hoped to find audio tapes of interviews from the 1970s but instead found interview transcripts – still very helpful – and many old newspaper articles.

David and Karen Crommie, a filmmaking couple who made a short film about Kahlo in 1976, shared their valuable audio interviews of people such as the artist’s friends and the nurse who helped her later in life.

“On their dining table they had piles of quarter-inch tapes that had been in a box since the 1970s, that had never been digitised or even touched,” says Gutierrez. “Some of those soundbites appear in our film.”

Gutierrez – a seasoned documentary editor (RBG) making her directing debut with Frida – had the bravery to animate some of Kahlo’s paintings, while also being respectful to the original works and abiding by their legal conditions.

“The art form of film is a different art form,” she says. “I wanted to capture the experience of having that intimacy with the paintings, but in a cinematic space and the paintings needed to become another narrative layer. They needed to move with the storytelling. It needed to emphasise the emotions we were telling in that segment.”

Gutierrez edited Frida herself, and was rewarded with the editing prize for US documentary at Sundance, where the Imagine and Storyville production from Amazon MGM Studios launched, ahead of streaming via Prime Video.

Note perfect

Rik Chaubet’s editing plays a vital creative role in Soundtrack To A Coup D’Etat from Belgian multimedia artist and filmmaker Johan Grimonprez – a film that uses exclusively archival material to tell a rich interweaving of 1960s colonial history, American jazz musicians being sent on goodwill missions to Africa, political unrest in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and the rise of the United Nations.

The film intercuts moments of jazz performance with archive news and home-video footage to tell the story of events leading up to the assassination of Congolese politician and independence leader Patrice Lumumba in 1961. Playful intercuts of commercials for the likes of Apple and Tesla comment on the West’s enduring interest in the Congo’s minerals including uranium and cobalt.

Grimonprez was able to access intimate footage provided by Belgian-Congolese writer In Koli Jean Bofane; an undeveloped reel provided by the daughter of activist and politician Andrée Blouin; and home movies shot by Sergei Khrushchev of his father, Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev, and the latter’s audio diaries.

“We have that personal connection to history, to all these home movies, that makes the story of that history so palpable,” says Grimonprez. “It’s where you feel history is the clash between the intimate story and the bigger world story.”

The film’s global archive team included archival producer Sara Skrodzka and key researchers Judy Aley, Remonde Panis, Pauline Burgaud and Alexander Markov.

The jazz music – from the likes of Dizzy Gillespie, Ornette Coleman and Duke Ellington – bleeds from the performance clips to suffuse the whole film. “We call it jazz interrupters,” says Grimonprez of layering the music over incongruous footage. “It was interesting to have the music sometimes making the commentary” – for example Abbey Lincoln’s screaming on Max Roach’s ‘We Insist!’ playing over footage of a protest at the United Nations Security Council, in outrage at Lumumba’s assassination.

Soundtrack To A Coup D’Etat launched at Sundance, where it received a special jury award for cinematic innovation, and was later acquired by Kino Lorber for North America and Modern Films for the UK release. It earned a Gotham nomination for best documentary feature as well as two European Film Awards nominations.

Getting personal

US documentarian Yance Ford – a 2018 Oscar nominee for doc feature Strong Island – knew he wanted to use archive to build a personal narrative for his Netflix-backed, Sundance-launched Power, which looks at the historic and contemporary abuse of power by police forces. His archivist Jillian Bergman spent over a year doing “more conceptual searches” for the polemical essay film.

“I gave her wide requests like we need representations of police power and we need representations of whiteness,” says Ford.

Power editor Ian Olds adds: “It’s not just creating a structure where you plug in B-roll, we’re trying to figure out what footage has a specific life energy on its own.”

Many of those images could be unlocked in new ways when they were juxtaposed or layered – for example a police training film cut with footage of protests, or a studio test film about policing paired with an interview about the construction of whiteness, or a decades-old instructional training video about chokeholds leading into the story of Eric Garner, who asphyxiated while being restrained by police in 2014.

Ford was interested in “archive as an act of authorship – as we went through the material, you can begin to peel off from the meaning that was in the images, to add on your voice, or your authorship of how you’re putting things next to each other”.

That voice was also added in a literal sense – editor Olds experimented by overlaying a shot of prisoners in staged footage with an outtake of an audio clip from Ford saying, “Okay, we’re ready. Action.” Ford explains: “What Ian constructed has an activation of the past from the present – and there is this relationship between the voice from the present animating the past in a new way. I find that exciting.”

Olds notes that Ford’s voice was crucial. “From the beginning, we were trying to experiment with how this off-camera voice could interrupt the footage to change the narrative, to comment on it, or to take ownership of it. Or we can actually stop the footage and reclaim authorship.”

These filmmakers all agree that archive work is not always easy – there can be fruitless scavenger hunts (Gutierrez found herself calling airlines for reels of film that might have been lost on a plane more than 40 years ago); prohibitively expensive fees from archive houses; footage locked up for media conglomerates’ own use and not available to independent filmmakers; and a wide variety of restoration work needed.

Sometimes the extra digging does turn up those Holy Grails – two of Grimonprez’s favourite finds were footage from AfricaMuseum in Brussels of a crucial roundtable of various Congolese political parties, as well as an audio speech by Patrice Lumumba at the University in Antwerp, which had been presumed lost.

But these films and more show how archive can be a hugely creative tool to tell stories for today’s audiences.

“I think there is a bad reputation that archival has,” says Gutierrez. “But you have to bring an eye to it, to think, ‘How do I create a scene that feels like it’s present day and it feels like there’s action happening?’ You have to bring that together from sources that are scattered and confusing. You can play with it and bring in energy.”

No comments yet